Tyler Technologies: Selling Software to the Government

You can listen to the Deep Dive here

My friend Liberty once mentioned to me that if someone reads William Thorndike’s “The Outsiders”, they should also read Phil Rosenzweig’s “The Halo Effect”. Reading just either, instead of both, of them may run the risk of creating lopsided view of the world of business. Reading both lets you elicit a much more balanced understanding; that’s why Liberty thought that the sum of these two books is greater than the parts!

When I was reading Tyler’s founder Joseph McKinney’s story, it occurred to me that McKinney is one of those rare characters who could perhaps potentially be featured in both “The Outsiders” and “The Halo Effect”. In the first 20 years of Tyler, McKinney seemed like one of those “Outsider” CEOs diligently creating shareholder value by not only operating the business deftly but also using financial engineering with rare dexterity. But then in the next 10 years, things almost completely unraveled at Tyler. Hence, while his glory days can justifiably be celebrated, McKinney is just as equally a cautionary tale.

After graduating from Harvard, McKinney started a Venture Capital firm named Electro-Science Investors in 1960 and became a millionaire after first year of operations. After five years of Electro-Science, McKinney started another company called Saturn Industries which was in the military supplier business. He sold the military supplier business to lessen customer concentration and with the proceeds, he bought a heavy-freight hauler company named C&H Transportation in 1966.

More or less everything McKinney touched turned out to be gold in those early years. C&H turned out to be a success and McKinney seemed to prefer the steady, consistent profit streams of established industrial businesses. Therefore, he went on to buy more industrial businesses; in 1968, he bought Tyler Pipe, a manufacturer of sewage pipes with $43 mn sales. Tyler Pipe became such an outsized contributor to revenue and profits that McKinney decided to name his conglomerate after the namesake.

After Tyler, McKinney bought dozens of other companies, largely funded by bank loans and bonds. By 1975, Tyler became a Fortune 500 company and the company grew its earnings per share by 23% CAGR during the decade of the ‘70s.

In the early ‘80s, McKinney continued his large acquisition spree with Hall-Mark Electronics, a distributor of electronic components, and Reliance Universal, a specialty chemical coatings maker; these two companies contributed 43% of overall sales and 41% of overall profit just two years after the acquisition. While high interest rates and recessions of early ‘80s caused headache for Tyler, it turned out to be just a hiccup for the company.

By the mid ‘80s, Tyler became a diversified conglomerate with three of its six primary business units being the leaders in their respective industries. By 1987, Tyler became one of the largest companies in the US with $1.1 Bn sales and ~10,000 employees.

As the rest of corporate America became more familiar with the “panacea” of acquisition led growth financed by high yield debt, McKinney developed a growing sense of discomfort and decided to go the other way. He decided to divest and liquidate much of Tyler’s assets; by 1990, McKinney sold ~80% of Tyler’s assets and distributed ~$415 Mn cash and stocks back to shareholders. Tyler, however, still had Tyler Pipe as they entered 1990. But by mid-90s, even Tyler Pipe was sold.

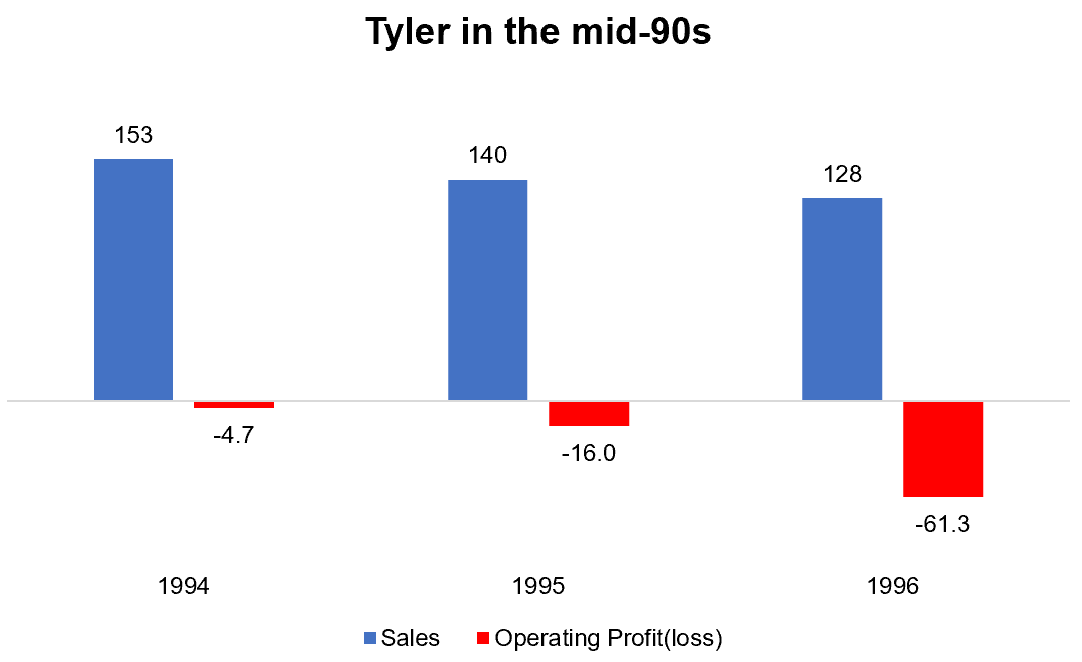

After liquidating supermajority of Tyler’s assets and distributing much of the proceeds back to shareholders, McKinney decided to rebuild Tyler by buying two retail businesses: Forest City Auto Parts (a chain of 61 stores that sold automotive parts and supplies), and Institutional Financing Services (a national education fund-raising services company). Both these companies turned out to be duds, as evidenced by the deteriorating operating performance:

As McKinney’s strategy to reinvent Tyler was clearly failing, he left Tyler in 1996, ending a dramatic rise and fall of the first thirty years of Tyler. A seasoned executive named Bruce Wilkinson then came to lead Tyler. But he didn’t last long as the dispute between Wilkinson and Louis Waters (who owned 10% of Tyler) reached an impasse. Wilkinson wanted Tyler to go back to its roots: industrial businesses whereas Waters wished Tyler to be an information services company. Waters’ wishes prevailed.

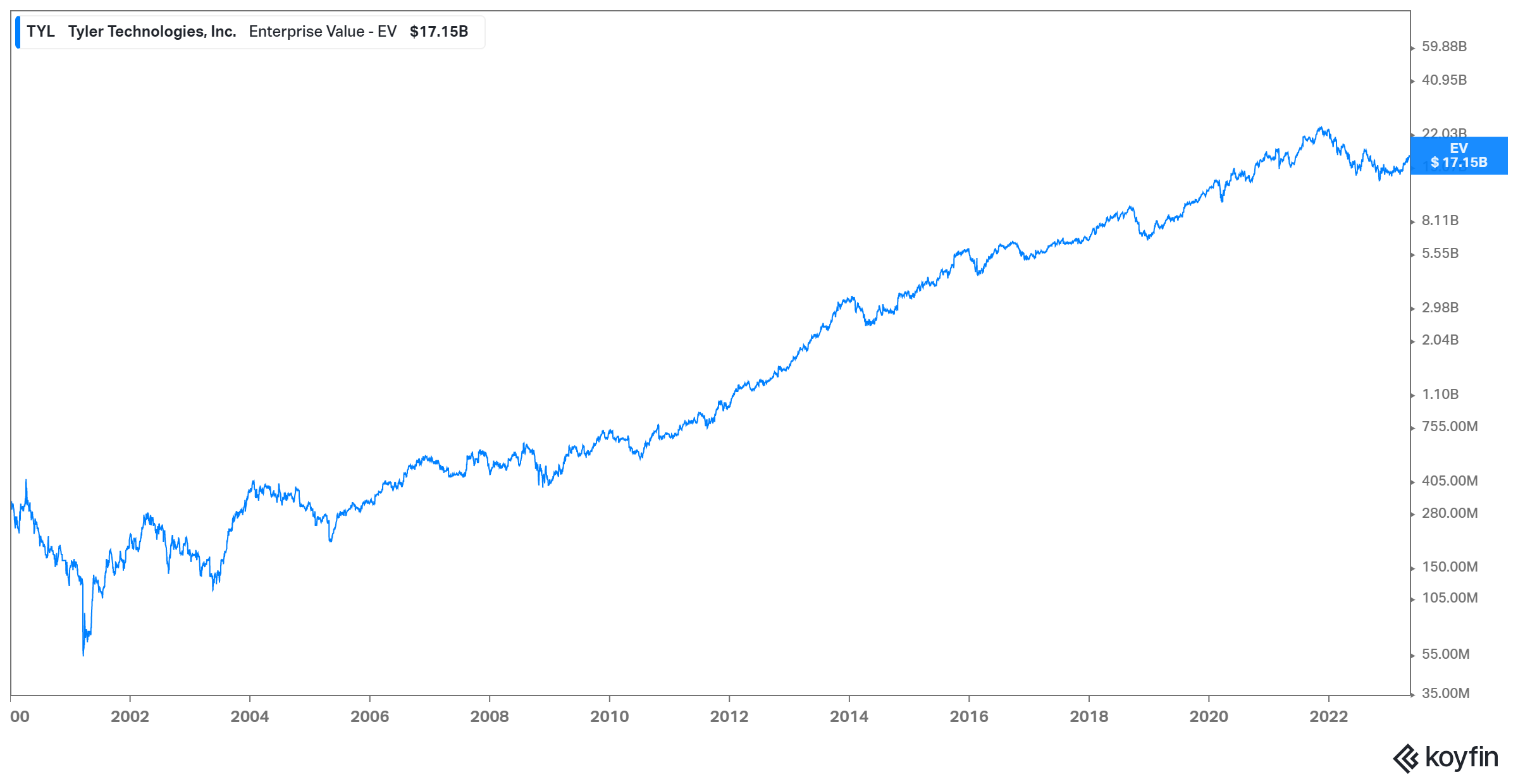

With the acquisitions of Business Resources Corporation, The Software Group Inc., and Interactive Computer Designs, Waters helped Tyler pivot to selling software to the local governments. Waters’ strategy in focusing on providing information services to public sector proved to be a massive success:

Our plan is to consolidate the information industry for local governments. We are looking at smaller counties, municipalities, cities and appraisal districts or police and court systems. They need to computerize their record keeping, dispatch, tax collections, land records, deeds, probation; the possibilities are vast."

While this new strategy had signs of hope, Tyler wasn’t quite out of danger zone for several years. Following the tech bubble, Tyler’s stock also got hammered. In fact, in March 2001, Tyler was trading at only $1.18/share; Lynn Moore, the current CEO and the then in-house legal counsel of Tyler, recalled on a podcast that they were concerned that Tyler might be delisted from NYSE. Back then, Tyler’s Enterprise Value (EV) was just ~$50 Mn; today the stock is trading at ~$400/share with ~$17 Bn EV.

While it was Waters who could be credited for the strategic pivot to selling information services, John Marr almost certainly deserves bulk of the credit for Tyler’s eventual success in selling software to the government. Marr joined Tyler through the 1999 acquisition of Munis where he led the transformation of Munis from a local provider of municipal information systems to a nationwide leader in public sector software. He became COO of Tyler in July 2003 and a year later, he was promoted to CEO. When Marr became CEO, Tyler’s EV was just ~$300 Mn; by the time he transitioned the CEO role to Lynn Moore and became the Executive Chairman in May 2018, Tyler’s EV exceeded $8 Bn.

With this rich historical context in mind (much of which is summarized from here), here’s the outline for this month’s Deep Dive:

Section 1 Tyler’s Operating Segments: I discussed Tyler’s operating segments, business lines within these segments, and NIC, their largest acquisition to date, in this section. The economics of the operating segments are also outlined.

Section 2 The Industry and Competitive Dynamics: Tyler’s addressable market, competitive moats, and current competitors are highlighted here.

Section 3 Management, Capital Allocation, and Incentives: Tyler’s capital allocation history over the last two decades, how it has evolved, and management’s near-term as well as long-term incentive structure are discussed in this section.

Section 4 Valuation and Model Assumptions: Model/implied expectations are analyzed here.

Section 5 Final Words: Concluding remarks on Tyler, and disclosure/discussion of my overall portfolio.