Big Tech's Deteriorating Earnings Quality

Disclosure: I own shares of Meta Platforms, and Amazon

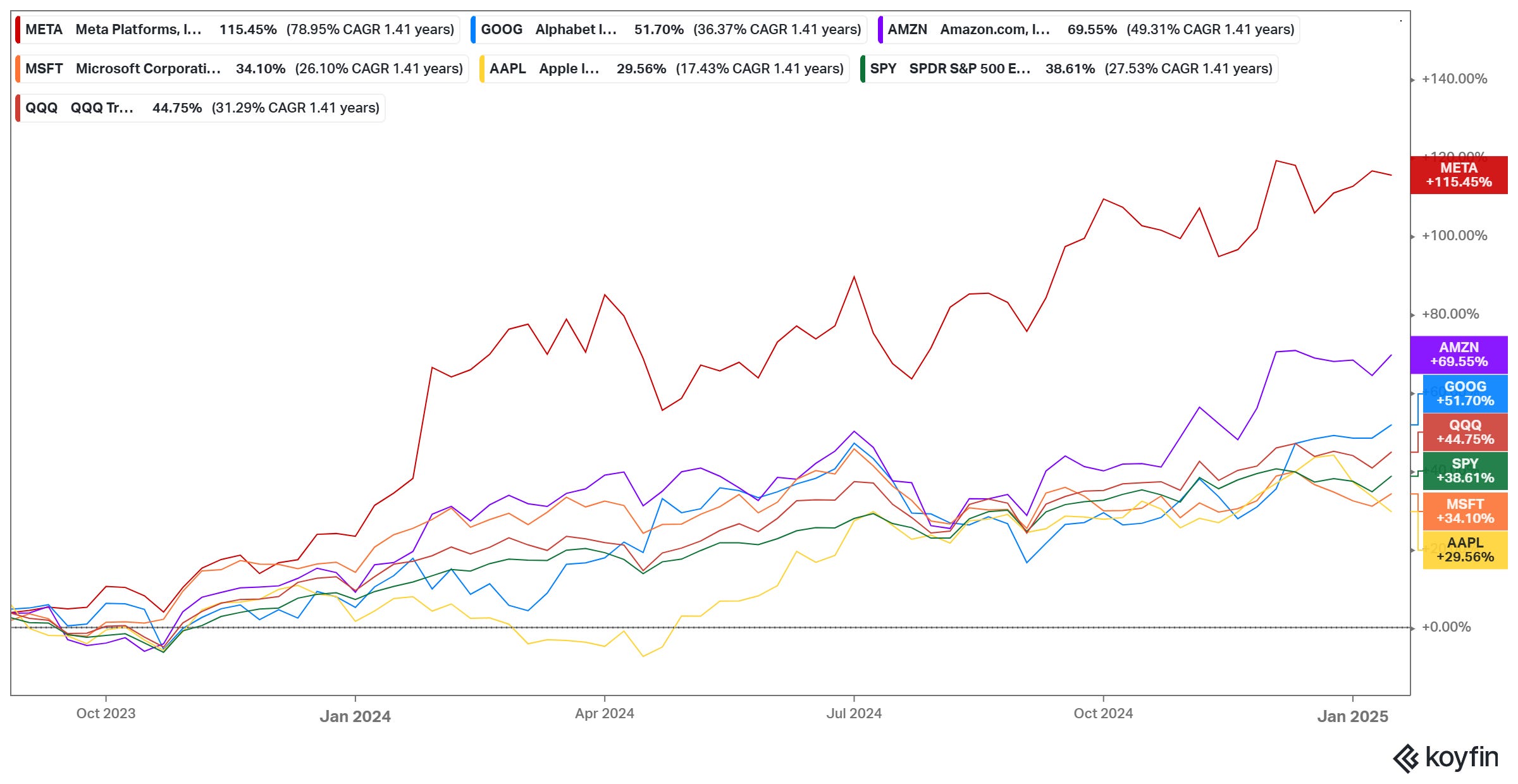

Almost one and half years ago, I wrote about “The Curious Case of Big Tech”, in which I highlighted that much of the big tech was actually “deep value” investments back in 2013. In fact, I also mentioned “Meta, and Amazon are currently trading at lower OCF multiple than they were trading back in 2013”. Both Meta and Amazon have comfortably outperformed both S&P 500 and Nasdaq 100 since then (not claiming any causal relationship, of course).

However, as the title of this piece suggests, I have a slightly different tune today. I am increasingly concerned about Big Tech’s deteriorating earnings quality. While some people started murmuring about this topic a few quarters ago, I would like to show through this write-up that big tech shareholders (including me) should perhaps indeed be at least slightly concerned. Moreover, as almost all the big tech are going to continue to invest in their capex hand over fist in the short to medium term, this concern may accentuate even further.

To make my case, I am going to focus on three companies within Big Tech: Microsoft, Meta Platforms, and Alphabet. Apple and Nvidia aren’t quite capex heavy, so this may not be a concern relevant for them. While it is very much relevant for Amazon, Amazon’s capex numbers are slightly convoluted given their retail AND cloud operations as well as the nature of my exercise (to be explained later).

Even though Amazon won’t be under my scanner in this exercise, it was Amazon which essentially sowed the seed of deteriorating earnings quality in big tech back in 2020. In 4Q’19 earnings call, Amazon announced to increase the useful life for their servers from three to four years:

…there's enough trend now to show that the useful life is exceeding four years. We have been – for our servers and we had been depreciating them over three years. So, we are going to start depreciating them on a four year basis." (Amazon 4Q'19 Call)

This led to similar adjustments at Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta a year later as they all decided to extend the useful life for their servers to four years.

Two years later, Amazon did it again. The useful lives for their servers were extended from four years to five years, and for their networking equipment from five years to six years. This time they tried to provide bit more justification why this isn’t just “accounting change” out of thin air, but rather a careful assessment of the reality:

As a practice, we monitor and review the useful lives of our depreciable assets on a regular basis to make sure that our financial statements reflect our best estimate of how long the assets are going to be used in operations…Although we're calling out an accounting change here, this really reflects a tremendous team effort by AWS to make our server and network equipment last longer. We've been operating at scale for over 15 years, and we continue to refine our software to run more efficiently on the hardware. This then lowers stress on the hardware and extends the useful life, both for the assets that we use to support AWS' external customers as well as those used to support our own internal Amazon businesses. (4Q’21 Call)

That sounds reasonable…except miraculously Alphabet, Microsoft, and Meta again came to the same conclusion just a year later. Basically, it’s the same meme I mentioned above.

Microsoft extended the depreciable useful life for server and network equipment assets in cloud infrastructure from 4 to 6 years. So did Alphabet. Meta, however, extended the useful life to five years. Given how quickly they all followed Amazon’s changes, it makes me wonder why they weren’t proactively carefully assessing the useful lives of their assets in the first place. Or if you’re cynical, you may think they may not have robust rationales anyway; they’re just doing it because a big tech peer gave them the “signal” that it can be done. Of course, higher useful life leads to lower depreciation expense which leads to higher operating profit. While shareholders all love ever increasing higher profits, it may be prudent to ask difficult questions to big tech management or ask them to provide a more detailed reporting on how they came to these re-assessments so quickly after years of “inefficiently” managing their servers and networking equipment.

Of course, not all big tech shareholders readily assume that something nefarious is going on here. Some understandably wonder whether the mix of PP&E itself may have contributed to lower depreciation rate in recent years. For example, land is not depreciated at all, and buildings are usually depreciated at 25-30 year period. So overall depreciation rate would go down if such mix shift occurs. However, we don’t quite see that in their financials.

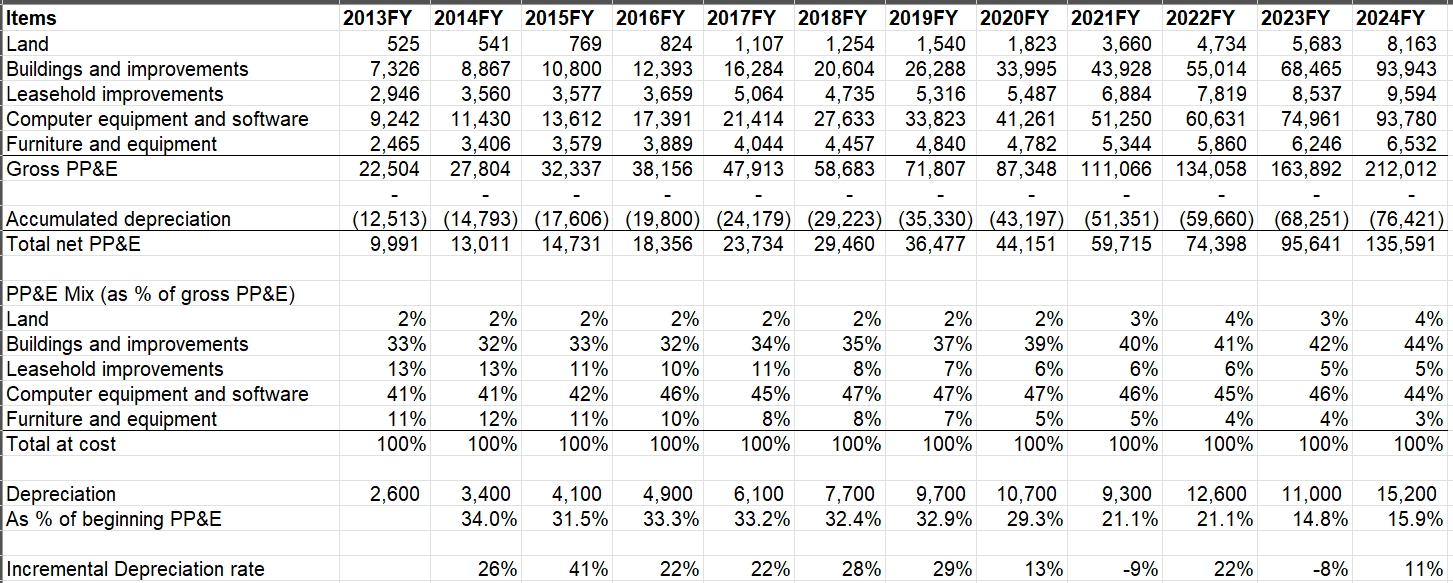

Let me show you Microsoft, Meta, and Alphabet’s more granular PP&E to substantiate this point. Let’s start with Microsoft.

Microsoft

Microsoft’s gross PP&E increased from $22 Billion in FY’2013 to $212 Billion in FY’2024. While the gross PP&E basically 10xed in the last 11 years, computer equipment and software was consistently ~40-45% of their gross PP&E. However, thanks to the changed depreciation schedule mentioned above, overall depreciation rate as a percentage of net PP&E declined from ~30-34% during FY’2014-2020 to just ~15% in FY’2024.

While one can perhaps legitimately claim that some of these computer equipment’s useful life may have been extended thanks to more innovative engineering and efficient management, that is perhaps equally (if not more) counterbalanced by increasing mix of GPUs in their PP&E. This is not controversial to say that the useful life of these GPUs are lot lower compared to when this cycle of extending useful life started anyway.

Here’s Rohit Krishnan in a recent piece: “The actual service life of H100 GPUs in datacenters is relatively short, ranging from 1-3 years when running at high utilization rates of 60-70%.”

Ben Thompson in his recent interview with Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross made the same point: “you have a data center, which is I think a 30-year depreciation, and then the GPUs are I think accounted for in a five-year depreciation, but actually are unusable after about 36 months. So, you already have a problem there in terms of your accounting for the GPUs”

Given this context, these companies perhaps should face difficult time in maintaining their historical depreciation rate, yet we are seeing the opposite.

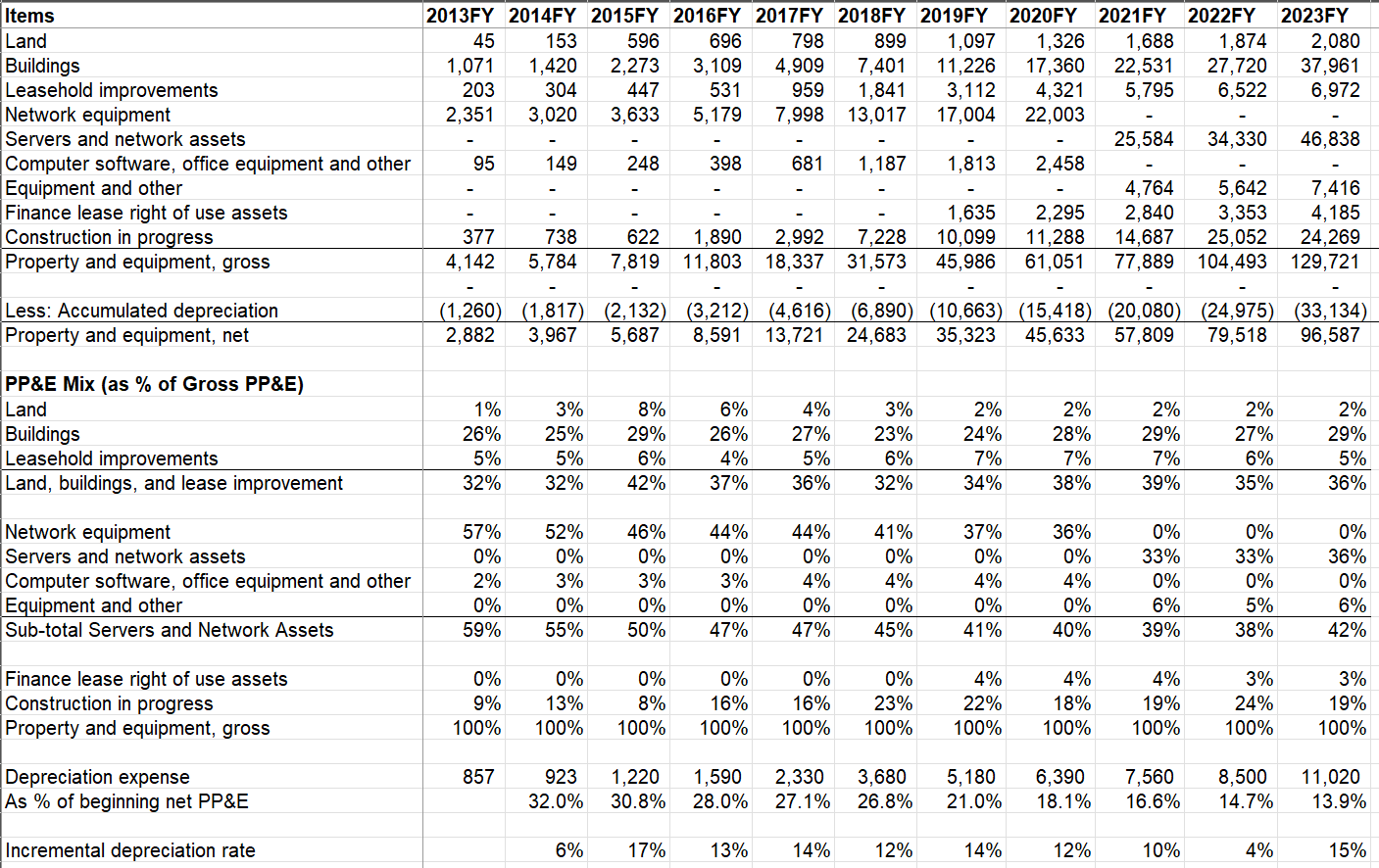

Let’s look at Meta now.

Meta

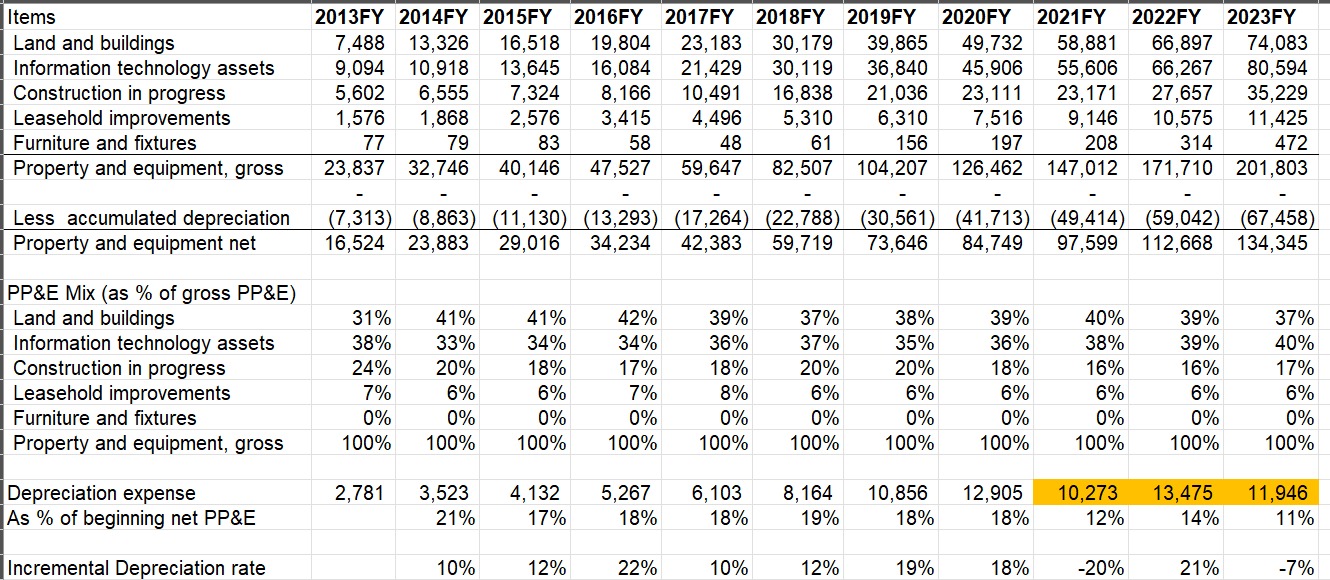

Meta made some changes in how they classify certain PP&E items in 2021. To make it more apple to apple, I have created a line item myself titled, “sub-total Servers and Network Assets”. In Meta’s case, we do see a somewhat noticeable mix shift within PP&E for servers and network assets as it declined from ~45-60% in 2013-2018 period to ~38-42% in the last five years. Like Microsoft, Meta’s depreciation rate as a percentage of beginning net PP&E declined from ~25-30% during 2013-2018 period to ~14-15% in the last two years. Unlike Microsoft, however, Meta’s incremental depreciation rate was somewhat consistent over the last decade.

In Meta’s case, there was indeed some mix shift in PP&E, but given Meta’s ever increasing GPUs (Zuckerberg mentioned they expect to have 1.3 million GPUs which clearly indicates these GPUs will be a significant part of their PP&E), the question remains just as valid whether we perhaps should expect to see depreciation rate to increase, instead of being down or steady going forward.

Now let’s look at perhaps the most interesting one: Alphabet.

Alphabet

Of these three companies, Alphabet is likely the worst “offender” in this exercise. “Information technology assets” has largely been steady in their PP&E mix over the last 10 years. When Alphabet’s net PP&E doubled from $42 Billion in 2017 to $85 Billion in 2020, their depreciation expense also doubled. So far, so good.

However, while their net PP&E increased by a whopping $50 Billion in 2023 compared to 2020, their annual depreciation expense has actually declined by $1 Billion during the same period. Those changes in useful lives certainly came in pretty handy for Alphabet.

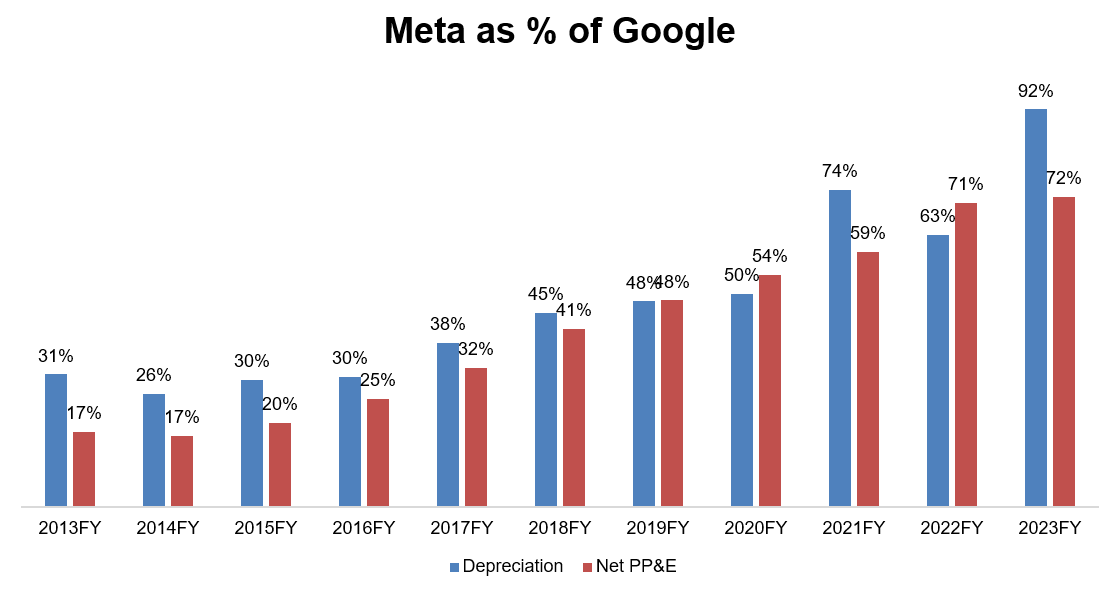

It almost doesn’t pass the smell test when I noticed Meta and Google reported almost the same depreciation expense in 2023 even though Meta’s net PP&E as % of Google’s was only ~70% in 2023. Given their network assets in the PP&E mix are kind of similar, I’m not sure why such discrepancy exists. Perhaps Google is much better than Meta in managing their assets!

While many may consider it “analysis paralysis” on accounting shenanigans, there may be important implications for these companies. Even though changes in depreciation schedule doesn’t have any impact on cash flow, since all these big tech companies are investing heavily in their capex, investors understandably pay more attention to their earnings these days than free cash flow in valuing these companies. If somewhat questionable depreciation schedule leads to higher reported profit and higher reported ROIC, investors can go a bit astray in assessing their fundamentals. This can become especially more important as the size of their PP&E grows which is almost certainly going to be the case in the short-to-medium term.

Thank you for reading. I will cover Google, Meta, and Amazon's earnings in the next couple of weeks.