Roku: A former trojan horse now in open fistfight

On an excellent Acquired Podcast, Ho Nam mentioned,“…I call the great serial entrepreneurs just amazing people who just have not yet found their true life's calling. You could be a serial entrepreneur, have a bunch of fantastic hits but then you will find something and say, oh my God, this is it. I found what my life's purpose is. I'm here for the rest of my life.”

After successfully founding multiple companies early in his career, Anthony Wood founded Roku. For almost two decades, he has been committed to Roku. Roku is indeed his “calling”.

The name “Roku” has an interesting story. At a dinner with his wife at a Japanese restaurant, Wood asked the waiter the Japanese word for “Five”. By then, Wood already founded four companies and he was mulling to start the fifth one. When the waiter responded the Japanese word for “Five” is “Go”, Wood did not like the word “Go” as it was also the name of a failed tech company back then. One of the companies Wood founded was SunRize Industries, a software company for Commodore Amiga computer. It employed 14 people making $100k annual profit; despite the success, he decided to close shop to focus on graduating from Texas A&M. After graduation, he moved to California and re-started SunRize Industries. Counting SunRize Industries twice, Wood asked the waiter the Japanese word for “Six”. It was Roku.

For this writeup, I am particularly grateful to two people: Dhaval Kotecha, and a buy-side analyst who prefers to remain anonymous. Dhaval works at ad tech industry and the analyst has followed Roku for a while. I had two lengthy discussions on Roku with them. Those discussions made this deep dive richer than it would otherwise be. As my primary objective is to understand the company as well as perspectives of both bulls and bears, interactions such as these have become an integral part of my research process.

Here is the outline for this month’s deep dive:

Section 1 Roku Business Model: I explained how Roku makes money, especially its monetization of platform segment.

Section 2 Roku’s Trojan Horse Strategy and KPIs: Roku’s position in the broader media ecosystem (TV OEMs, Retailers, Content publishers) as well as the KPIs (number of active accounts, streaming hours, and ARPU) it closely tracks are highlighted in this section.

Section 3 The Bull/Bear Debate: Roku mentions four key areas of investment: advertising, The Roku Channel, Roku TV, and international markets. I have discussed what bulls and bears think on these key focus areas.

Section 4 Valuation and Model Assumptions: Model/implied expectations are discussed here.

Section 5 Management and Incentives: I opined on the management, potential succession plan for Anthony Wood, and management incentives.

Section 6 Final Words: Concluding remarks on Roku, and brief discussion on my overall portfolio.

Section 1: Roku Business Model

Anthony Wood was already wealthy when he founded Roku in 2002. He sold iBand in 1996 for $36 mn and ReplayTV in 2001 for $42 mn.

Initially, Roku had developed internet radios, high-definition media players, and digital signage business which was later spun out to be an independent company called BrightSign in which Wood continues to be the Chairman of the board.

After getting some traction on Roku’s initial products, Wood explored the opportunity to work with Netflix to develop a streaming player. Netflix was a bit hesitant. But when Netflix started doing a search for VP of Internet TV, Wood joined Netflix and started building The Netflix Player, which is “a black and boxy device, as plain and compact as a necklace case, which subscribers would hook up to their televisions to stream movies and TV shows from the web.” Netflix was *this* close to go to market with the hardware, but at the very last moment, Reed Hastings became wary about potential conflict of interest between licensing others content and selling hardware simultaneously. This alleged Hastings’ quote perfectly encapsulates his dilemma,

“I want to be able to call Steve Jobs and talk to him about putting Netflix on Apple TV but if I’m making my own hardware, Steve’s not going to take my call.”

Eventually, Netflix spun out Roku and let them be an independent company. Netflix then sold its shares to Menlo Ventures in 2009 and made $1.7 mn gain on $6 mn investment. For the sake of brevity, I am skipping the details here, but this Fast Company piece on Netflix-Roku saga provides intriguing background to the whole saga.

Today, Roku, an independent company trading on NASDAQ as ROKU, reports its revenue in two segments: Player revenue, and Platform revenue. Let me begin by explaining these segments first.

Player revenue: Roku sells its streaming players through consumer retail distribution channels. In its 10-k, Roku identifies Customer A, B, and C contributing 10%, 18%, and 40% of the player segment revenue. I am assuming these are Best Buy, Amazon, and Walmart respectively (one of them could be Costco too). In international markets (Canada, UK, France, Ireland, Mexico, Brazil, and some other LATAM countries), Roku sells its players to wholesale distributors who then sell it to retailers in those countries. Once you buy a Roku stick, you can plug into your “unsmart” TV to convert it to smart TV.

If you are not familiar with Roku’s streaming players, you can explore their products here. Audio products such as wireless speakers, smart soundbars, and wireless subwoofers are also included in this segment.

While Roku sells hardware in the form of streaming players, it is anything but a hardware company. The hardware is essentially the trojan horse that most investors and industry insiders had hard time discerning. Wood bootstrapped Roku in the initial years, and when he wanted to raise venture money, investors were very skeptical since all they mostly saw was hardware revenue, even though the Roku pitch from its inception was that they are going to make most of their money on platform services.

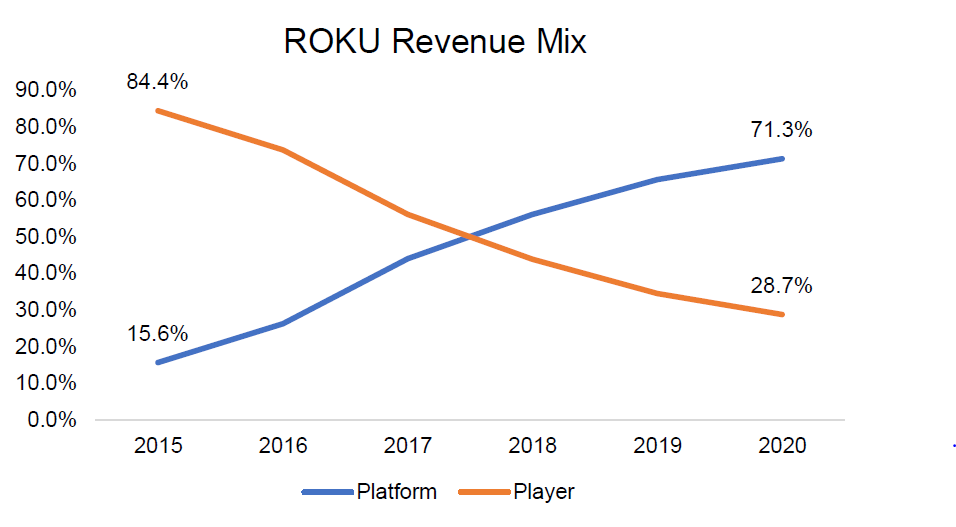

This lack of imagination from the investors is not hard to understand as up until in 2015 player revenue was ~85% of total revenue. Just in 5 years, this revenue has come down to less than 30%. I believe player revenue in the overall revenue mix will be in high single digit by 2030.

Even though player revenue is losing its significance in terms of numbers, it remains a key distribution advantage. It enables Roku to generate platform revenue. Given this strategic importance, Roku is willing to sell hardware at a low profit margin. Gross margin on players fell from mid-to-high teens in 2015-16 to mid-to-high single digits in the last two years.

I do want to mention here that if you buy a Roku branded TV, that’s NOT included in the player segment revenue. Roku just licenses its technology to Smart TV OEMs. This licensing revenue is included in the platform revenue. The real business of Roku is to become the Operating System (OS) of the modern TV ecosystem.

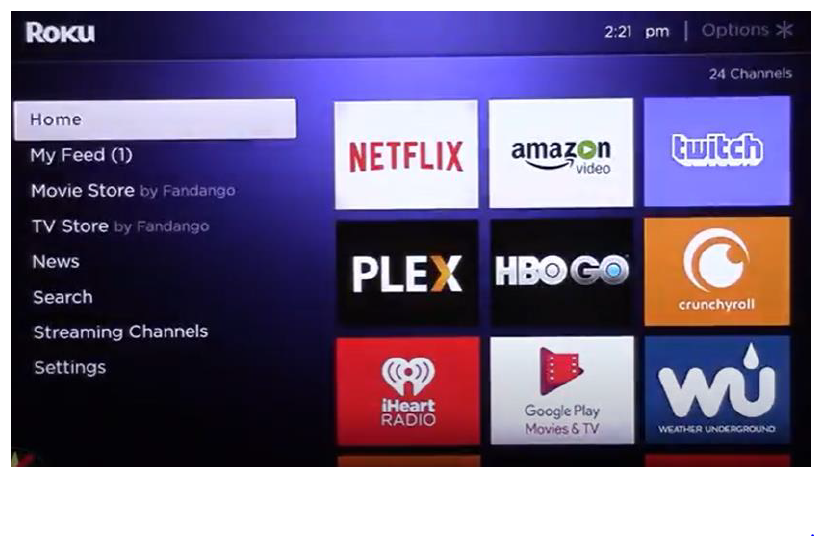

Platform revenue: After you buy the Roku stick or a Roku branded TV, something like the screenshot shown below appears once you launch your TV/stick. You are now on Roku’s “platform”.

Before I explain Roku’s platform revenue segment, I will very briefly touch upon some jargon for the sake of clarity. Roku is a primary beneficiary of cord cutting as TV audience has increasingly been moving to streaming or Over-The-Top (OTT). This bypasses traditional distribution channels such as cable, satellite, and broadcast and delivers content directly via internet. Within the OTT ecosystem, there are generally three monetization methods:

a) Streaming Video-on-Demand (SVOD) lets users subscribe to a library full of content that they can watch anytime the user chooses.

b) Transaction Video-on-Demand (TVOD) allows the user to rent/purchase content at a one-off fixed price, and

c) Ad supported Video-on-Demand (AVOD) lets the user watch content for free or at reduced price relative to SVOD. For that privilege, the content may be interrupted by ads.

There are multiple ways Roku monetizes its platform. Let me elaborate Roku’s monetization methods below.

If you are SVOD consumer but haven’t sign up for the subscription, you can subscribe from Roku’s platform. Roku typically receives ~15-30% cut of the subscription. Although Roku does not disclose the percentage explicitly, it is fair to assume that the cut depends on Roku’s negotiating leverage with the content publisher. If it is Netflix, it may be 15% (or even less?). Important to note here that Roku receives the cut as long as the subscription remains active. It is a recurring revenue. However, if the user is already a subscriber, Roku does not receive anything from the subscription fees.

In addition, Roku monetizes from users purchasing one-off content. 20-30% of the TVOD transaction fees are captured by Roku when the purchase of content from the content publisher happens on Roku.

Furthermore, Roku also allows the placement of a branded button on its remote (shown below). Roku charges $1 per branded button per remote to content publishers. Recent remotes include Apple TV and you can also customize the “1” and “2” button on the remote to any channel you want.

Finally, Roku also has an AVOD business. In fact, majority of platform revenue comes from advertising. Roku generates revenues from AVODs such as Pluto and Tubi through ad inventory split or sales representation program (discussed below).

Roku also has its own AVOD channel: The Roku Channel (TRC) which any Roku customer can access for free. Roku licenses content from 175+ different companies for TRC. Roku also has started acquiring content outright (e.g. Quibi, and This Old House). While Roku can generate more revenue if viewers spend more time on TRC, this is lower gross margin business since Roku typically has 50-50 revenue share with the content owners. On the other hand, if viewers spend more hours on other AVOD channels, Roku generates lower topline, but that revenue comes at a very high gross margin.

The ad load in AVOD varies by content publisher. Roku mentions that an hour of TV on most networks comes with ~16 minutes of commercials while TRC shows only 8 minutes of ads. These ads could be either brand advertising or content studio ads (highlighting other content by the same publisher).

How does Roku monetize this? Dhaval Kotecha, who works at Programmatic AdTech industry, recently explained Roku’s AVOD monetization in an illustrative tweet (shown below).

Roku has also been recently highlighting the potential of performance marketing via Roku platform. In the recent earnings call, Roku mentioned the following:

“I’d offer up an example with Home Chef, a very performance-based advertiser, who invested with us and saw 2.4x return on ad spend and then came back and significantly invested more with us. And we have case studies like that left and right. It’s really a unique attribute of streaming that can both compete at a top of funnel – as a top of funnel branding medium as well as a mid- and bottom funnel performance medium.

…Our product remains a premium product. If anything, we’ve added better data, better targeting, better measurement, newer ad products over time. And I think that, that bodes well for continuing to be able to command premium CPMs. But I will also call out to the earlier question from Ralph that streaming is increasingly also a performance media. And the reason I call that out is because advertisers will increasingly be looking not just at the top line CPM that they buy the media at, but the effective cost per whatever, cost per site visit, cost per product purchase.

And what that means long term is that unlike traditional TV, streaming CPMs aren’t just going to be sort of a “one price rules them all” type scenario, but rather a whole spectrum of prices where the pricing into the auction is ultimately dictated by the tactic that the advertiser is executing on and the outcome that they’re trying to drive”

To further its ambition in this direction, Roku acquired Nielsen’s Advanced Video Advertising (AVA) business in March 2021. This includes Nielsen’s video automatic content recognition (ACR) and dynamic ad insertion (DAI) technologies. With ACR, marketers can get useful insights and information about who is watching what content and when. If you are watching 'How clean is your house?' on your Smart TV, ACR technology could serve you with an ad for the latest vacuum cleaners. With DAI, advertisers could reach across platforms: both linear and VOD to stitch custom targeted video ads into the stream, based on the individual user viewing the content.

In the recent call, one sell-side analyst asked what the mix of these advertising monetization methods (brand advertising, performance ads, content studio ads, and DAI/ACR) will be a few years from now. Roku responded, “…frankly, we’re not sure, but we are sure that those segments are quite substantial, each of them on their own.”

Beyond ads, Roku also licenses its OS to TV OEMs. From speaking with people in the ad tech industry as well as several investors, I am reasonably confident that OEMs pay little to no money to Roku to license Roku’s OS. If anything, there is debate in the industry whether Roku should pay to these OEMs since being the OS is much more lucrative than being an OEM.

There are also a few other ways Roku monetizes its platform such as channel development modes and billing services, but I am skipping these here. You can explore more of those here.

Given the different sources of revenue in platform segment, it would be helpful to get a sense of revenue mix within the platform segment. Unfortunately, the best information about the mix I could find is from the Citi Technology Conference held in September 2018. Then, two-third of platform revenue was ad related and one-third was content distribution (sign ups, services etc.). Within the ad business, majority of it was video advertising i.e. 15-30 second spots. The business has certainly changed a lot since then and ad revenue could be more outsized in contribution today than it was in 2018 as many of the current advertising tools were only launched recently (TRC itself was launched in late 2017). The fact that platform gross margin declined from 71.1% in 2018 to 60.3% in 2020 implies contribution from ads increased as non-ad platform revenues are higher margin business. For context, if ads drove ~80% of platform revenue in 2020, that implies 57% of overall revenue. Going forward, this contribution is likely to increase even further.

In its 10-K, Roku mentioned “Customer H” contributed 13% of total platform revenue (or $165 Mn) in 2020. I do not know who customer H is, but when I posed this question on twitter, some said the answer is TCL or a TV OEM. That is almost certainly the wrong answer. The most likely answer is Disney since they launched Disney+ recently and they have multiple AVOD properties on Roku platform.

To summarize, even though the business model seems very complicated, Roku’s monetization is primarily from advertisements. Every time you use your Roku TV, you are on Roku’s platform and Roku’s monetization is largely reliant upon how long you are watching your TV via Roku’s platform.

Section 2: Roku’s Trojan Horse Strategy and KPIs

There are a number of players in the media ecosystem. For a long time, Roku was able to convince everyone in this ecosystem that Roku is an agnostic platform helping everyone in the ecosystem reach their customers. Anthony Wood devised some strategic masterstrokes to help Roku reach where it is today.

In the initial years, Roku had a box that customers had to buy, and in 2012, they launched the Roku stick. There were three separate challenges with this hardware strategy: you need to convince the customer they should buy the box/stick, they should choose your box over competitors, and finally, once they buy it, they should use it. When Smart TV came to the scene, Roku finally found a far more potent and effective strategy: they started licensing their OS to TV OEMs. Once you are the OS of the TV, you don’t need to do any more convincing. All the three challenges merged to just one: just convince the customer to buy Roku-branded TV. While 57% of the TVs were Connected TV (CTV) in 2015, CTV’s penetration rose to 80% in 2020. Once a customer buys Roku branded CTV, Roku can enjoy the power of being default.

So, how did Roku convince the TV OEMs to license Roku OS on their TVs? What role did Roku then play to convince retailers to sell those TVs? And how did they partner with content publishers? Let’s go over each of these questions.

OEM: Historically, TV manufacturers were American companies such as RCA and Zenith. Then Japanese OEMs such as Sony and Panasonic dominated which was followed by Korean companies such as Samsung and LG. However, when Roku was pondering with whom to partner, they decided to go with Chinese TV OEMs for two reasons: a) Roku thought Chinese manufacturers were vertically integrated and could control the cost of manufacturing which is of paramount importance since TV OEMs is a very thin margin (~1-2% operating margin) business, and b) dominant players such as Samsung weren’t quite enthusiastic to partner with Roku. Given the anemic market share of Chinese OEMs in the US, Roku thought they would be the most willing to work with Roku. So, Roku made this calculated bet and partnered with TCL in early 2014. TCL was practically unknown brand in the US and ranked 24th in terms of market share in the US. Today, TCL has the third highest market share in the US. I will explain shortly how this transformation could possibly happen.

Roku currently licenses its OS to total 15 OEMs to sell Roku branded TVs. The strategic masterstroke was NOT to have an exclusive partnership but building on success of one OEM brand and then commoditize the OEM by partnering with multiple other OEMs over the years. The OS of the TV is likely to be more durable than any particular TV OEM.

Retailers: As indicated earlier, TV OEM is a commoditized business. TCL’s ~15-20% gross margin and ~1-2% operating margin also hint at that reality. One of the most powerful players in the TV OEM ecosystem is the retailers such as Walmart and Best Buy. Walmart can decide to keep just a handful of brands in their store and decide the fate for OEMs depending on who gets picked. Since TV’s features are hardly differentiated, one of the most differentiating factors to be picked is price. Anthony Wood explained these dynamics in an interview:

“…our software runs on low-cost TVs, it costs less to build a TV with Roku software. When you’re trying to get 50 cents off your bill of materials so you can win a Black Friday special at Walmart, the amount of money you save by cutting your RAM in half and your CPU in half by running Roku software — which actually has great performance and more content — is huge. It’s the difference between getting distribution and not getting distribution in Walmart.”

So, once TCL got picked by the retailers because of its attractive price point, it quickly moved through the ranks to become one of the top TV brands in the US.

Content Publishers: Content publishers are perhaps the most important constituent in the media ecosystem. Given Roku’s identity as platform, Roku insisted on portraying itself as agnostic to any particular player in the broader ecosystem. Wood explained the strategy in an interview:

“In our early days we used to avoid talking about cable, cutting the cord and stuff because we didn’t want to annoy our partners, but I think one of our goals is to be a good partner. A good partner for our TV partners, good partner for our retailers, good partner for our content partners, and we have MVPDs that are good partners as well. We have the Xfinity App on Roku. We distribute, like you said, we distribute streaming players through DirecTV, AT&T stores, through Sling, which is owned by Dish. So I would say that the answer is we try and be a good partner. For a long time they resisted the trend, but I think now most companies realize people are moving to internet for TV and they need to embrace that. So we wanna help them.”

However, this agnostic image has recently been changing. Given the rise of OTT offerings, it is hard to remember which OTT platform has what shows, and of course, it is not cheap to subscribe to ten different streaming channels. While customers are on Roku’s platform when they buy Roku branded TV or stick, Roku understood the value of content. Customers have affinity with the content, not the OS. Roku probably thought what got them from “1 to 10” may not take them from “10 to 100”. As a result, TRC was launched. TRC is currently following the Netflix’s initial OTT strategy by licensing content from others and opportunistically outright acquiring content at times, but the end-game is hardly agnostic, and strongly Roku-centric:

We do think the future is a different UI, which is more content-focused. More recommendation-focused. And we have that UI! It’s called the Roku Channel… The Roku Channel is our sort of sandbox for building a next-generation, content-first user interface. And someday, when we think it’s ready and good enough and has enough content in it, it’ll probably become the home screen: Anthony Wood

As you can gauge, Roku is part of a complex media ecosystem. To simplify this apparent complexity, Roku has outlined three Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to track its progress: a) Number of active accounts, b) Streaming Hours, and c) Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) on its platform.

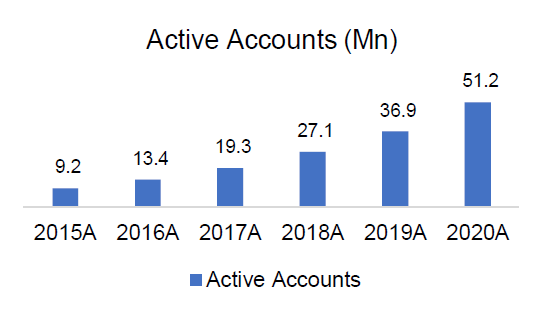

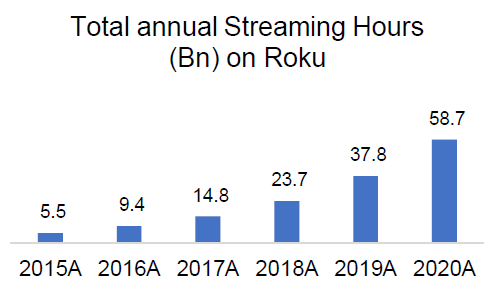

Number of Accounts: This particular KPI tracks the scale of Roku’s platform. Since monetization of a user only begins when he/she has the Roku stick or Roku branded TV, Roku is, first and foremost, focused in growing the scale of its platform. They were willing to drive down gross margin by ~1,000 bps to grow active accounts at 41% CAGR over the last five years.

Streaming Hours: Once customers have the TV/stick, the next level of KPI is the engagement of the customer in the Roku OS. Roku is founded on the belief that “all TV content will be streamed”. However, creating engaging content is not child’s play and require a lot of capital to produce on a consistent basis. As Buffett said, “the best business is a royalty on the growth of others”, Roku immensely benefited not by producing capital intensive engaging content for consumers, but distributing such content, and then monetizing the streaming hours of consumers through superior ads than linear TV. Streaming Hours on Roku grew at CAGR of 60.6% in the last five years.

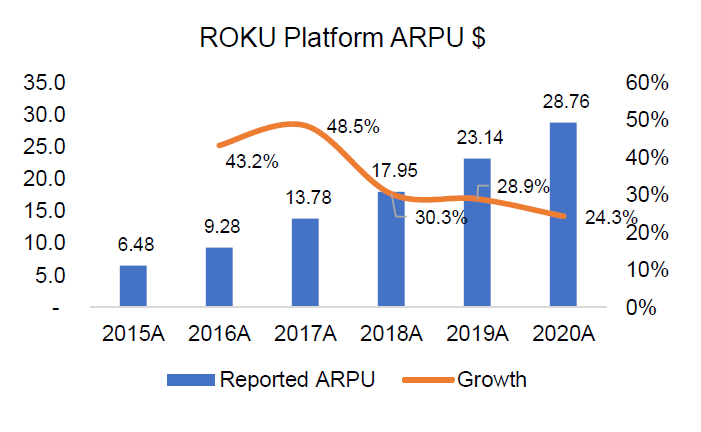

ARPU: If customers buy the stick/TV and watch engaging content on Roku’s OS, the final KPI corresponds to how well Roku is being able to monetize this engagement. ARPU is basically the total platform revenue divided by the average number of users in a period. The trove of data Roku’s platform has on consumers helped them increase ARPU at 34.7% CAGR over the last five years. ARPU is a testament to the effectiveness of Roku’s monetization methods and it is apparent that once active accounts scale and consumers engage by streaming content, Roku knows how to monetize such engagement in a very effective manner.

Section 3: The Bull/Bear Debate

Roku highlights four key investment areas in its business: advertising, TRC, Roku TV, and international markets. I will focus the bull/bear debates on these four key themes. My objective is to avoid strawman arguments on both sides. I will keep this section largely qualitative but will tie many of these bull/bear arguments when I discuss the model assumptions in Section 4.

Advertising

While consumers streamed 58.7 Bn hours in aggregate on Roku’s platform, a large percentage of this is SVOD, especially Netflix. Roku mentioned in their S-1 in 2017 that Netflix alone contributed one-third of the streaming hours and the top five streaming channels contributed 70% to the total streaming hours. Since then, Roku stopped publishing these numbers in their 10-k or earnings calls. It’s important to note that despite Netflix and YouTube’s outsized contribution (likely still >40% of total streaming hours on Roku’s platform), Roku makes negligible money from Netflix (only if you signup on Netflix via Roku) and YouTube (S-1 mentioned “no revenue” from YouTube). Basically any SVOD streaming hours (likely two-third of total streaming hours) are not monetizable by Roku apart from the cut on recurring subscription revenue if signed up via Roku.

Roku believes even though more and more companies are offering SVOD, most of them are doomed to fail and will eventually shift their focus to AVOD which is good news for Roku’s monetization. SVOD is a scale business; it costs same amount of money to produce “Game of Thrones” regardless of who is producing it, but the size of your subscriber base you can amortize the costs over a period of time varies which is the primary determinant of the eventual competitive advantage in the SVOD world. Therefore, it is highly likely that there will be a handful of winners in the SVOD and the rest will either be bundled SVOD or just be just shifted to AVOD. AVOD’s increasing penetration would be great news for Roku as it will increase their ad inventory and monetization capabilities. Here’s how Wood expanded on this in an interview:

“…why do people cut the cord? They cut the cord for two reasons. One is they cut it because it’s a better experience streaming. There’s tons of content. You can pay for just what you want to pay for, it’s on-demand, so much better experience. They cut the cord to save money, as well.

We don’t think people want to replicate their large cable bundle costs in the streaming world, so we think what’ll happen is, and what we see, is that consumers will sign up for a small number of SVOD services, Netflix, maybe one or two others, but then they want to supplement that with a lot of free content. Probably the No. 1 question we get in search on roku.com for pre-sales is, “What can I get on Roku for free?”

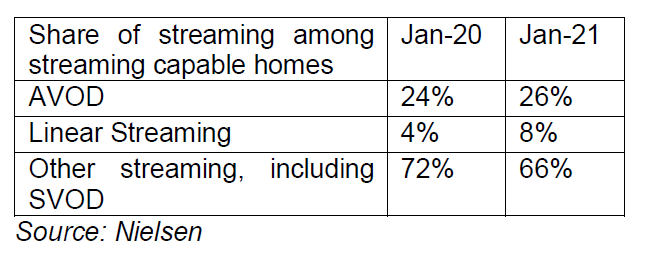

While Roku doesn’t quite disclose TRC’s streaming hours, it did mention that TRC is the fastest growing channel on Roku. I do wonder though whether this is just mere base effect. But the thesis on rising AVOD penetration does seem to be right. As per Nielsen’s data, both AVOD and linear streaming penetration in overall streaming is rising. In fact, non-SVOD penetration within streaming is rising faster in certain demography. For example, 45% of the total streaming hours in African American households came from non-SVOD channels. Streaming itself is accounted for 25-30% of all TV viewed in the US. Therefore, as cord cutting continues and streaming continues its secular journey, Roku will enjoy a tailwind. On top of it, AVOD’s rising penetration within OTT should provide them further momentum.

The TAM for TV advertising is $173 Bn, of which $70.6 Bn is in the US. As the gatekeeper of OTT content, Roku is in an enviable position to capitalize on this big market as TV watching hours shift from linear to OTT. Roku’s recent acquisitions such as dataxu in 2019 which is a Demand Side Platform (DSP), and Nielsen’s Advanced Video Ad business in March 2021 clearly indicate Roku’s broader ambition in the ad business.

The shift from linear TV to AVOD is fundamentally order of magnitude better from advertisers’ perspective. The depth of first-party data that Roku has is almost unimaginable in the traditional linear TV ad business which makes it intuitive that the TAM for CTV advertising can possibly be larger. As mentioned in section 1, Roku does highlight the potential of DAI/ACR and performance marketing in the CTV world.

The breadth of data Roku has was mentioned by a recent expert call transcript I read:

“I'm literally looking at a spreadsheet right now where we have something like 400 different audiences. There is like whiskey drinkers, people who have a high propensity to potentially be diabetic, just all that data that you have access to through digital.”-Former Roku employee

Trade Desk in 1Q’21 call also indicated how big the CTV ad market is:

“…according to Omdia's latest research, there are now more than 200 million active AVOD users in the U.S. alone. By 2024, Omdia predicts that annual CTV advertising revenue will top $120 billion, outperforming subscription revenue by more than 20%. Omdia also predicts that markets such as the U.K. and Germany will be the fastest-growing CTV markets outside of the United States, driven by very similar consumer shifts. These trends are very consistent with what we're seeing, and that's why we're investing so heavily in CTV.”

While I agree that compared to the potential for CTV’s ad TAM, we are still in the early stage, there are some nuances that I believe go missing in some bullish arguments. For example, Roku in JP Morgan Technology conference (24 May, 2021) mentioned that while streaming hours is one-third of total TV watching hours, only ~10% of ad dollars shifted to CTV, and hence, advertisers will inevitably follow the eyeballs and this discrepancy won’t sustain.

I agree there is discrepancy between eyeballs and advertising dollar, but it is lot less than the aforementioned data suggests since two-third of OTT is SVOD and hence mostly beyond the scope of advertising. However, given SVOD’s current dominance, it is possible the nature of advertising itself may change going forward. For example, SVODs such as Netflix may never show ads during the shows, but it is highly likely that their content will integrate brands in the future which will serve two compelling purposes: a) viewers don’t get annoyed with ads during watching shows, and b) the line between content and ads gets completely blurred which is perhaps any advertiser’s wet dream. Let me explain what I am talking about by quoting Nielsen’s recent “Total Audience Report”:

“Nielsen recently analyzed the viewership of Cobra Kai to assess the equivalized value of the branded integrations within the first four weeks the program was available to stream… Enterprise is one of the brands that Cobra Kai weaves into the storyline. And in the first four weeks of being available on Netflix, seasons 1/2 of Cobra Kai delivered Enterprise more than 8 million impressions to viewers 21+, a key age demo for car renters.”

Modern ads may eventually not look like the ads we have seen in the past. You and I can watch the same show and the protagonists can have a conversation in front of grocery shop, but you may see Sainsbury’s if you are in London, and I will see Loblaws since I am in Ottawa. It is important to note that these types of ads can be integrated both in AVOD and SVOD without degrading customer experience at all. Although I do not know to what extent Netflix is already implementing this, I think almost all SVODs, including Netflix are extremely likely to warm up to these extremely high margin ad dollars. To get a sense of how modern ads look like, I encourage you to explore here. If these types of ads become a larger part of the future advertising budgets, it may also make SVODs very cost competitive for consumers. Most Netflix bulls assume Netflix has pricing power and they will exercise that power with time. But if Netflix can start generating ad dollars without degrading customer experience, SVOD can maintain the pricing competitiveness and may continue to dominate the streaming hour penetration for years to come.

How about the potential for performance marketing in CTV? While most people either cannot or probably do not want to click ads on a TV which make it somewhat less appealing from performance marketing perspective, it is true that when advertisers just want to create brand awareness, an ad on a big screen is much more compelling than it is on a mobile/tablet. As a result, while CPM on mobile typically hovers between $0.5-1.5, CPM on TV is $15-20.

Moreover, Roku’s Trojan Horse strategy with content publishers is in a really interesting and tight spot at the moment, a discussion that I came across after going through some expert calls. For most of Roku’s history, they did a lot of custom deals with almost everyone. To entice a content publisher, Roku would go to them and offer them 85-90% of the ad inventory and keep the rest 10-15% to themselves. Roku’s whole focus was just to get everyone on their ad platform. The economics of such deals made ton of sense to content publishers, so they all signed up. However, once Roku started to gain scale and renewal of the deal came up, Roku wanted to reinstate the standard split (30% Roku and 70% content publishers) of the ad inventory which created a lot of disputes between Roku and others. Obviously, in such case the economics for the content publishers is not as attractive as it was before.

Now that Roku has >50 mn active accounts and perhaps ~100 mn audience on its platform, it has almost entirely stopped doing those custom deals. Roku clearly thinks it has the leverage now and they are probably right on this when it comes to most of the content publishers.

Owning the platform has tremendous advantages and it is difficult to predict the full range of monetization capabilities of Roku in the next 5-10 years if they can protect their gatekeeper status. For example, when you launch your Roku OS, you may see “Paramount Pictures” in the homepage for which Paramount would pay a lot of dollar for that privilege. If Roku’s platform continues to scale, the value to be on its homepage will increase even more. This is, of course, a very high margin revenue stream. The bulls I spoke with seem very excited with recent Nielsen video unit acquisition as well. Some even think that it is likely that following the recent acquisition, Roku probably has a very holistic data from the entire media ecosystem which may allow them to help advertisers even run ads on linear TV.

It is worth mentioning that barring Netflix, nobody in the OTT content business actually makes money which makes Roku’s hardline strategy particularly precarious for content publishers. Even Netflix posted positive FCF for the first time during the pandemic and was posting negative FCF prior to that. If content really is the king, it is an open question to what extent the broader ecosystem will allow Roku to gobble much of the profit. If top 5 SVODs can continue to generate more than half of the streaming hours 5-10 years from now, the mudslinging disputes about ad inventory splits can turn uglier as Roku may demand even higher share from the AVOD services.

The Roku Channel

Before I talk about The Roku Channel (TRC), I want to first give you a better context to the content vs distribution debate. Roku bears seem to be ardent students on the history of the media ecosystem and how the pendulum had swung between content owners and distributors. Bears believe in the age of internet, distribution won’t have much leverage and much of the profit pool from the media ecosystem will largely reside on content owners’ financial statements.

To understand the context of bears’ concerns, let me provide you a bit more background where they are coming from by elaborating on the history of this pendulum swing between distributors and content owners.

In the early 1940s, ABC, CBS, and NBC launched free ad-supported content to any home within the reach of a broadcast tower. With the help of coaxial cables across the US, the reach of the broadcast networks went beyond the tower’s signal range. In early 1970s, Ted Turner created the first cable network which allowed consumers watch TV network outside their local market. Then came TCI’s John Malone who expanded and acquired for 20 years to piece together the largest cable system in the US.

From ’70s to ‘90s, the Ted Turners of the world desperately needed broad distribution on the cable system. Because of the leverage, TCIs of the world could get a nice deal in their favor for giving network operators the privilege to access their distribution. The content owners not only offered carriage fees but also offered equity stake at times to distributors. Distribution was the clear winner in this era.

Since late 90s, the pendulum started to move to content owners for two reasons: a) since content owners received wide distribution and created a loyal audience, they started investing expensive programs such as sports, and b) Dish and Direc-TV’s satellite pay-TV services encroached the “monopoly” of distribution of cable systems. Both these dynamics swung the balance of leverage in the relationship between content owners and distributors. As long as customers really want to watch your content, the winner in the negotiating table was almost decided even before the discussion could begin.

Content networks with must-have content such as ESPN could gradually raise fees to distributors over the last two decades. Even though it led to a lot of disputes and a lot of empty threat from distributors, ultimately the cream of the economics was enjoyed by content owners. As a result, while video margins for cable and satellite distributors were approaching zero, content networks were able to build 40-50% margins by mid-2010s.

Today, we are now in the brave new DTC world in which every line/identity is getting increasingly blurred. While TV watching hours is shifting from linear TV to OTT, 70% of Netflix streaming hours is still watched on TV. So, the real debate and question is whether OS of the smart TV (Roku and other TV tech platforms) has any leverage over content owners.

Bears think over time DTC will be winners-take-most and with just handful of winners, they will be able to build strong connection with the audience which will give them incredible leverage in any dispute with platforms. Tech platforms may end up being just commodities and can be hard fought with other big tech companies (Google and Amazon specifically) and therefore, they won’t quite enjoy juicy economics that bulls think they will over the long term. (Note: many of these historical details are summarized from this excellent substack)

For what it’s worth, it seems to me that Roku perhaps has some sympathy to this argument. TRC was launched in September 2017 and was basically run by licensing from 175+ content partnerships at 50-50 revenue share. TRC’s content library includes 40k+ free movies, TV programs, and 190+ linear TV channels. Roku likes to mention how TRC creates a flywheel, as repeated in the most recent call by Wood:

“there's this virtuous cycle where more consumers coming into TRC, more viewers is increasing our ad revenue, which is allowing us to spend more on content, which is driving that flywheel. Some examples, both reach and engagement, streaming hours grew more than twice as fast as the platform overall, which is growing fast than last quarter.”

A common retort from bears about TRC is “I don’t know anyone who watches TRC” which I find quite a suspect argument as it reminds me of the common rhetoric of “nobody uses Facebook”. The super majority of investors are wealthy people and frankly speaking, they (and their friends) lead too interesting lives to watch second-tier free content on TRC, but they may not be representative of the broader population. I wish Roku disclosed TRC’s streaming hours separately instead of just alluding to this unspecified “faster” growth in earnings calls.

On May 20, 2021, Roku debuted 30 “Roku Originals”, which are content acquired from Quibi along with content developed or acquired by Roku in the future. Roku now expects to release another 45 “Roku Originals” this year. In a recent blog post, Roku updated how their originals are doing: “In the two weeks following the launch of Roku Originals, May 20 to June 3, a record number of unique accounts streamed The Roku Channel. Furthermore, the top ten most watched programs on The Roku Channel were all Roku Originals in this two-week period.”

As much as Roku wants me to get excited reading this, it doesn’t quite tell me the full picture. More numbers such as number of accounts streaming TRC or streaming hours would be far more helpful.

On June 03, 2021, Roku introduced “Roku Recommends”, which airs every Thursday, and the hosts highlight Top 5 movie and television recommendations for the week. This is a genuine pain point for consumers as I am sure almost all of us googled at some point what to watch. I, however, don’t expect these recommendations to be actually impartial, and this may be another way to prop up TRC’s status in the deluge of content.

Bulls argue given the first-party data points Roku has, Roku has much better ability to predict what sort of content to license/acquire from content publishers and once they reach better scale in terms of streaming hours, they will be able to license/acquire better content (and the flywheel will keep spinning). The content is, bulls believe, the final nail in the coffin. Once Roku reaches the scale, it is almost game over for many sub-scaled content publishers as they would be tempted to license content to Roku who would have higher distribution with more ways to promote content to watch.

Why don’t bears quite buy this argument? They basically think it’s going to be lot more treacherous path as scaling content is not a child’s play. It is perhaps much more plausible to imagine Amazon Prime (and MGM) or even Google to ramp up their content investments before Roku can get there. As I was listening to an expert call recently, I found some sympathy to this argument from a former Roku employee:

“A platform company making money almost entirely off of advertising and subscription-based models, recurring revenue monthly off of users. That's what they're doing now instead of just selling boxes. Now, when you get into the content game, there's a couple of things. One is the money that it takes to actually do this content is incredible. It's way out there. For Roku, you're talking about a company that has really only turned a profit every couple of fluke quarters because of various wins. They're taking that money in reinvesting into advertising technology.”

Roku TV

As indicated earlier, some Roku bears think Roku may have to pay fees to TV OEMs now that everyone understands how valuable the platform potentially is. Given OEMs have been completely commoditized, it may be difficult for an OEM to demand such a deal from Roku.

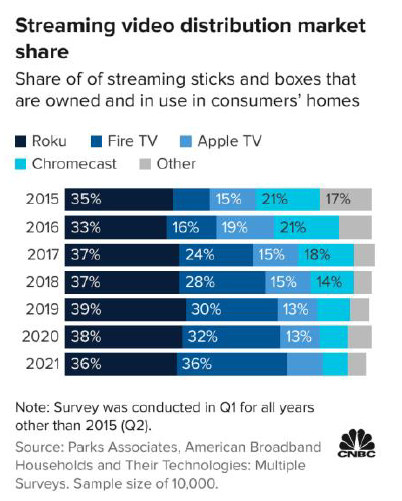

Bears point out how Amazon Fire sticks have matched Roku’s market shares in the US. But one Roku bull that I spoke with mentioned he is not too concerned about Amazon’s rise in the dongle/sticks market even though both Amazon and Roku have more than 50 mn active accounts. Ultimately, all of our TVs will become smart TVs and once a customer buys Roku branded TV, dongles are likely to become irrelevant. Bulls believe Roku branded TV is indeed Roku’s ticket to leverage in the media ecosystem. Since TV has 5-6 years of shelf life, dongles are just stop-gap solution to make all our “unsmart” TVs smart, but eventually we will all buy the smart TV. If Roku can maintain its dominance in the smart TV market, it will have the OS real estate in TV, which bulls believe will prove to be extremely valuable and hence will give them leverage in media ecosystem. As per one bullish analyst, the competitor he is much more concerned about is Google.

Before delving into Google vs Roku details, let me explain why Amazon is considered a weaker threat when it comes to the big screen TV business. Amazon Fire TV is a forked version of Android. However, Google’s recent policy prevents you from producing devices with a forked version of Android and the OEMs run the risk of losing access to Google apps, including the Play Store. Quoting from this piece:

“LG and Samsung both produce smartphones as well as TVs. When the companies agree to license Android for smartphones or TVs, they also agree not to use a forked version of Android no matter what product they are producing. Meaning, neither company can create a TV running Fire TV OS, or else it would lose access to the Play Store and Google apps on its smartphones as well.”

Why is Google a bigger threat for Roku? While Google doesn’t have much of a stronghold in the streaming stick market in the US, they can be a potent player globally in the TV market. They have recently re-branded Android TV to Google TV, which seems to be noticeably better than the earlier version. Google partnered with Sony and TCL for its smart TVs. I don’t know whether Google is paying them any fees to partner with Google, but if it does, that can potentially be uncomfortable development for Roku. As I will discuss shortly, Google is much bigger threat in international market. Google reported for the first time that it has 80 mn active devices worldwide in its TV platform, almost ~60% higher than both Amazon and Roku. Majority of these accounts are outside the US even though Google mentioned Google’s TV OS has seen “more than 80% growth in the US alone”.

If that were not tangible enough threat coming from Google, the recent spat between Roku and YouTube made it abundantly clear things are unlikely to be peaceful between these two platforms.

Just two months ago, Roku emailed its customers that "recent negotiations with Google to carry YouTube TV have broken down because Roku cannot accept Google's unfair terms,". For the uninitiated, YouTube TV (which is live TV), and YouTube the app (mostly user generated videos) are different. So what are these “unfair” terms by Google?

Roku alleges Google asked them to create dedicated search result row for YouTube within Roku OS and wanted YouTube search results to have more prominent placement. Google apparently demanded that Roku block search results from other streaming content providers while users are using the YouTube app. Roku also mentioned Google required Roku to use certain chip sets or memory cards that would force Roku to increase the price of its hardware product. Google denied all these allegations.

Roku bulls mentioned to me that Google is the loser here. Roku doesn’t make money from YouTube anyway, so there is no point in giving in to Google’s demands. YouTube TV has 3 million subscribers and if ~30-40% of them are watching on Roku, it is Google who is not being able to make money here (note: existing YouTube TV subscribers on Roku can still watch YouTube TV, but if you haven’t subscribed already, you won’t be able to access YouTube TV from Roku anymore). I think bulls are deeply underestimating the potential second-order effect.

I have a sneaky suspicion that YouTube TV is just a start of the much bigger battle between Roku and Google which will eventually peak at YouTube *the app*. If YouTube the app becomes unavailable at some point on Roku OS, I don’t think there are too many customers out there who would buy Roku branded TV. Even existing Roku customers would probably buy a Fire stick or Chromecast to ensure they can watch YouTube. Retailers and OEM would also certainly rethink their deals with Roku. YouTube, of course, knows how powerful they are. In fact, Roku mentioned a very peculiar term in their press release regarding this dispute when it said Google is attempting to use its “YouTube monopoly”. While I chuckled at first, I think I will be hard pressed to find a product in the age of internet that has created far more value for the world compared to what it captured for itself. As a result, a “YouTube monopoly” has been formed without which I don’t think any smart TV may have a hard time thriving.

Bulls cite the antitrust concerns and how much Google is already tied up to many lawsuits. That can certainly make Google re-think their approach here and being a management-led (instead of founder-led) company, Google may end up taking the safer route. However, I will be surprised if Google doesn’t make a concerted effort to win the smart TV OS market.

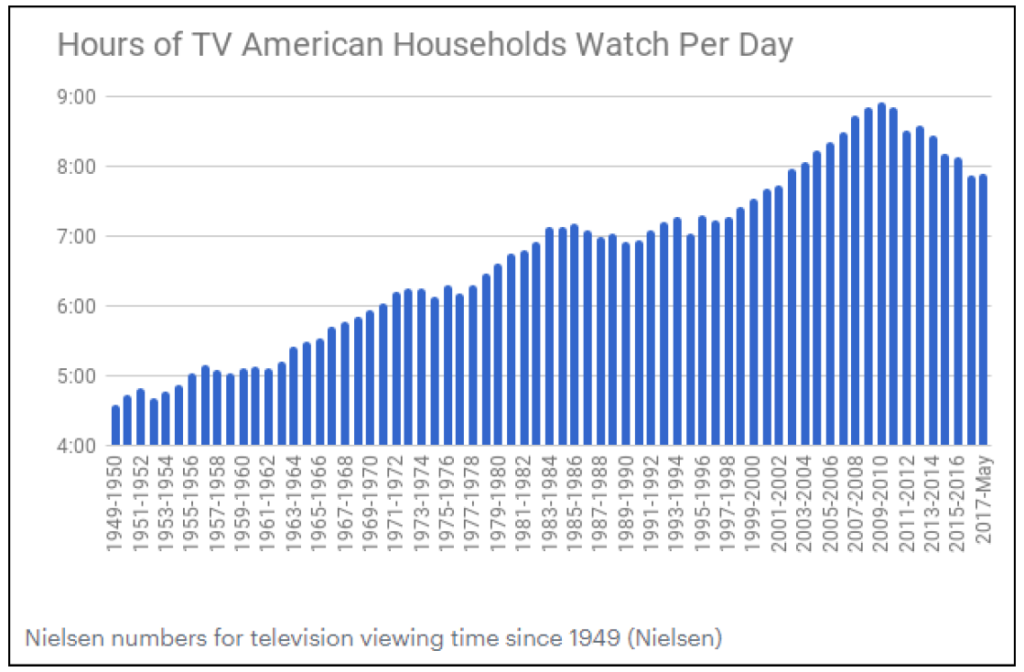

There are only a few companies out there who know about advertising and search as much as Google does. As TV is shifting from linear to connected world in which both search and advertising have a huge role to play, I am not surprised that Google is tempted to take hardline against Roku. In fact when you look at the number of hours an American household watch TV per day (~7-8 hours), that is most certainly a lot of ad dollars especially if you can get a lot first-party data to target ads much more effectively than the linear TV world could. Also with its strong position in mobile, I think Google is unlikely to concede TV to Roku/Amazon without giving a proper fight.

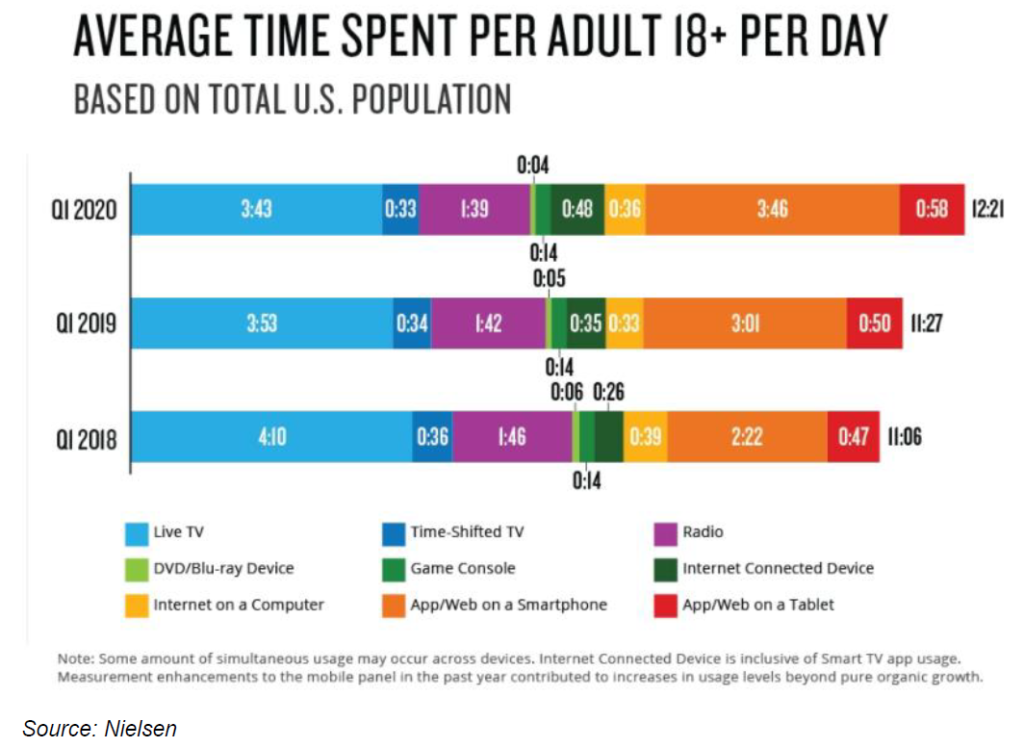

I do have a few concerns about TV watching hours and how sustainable it is in the long run. As you can see above, TV watching hours peaked in late 2000s, and gradually declined in the last decade. This time has mostly shifted to smartphone and apps as shown below. I think it’s fair to say all of our smartphones are going to be even more interesting in 5-10 years than it is today and hence smartphones/apps may continue to take time share from TV. Moreover, VR/AR or any other new visual platform may just completely bypass the TV platform and time share of TV can go down even further. SVODs are less susceptible to small changes in engagement since as long as Netflix can produce “Stranger Things” or HBO can produce “Game of Thrones” every few months, I am not going to unsubscribe. SVODs really get paid for superior content, not for streaming hours. However, for an AVOD, they need to convince us every day, in fact every minute, that we should spend our time watching their content. While I do think we will continue to watch Sports and AVOD content for years to come, I have a hard time believing that it will be 7-8 hours of household hours per day 5-10 years from now.

Moreover, a lot of TV watching hours are watched by older population (65+) as they watch more than 7 hours of TV per day. The old of tomorrow, I believe, will also be more fascinated with their phones possibly with more active and engaging content and may spend less time passively consuming TV. When I mentioned these concerns to a bull, he mentioned these are really long-term concerns and may not have any meaningful impact in the next 3-5 years. While I nod in agreement, you will see in section 4 that the valuation of Roku demands to have some comfort with these long-term questions as well.

International

In 2015, Roku first launched its Roku-branded TV in Canada. Today, they have 31% market share in Canada. Roku launched its streaming players in Mexico in 2015, although I’m not sure when they started selling Roku TVs in Mexico. Currently, they are #2 in terms of market share in Mexico, followed by Samsung. TCL just launched Roku TV in UK in 2021. Roku now has presence in France, Ireland, Brazil, and some other LATAM countries as well.

Roku’s strategy is simple: go to international markets by partnering with OEMs to produce cheap, quality smart TVs, grow active accounts to reach a certain scale, and then monetize user engagement on the platform. Bulls believe this playbook can work in multiple countries.

While Roku has been in Canada and in Mexico for considerable time, I am curious to see how they fare in Europe where they currently have high single digit percentage market share and currently behind Fire TV, Google TV, and Samsung. I think Fire TV and Google TV are both going to be fierce competitors in the international markets. As mentioned earlier, Google already has half the market share in Asia. Given Prime’s growing presence in Europe and other international markets, I believe Amazon too can cause a lot of concerns for Roku’s international ambitions, especially if either of them becomes willing to pay the OEMs to be the OS on the smart TV. If Google/Amazon cannot match Roku’s cost competitiveness, they can just match the difference (or more) and pay the OEMs for the privilege of being OS on their TVs.

Source: https://9to5google.com/2021/05/03/roku-global-streaming-marketshare-drops/

I am particularly curious to understand why Amazon’s Fire TV platform would not be much better at targeting ads than Roku. If you are a Prime member, Amazon obviously has much granular level data than Roku has. When users’ purchasing data on Amazon is triangulated with their content watching data, Amazon should be able to build a superior ad product than Roku. I asked this question to a Roku bull. He thinks advertisers still feel more comfortable with Roku because it’s a much more open platform than Amazon is. Google and Amazon are walled garden and their ad products are more black box than Roku’s is. You can buy ad inventory on Fire TV but you have limited visibility on many of the data points relative to what one could get on Roku. That is perhaps fair, but black box or not, if Amazon can come up with better ROAS on its platform, advertisers may not need to understand all the details. I don’t know how ROAS compares across the platforms, so I am just talking out aloud here, but if you do have any insight on this point, feel free to drop me an email/DM.

The other aspect I have been thinking about Roku’s international ambition is local content. If Roku needs to have strong presence in international markets, especially non-English spoken countries, it certainly needs to invest in local content for TRC. Such investment can be capital intensive if they want to acquire content, and big tech obviously have an inherent advantage when it comes to deploying capital. If Roku wants to focus on licensing, Amazon/Google can potentially bid up licensing costs as well.

Let’s now move onto valuation discussions and understand the opportunity and concerns with a quantitative lens.

Section 4: Valuation/model assumptions

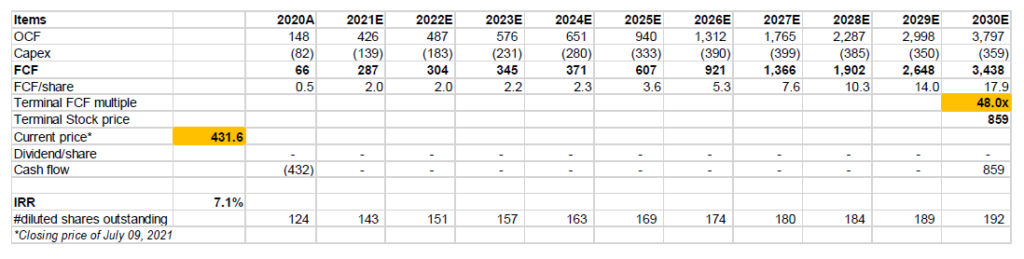

If you are reading my deep dive for the first time, I encourage you to read my piece on “approach to valuation”. I follow an “expectations investing” or reverse DCF approach as I try to figure out what I need to assume to generate a decent IRR from an investment (in this case ~7%). Then I glance through the model and ask myself how comfortable I am with these assumptions. As always, I encourage you to download the model and build your own narrative and forecast as you see fit to come to your own conclusion. None of us have the crystal ball to forecast 5-10 years down the line, but it’s always helpful to figure out what we need to assume to generate decent return.

Let me discuss the model first, and then I will elaborate on valuation.

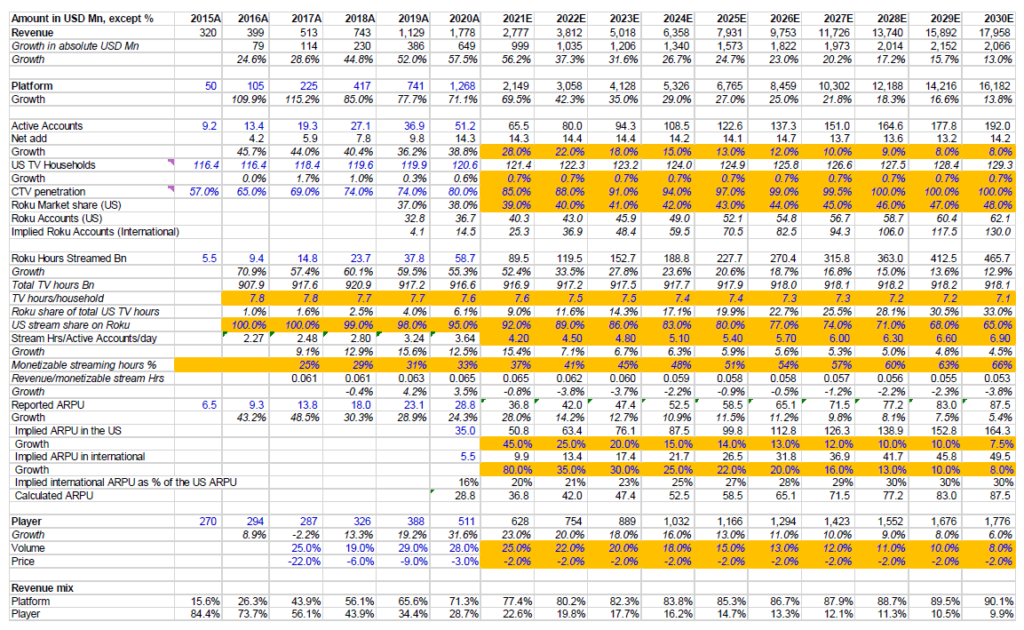

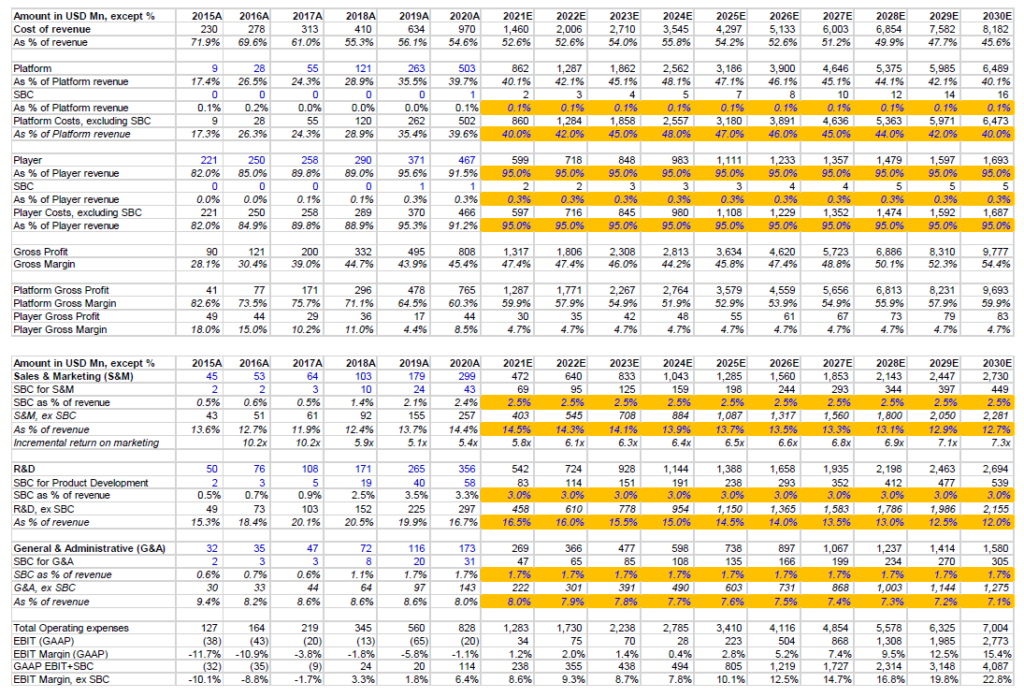

Revenue: As you can see below, Roku’s revenue in 2030 is “priced” to be ~10x of what it generated in 2020. I will mostly focus on Platform revenue which is ~70% of the revenue today and I expect to be ~90% of total revenue by the end of this decade.

The two primary drivers for platform revenue in my model are active accounts and ARPU. Number of active accounts is assumed to reach 192 mn in 2030. I have attempted to segment the active accounts into US and international although Roku does not disclose this. There are 120.6 mn TV households in the US, 80% of which has already been penetrated by CTV. Since Roku had 38% market share in the US in 2020, it implies Roku had 14.5 mn active accounts in international segment. I assumed CTV to have 99-100% TV market share by 2026 (highly likely in my opinion) and Roku to gain 10 percentage point market share in the next 10 years. As described in section 3, this can prove to be very difficult since Amazon Fire stick’s market share increased from 24% in 2017 to 32% in 2020 (some data shows 36% market share for AMZN in 2021) whereas Roku’s market share hovered around 37-39% during the same time. With Google’s renewed focus on smart TV, I struggle to see how Roku will gain further momentum in market share in the US. Perhaps much more importantly, even if we assume that Roku will be able to post the US active account numbers, the assumptions embedded in international markets active accounts is more revealing. As per the model, international is assumed to exceed US active accounts by 2023 and by 2030, international active accounts will be more than double the US active accounts. The pace of acceleration needed is quite incredible, especially since we have not seen such momentum in international markets from Roku before. When we consider the competition from Amazon and Google both of which can move faster than Roku and burn capital without much repercussion, I believe the bar for Roku in international markets to be quite high.

Once I have segmented active accounts into US and international, I have then assumed ARPU for these two segments in a way that matches the overall ARPU reported by Roku. Roku reported ARPU of $28.76 in 2020, so I assumed $35 ARPU for US accounts and $5.5 ARPU for international accounts. I then grew these ARPUs in a way so that US ARPU ends at $164 and the international ARPU ends at ~30% of the US ARPU in 2030. Why?

I have looked at Facebook’s ARPU in 2020 which was $164 in North America and EMEA ARPU was $51 or 31.1% of North America ARPU. It is very hard to predict ARPU with any precision and frankly, I am not sure whether this is conservative or aggressive. Bears may argue Facebook has the best ad platform in the planet and anchoring ARPU based on FB may prove to be too aggressive. On the other hand, bulls may argue Roku’s platform revenue does not only consist of ads, but also non-ad revenues as discussed before (I think by 2030, it will be ~90% ads for platform), and Roku’s ad targeting capabilities in the CTV world is a step function change compared to the linear world, so if anything, 10 years may prove to be too long a time for Roku to match Facebook’s ARPU. Although I struggle to pick a side on this point as I see some merit on both cases, it is a number I will closely follow to evaluate the stock going forward.

Given the difficulty of forecasting ARPU, I have also looked at other ways to figure out the implied assumptions in the forecasts. Since Roku reports total streaming hours on Roku platform, we can calculate stream hours/active account per day which was 3.64 hours in 2020. I have increased streaming hours/active account by 90% in the next 10 years to reach ~7 hours/day. Please note multiple persons can use one account, so it does not mean one person is assumed to watch 7 hours of TV every day.

I remain, however, somewhat incredulous that an American household will spend 7 hours per day to watch TV when they will have smartphone (which is likely to be even more interesting than it is today) and who knows what else. Of course, not all these streaming hours and engagement is quite monetizable if most of it happens on SVOD. As per the Nielsen data I shared in section 3, nearly two-third of streaming happens on SVOD. If we assume the same for Roku platform, we can calculate revenue per monetizable streaming hours on Roku. I assumed by 2030, the mix between AVOD and SVOD will flip, and two-third of the streaming content will be AVOD and hence monetizable by Roku. As you can see below, my platform revenue forecasts which is driven by ARPU implies a downward pressure on revenue/monetizable streaming hours. Given the ARPU mix shift from US to international, it is not surprising. The objective of this exercise is to have an explicit understanding what is being implied in the forecasts rather than aiming for a prediction. In aggregate, if you ask me, I am somewhat uncomfortable looking at these implied assumptions required to make the topline 10x in 10 years.

Cost structure: I have incorporated some scale benefits for S&M, R&D, and G&A expenses, but the real debate/question is related to Roku’s Gross Margin. For player segment, I just assumed 95% cost of revenue (excluding SBC) in each of the next 10 years. I won’t be surprised if gross margin is even thinner than modeled here, but given the declining contribution of player revenue, it is not consequential.

What is much more consequential is the gross margin for platform segment. There are two competing things at play for platform gross margin: a) As Roku scales further and its ad targeting/monetization capabilities increase further, its gross margin may increase further, and b) As Roku licenses/acquire content for TRC both for North American consumers and more local content for international consumers, gross margin is likely to pressured in the next few years. However, if Roku continues to scale its active accounts in both domestic and international markets, gross margin should start going up in the long-term. These things are notoriously difficult to forecast, so I mostly just want to explain my thought process here. You can, of course, alter these assumptions to fit what you think is more reasonable which can differ from how I have modeled here. You can download the model here.

Valuation: To generate ~7% IRR, I had to use 48x terminal FCF multiple. Please note that number of shares outstanding is assumed to increase by ~55% over the next 10 years. If you rolled your eyes when I used 36x FCF multiple for CRWD, I can only imagine what you must be thinking about using 48x FCF multiple, but I will repeat that the multiples are function of interest rates, growth rates, ROIC, and competitive dynamics in an industry. If Roku can generate ~$18-20 Bn revenue in 2030, it will perhaps imply Roku has “won” the smart TV race. For such a company, in a low interest rate world, I find it credible that investors would be willing to pay a pretty high multiple to own such a company. While entry (and exit) multiples are certainly important and will play a role what sort of return you generate from an investment, I think the more important questions about Roku’s shareholders today is whether they will be able to post $18-20 Bn topline 10 years from now.

Section 5: Management, incentives and Capital allocation

As hinted in the very beginning, Anthony Wood is a successful serial entrepreneur and Roku has been by far his biggest success. Wood taught himself programing when he was 13 and there is very little doubt that he is wicked smart. Whatever the future may hold, I find it extremely easy to have a deep sense of admiration for Wood.

With ~16% stake of Roku, Wood certainly has skin in the game. If you want to explore more about Wood, I suggest you read this excellent substack on Anthony Wood. Let me quote one paragraph that perhaps encapsulates Wood’s brilliance:

“Greg Garner, a principal hardware engineer at Roku and a longtime friend and colleague of Wood’s, calls him a triple threat. “Anthony’s very technical. He understands the hardware and the software, which is very rare,” Garner said. “And I can’t figure out how he does this, but he somehow predicts future trends and can form a business around an idea a year or two before the trend hits.” Wood’s third threat, according to Garner: “He’s a risk-taker who encourages the same behavior in his employees.”

If you need even more reasons to acknowledge the genius of Wood, just know he was both CEO and CFO of Roku during 2002-2010 period before they finally hired someone else for the CFO role.

It does, however, seem Roku will have to navigate some treacherous path in the next 3-5 years. Wood is currently 55 years old, and I wonder how long he will remain at the helm. There has been lot of speculation of Roku being acquired over the years. Ben Thompson wondered in 2014 whether Facebook should acquire Roku, and WSJ hinted at Comcast’s potential interest in Roku as late as June this year. In a September 2018 interview with Vox, Wood made it clear that he was not willing to sell Roku:

“I think we’re in the early days of streaming, I think Roku will power almost every TV in the world. That’s a hugely valuable company. If we sold the company now, we’d be leaving all of that upside, we’d be giving that upside to whoever buys the company.”

With the benefit of hindsight, we now know Wood was certainly right as Roku’s stock increased more than 6x since that interview. Last month, Wood was interviewed by CNBC and his tone was, in my opinion, a bit less emphatic than it was in 2018:

“CNBC: Do you expect to be running Roku as an independently traded company ten years from now?

Wood: I have no idea. I’m happy running Roku right now. I have no idea what I’m going to do 10 years from now.”

Perhaps I’m interpreting too much from an innocuous answer, but it feels like he is more open to the idea of selling than he was in 2018. As a long-term investor, a potential acquisition deal is never part of my investment thesis, but if Wood is indeed open to such a possibility, I wonder whether he thinks he won’t be leaving too much upside on the table if he sells today.

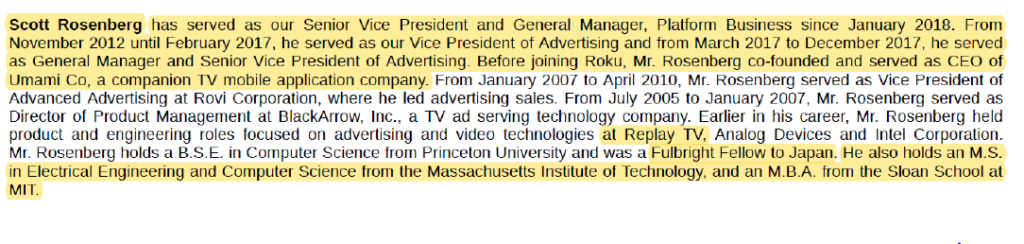

In case Roku remains an independent company in the long-term, it is perhaps highly likely Wood may not be at the helm in 2030 (perhaps not even 2025?). I have asked some investors/analysts who they think potential successors can be. Two names came up: Steve Louden (current CFO) and Scott Rosenberg (currently runs Platform Business). I consider Louden to be a very unlikely candidate. Roku is simply way too early in its journey to be led by a CFO and being a company that juxtaposes two very dynamic industries (tech and media), I would give Rosenberg a much better odd to succeed Wood. Louden has been CFO since 2015, but Rosenberg’s history with Roku/Wood goes way back to the “Replay TV” days. Roku is through-and-through an ad business and if Wood ever retires, I think shareholders will feel more comfortable if it’s led by someone who has been running the ad business for almost last 10 years. Rosenberg’s profile is mentioned below:

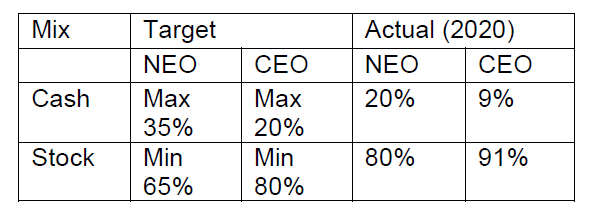

In terms of incentives, Named Executive Officers (NEO) and CEOs total compensation mix is shown below. There is no operating target metric as stock compensation is entirely dependent on the stock’s performance. In many ways, Roku has a quirky culture which many say resembles a lot with Netflix. I encourage you to read Roku’s culture memo (3 pages) which starts with this line: “Working at Roku is like being part of a professional sports team.” As an investor, purely from qualitative perspectives, there is certainly a lot to like about Roku.

Section 6: Final words

While discussing Roku with a bullish shareholder, he acknowledged the difficulty of finding a lot of answers today but encouraged me to think about owning companies such as Roku which can turn out to be big winner in the media ecosystem if they can navigate the landscape well in the next 3-5 years. I understand the batting average and slugging ratio math, but I think some of the “growth” stocks that I have recently written about are already priced as big winners. Investing today in company such as Roku imply I win some if I get it right, but lose a lot if things go wrong from here. If the bet were reversed i.e. I win a lot if I get it right, I would probably be more willing to buy such stocks today.

A lot of people mention Roku as trojan horse, but I think everyone in the media ecosystem today clearly understands what Roku is trying to become. It is hardly a secret anymore and the increasing disputes with Google, Fox, and a few others is a testament to that recognition. From here on, the path is highly likely to be more difficult for Roku. Having said that, good companies become great because they can navigate difficult periods with an aura of dexterity not shown by average companies. I am curious to follow Roku going forward.

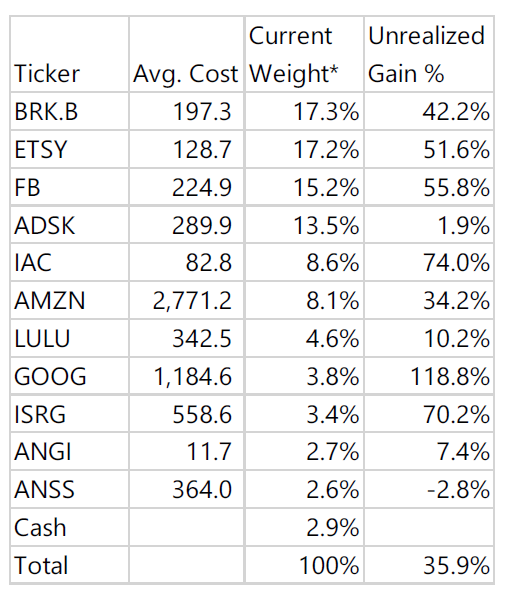

Portfolio discussion: Last month, I just bought Lululemon and made it ~4% position in the portfolio. Since my initial deep dive, I was following the company as I liked the business but not the valuation. I wrote an update last month and explained why initial skepticism on valuation is perhaps unwarranted today. If you missed that update, you can read it here.

I would also like to remind you that I am a shareholder of Google and Amazon, both of which are competing against Roku. As an existing shareholder of these companies, I may be biased while studying Roku.

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up as my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

*Based on prices as of July 09, 2021 (time-weighted YTD: +17.2%)

I encourage you to subscribe for the annual plan; annual subscribers receive the full schedule of deep dives in 2021. It will mean a lot if you encourage your colleagues/acquaintances to subscribe to my work. Your support is deeply appreciated. Thank you so much.

Recommended readings

1. Roku culture document

2. Elliot Turner’s presentation on Roku (bullish)

3. The Cynical Optimist’s piece: Why I Think John Malone is Wrong About Roku (bearish)

4. Secret Capital’s piece: Roku: The Gatekeeper to Modern Television (bullish)

5. Outliers’ piece on Anthony Wood

6. Fast Company’s piece on Roku’s early days inside Netflix

Disclaimer: All posts on “MBI Deep Dives” are for informational purposes only. This is NOT a recommendation to buy or sell securities discussed. Please do your own work before investing your money.