Adobe: A Software Giant from the 80s

You can listen to this Deep Dive here

John Warnock and Charles “Chuck” Geschke, who met each other while working for Xerox, co-founded Adobe in 1982. John was leading a team at Xerox to build InterPress, a protocol for Xerox printers and became disillusioned as Xerox showed little interest in going to market with his product: “We sold InterPress throughout the Xerox organization for two years. They said, “Oh, we love it. We’ll make it a standard. We are going to put the locks on it and wait until all of our printers can do this before we release it.” Chuck and I found this totally unacceptable and realized, “That will never happen in our lifetime.” The only way to make standards is to get them out and just compete. I went into Chuck’s office one day and said, “Chuck, we can stay at a very cushy, wonderful job here. Or we could try to get something done.”

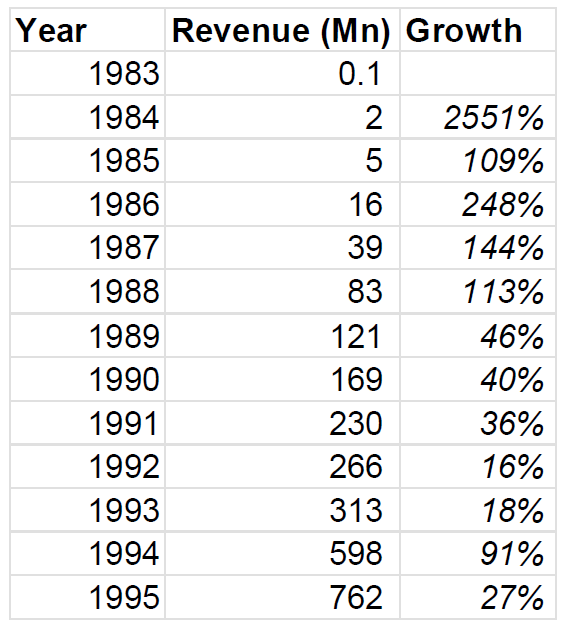

Chuck and John decided to leave their cushy jobs to start Adobe, which was named after a creek in Los Altos (near Chuck’s house). They developed PostScript, the device-independent programming language between PC and printer that could describe text, graphics, and images on one page. PostScript, along with the Apple Macintosh graphical user interface and laser printers, launched the desktop publishing industry in the 80s. Adobe found the product market fit right away and kept growing revenues at more than triple digit rates in the first six years since its founding. Apple (basically another Steve Jobs masterstroke) bought ~15% stake in Adobe in November 1984 for $2.5 Mn. Adobe went public in 1986, and when Apple decided to sell its stake in 1989 (alas, Jobs wasn’t there anymore), its stake was worth ~$84 Mn, a cool ~34x of its initial investment or ~102% CAGR over ~5 years. Apple, however, “missed out” on ~30% CAGR over almost four decades! I’m sure nobody is complaining at Apple, but why did Apple sell?

In 1989, although Adobe had 30 customers, Apple accounted for 29% of Adobe’s revenue and decided to work on a rival product of PostScript. Given the former partners were becoming potential rivals, Apple sold its Adobe stake. While Adobe’s sales decelerated dramatically in 1989, Adobe also laid out the groundwork to diversify its products. By the late 80s, Adobe launched two more products that went onto define their categories: Illustrator (vector-based editing software) and Photoshop (pixel-based editing software). While Illustrator was developed organically, Adobe licensed the Photoshop software in 1988 and eventually bought it outright for $34.5 mn in 1995. In 1991, Adobe launched Adobe Premiere (video editing software). The product velocity didn’t even stop there and in 1993, Adobe launched Portable Document Format (PDF).

The history of PDF is quite interesting. While PDF is by far the most pervasive digital document format today, John mentioned, “When Acrobat was announced, the world didn’t get it. They didn’t understand how important sending documents around electronically was going to be.” In fact, Adobe’s board wanted to kill the project, but John had a different vision in mind, “What industries badly need is a universal way to communicate documents across a wide variety of machine configurations, operating systems and communication networks. These documents should be viewable on any display and should be printable on any modern printers. If this problem can be solved, then the fundamental way people work will change.”

It wasn’t the private sector which internalized the value of PDF, but IRS which really made good use of PDF in digitizing its tax forms. In early 90s, IRS used to send mails to 110 million individuals during tax filing season. Given the complexity of tax code, these forms came with wide variety of exceptions for both businesses and individual taxpayers. By 1994, IRS started distributing tax forms in PDF format which accelerated the adoption curve.

Two things stood out to me while studying the first decade of Adobe: a) the product velocity of that early decade is nothing short of extraordinary. Photoshop, Illustrator, PDF…these are still household names even three decades later. There aren’t perhaps too many three-decade old software brands still dominating the market. Considering the natural obsolescence risk tech industry generally grapples with, it is a remarkable feat. It is likely that these software brands (I know I’m using the word “brand” loosely but still opting for it because while the code behind the software didn’t remain the same over the decades, brands such as Photoshop became verb) today generate vast majority of Adobe’s Free Cash Flow (FCF) today; and b) the persistence and resilience of the founders even at the face of lack of immediate traction of new software or losing a customer that contributes 30% of revenue really drilled down the paramount importance of founders in fast paced industry such as tech, especially in the early years.

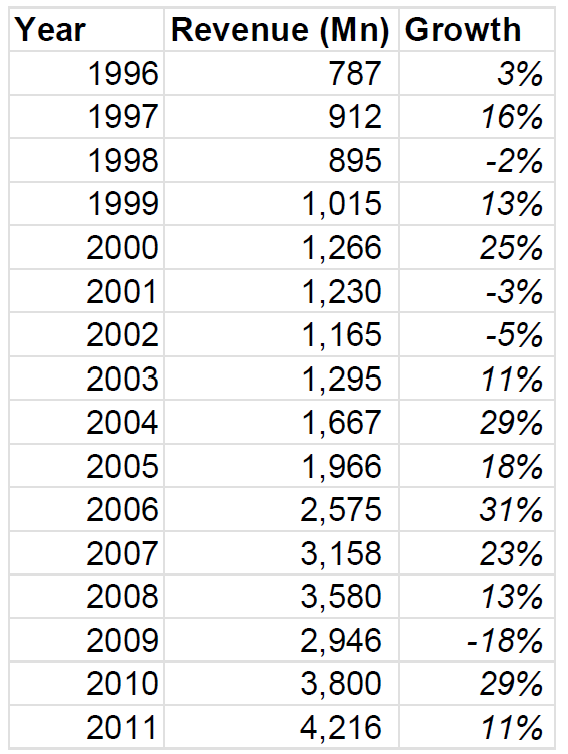

Speaking about the importance of founders, unfortunately they can also hold back their businesses at times. After growing like weed for more than a decade after founding, Adobe hit a rough patch from mid 90s to early 2000s despite the rise of web and tech bubble that ensued at that time. Knowledge at Wharton mentioned the following, “Yet that vision of what is technically and aesthetically “right” has also blinded the company to some of the major shifts in technology. During the rise of the web, Adobe sat on the sidelines longer than most companies partly because, as Warnock characterizes it, “early versions of HTML — from a design point of view — were awful.” From 1996 to 2002, Adobe grew its revenue at less than 7% CAGR. Warnock retired from CEO in 2000 and then from CTO in 2001. He, along with Chuck, co-chaired the board till 2017. After Warnock, Bruce Chizen became CEO who came to Adobe thanks to the acquisition of Aldus in 1994. During his tenure, Chizen himself made a significant acquisition: Macromedia for ~$3.5 Bn in 2005 and he later mentioned that Adobe was primarily acquiring Macromedia to get Flash. Then in 2007, Shantanu Narayen became CEO who is still leading the company today.

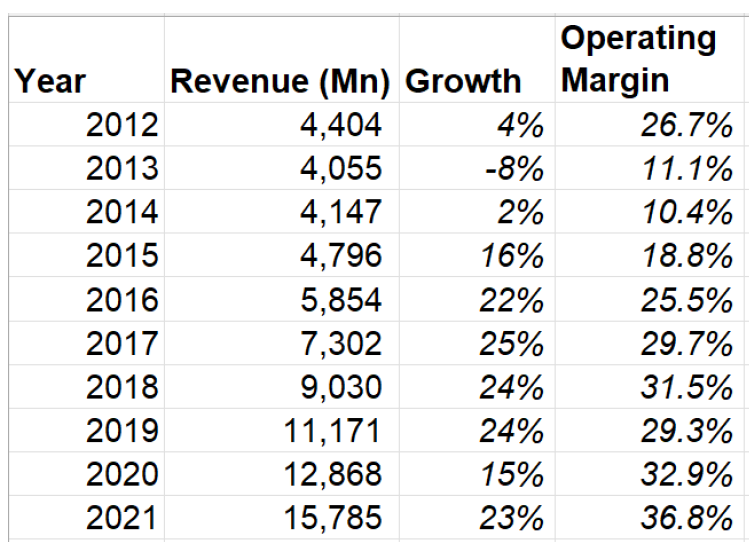

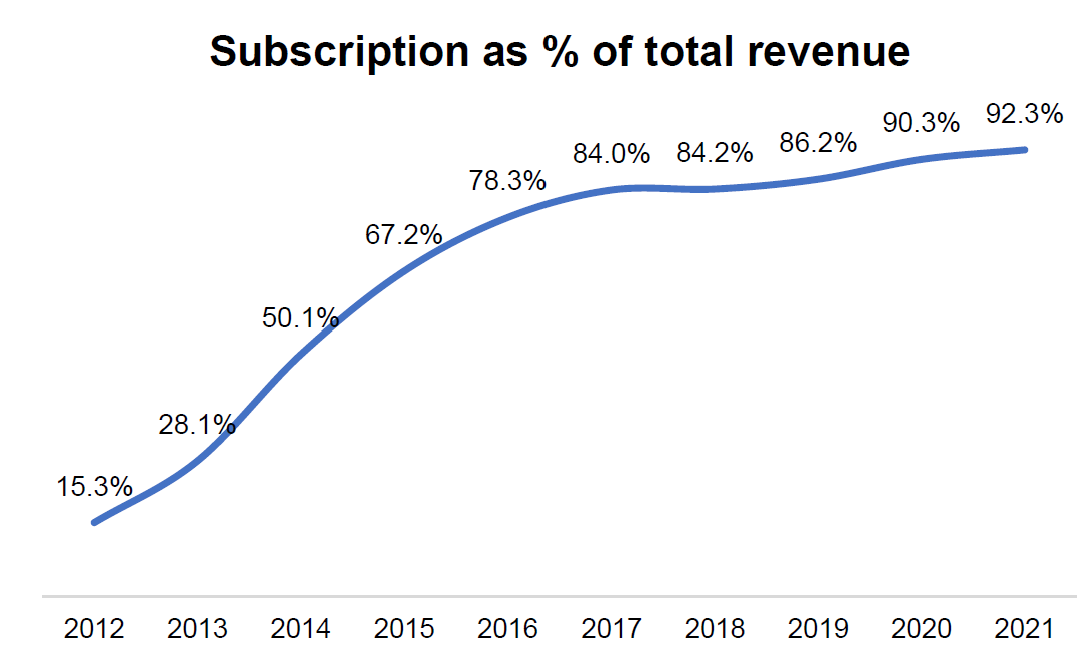

While Adobe somewhat got out of the slump it found itself during the rise of internet, sales continued to be lumpy and much more volatile in sympathy with the broader macro environment. During the global financial crisis, sales fell precipitously by 18% in 2009 and even during post-tech bubble recession, Adobe’s sales went down two consecutive years. Adobe experienced more pronounced volatility than most software businesses at that time because Adobe had only 19% recurring revenue in 2011, and the rest of the revenue was mostly generated by selling perpetual licenses (customers pay once and can use the software indefinitely). Narayen wanted to dampen this revenue volatility and wished to make the business more predictable and stable even in difficult macro periods. As a result, Adobe announced to switch to subscription model in 2011 and while for a couple of years, they supported both perpetual licenses and subscription model, they fully deployed resources to subscription business by May 2013.

By any measure, the decision to move to subscription model has been a resounding success. But it was far from an obvious decision at that time. Apart from dampening the volatility of the business, there were other important reasons behind Adobe’s change to subscription model. Under the perpetual licensing model, the number of units shipped was about three million for a long time, and the only way they could increase sales is by raising prices or moving customers to upgrade products. That’s exactly what Adobe was doing; for example, the perpetual license for Illustrator used to cost $399 in 2004, $499 in 2005, and $599 in 2008. Even though Adobe clearly had pricing power, the management perhaps suspected such a strategy has an expiry date, especially in the zero marginal cost of software world. Moreover, Adobe suspected there was a much bigger market out there which it was not serving as these customers weren’t ready to pay the upfront cost of the perpetual model. In an interview with McKinsey, Adobe management shared how they managed this stressful period:

“In November 2011, we announced our intentions to Wall Street—it was a full day of briefings, with financial analysts focused on communicating the strategy, ramifications, and financial expectations. One aspect of the strategy was that we were being more aggressive in shifting our Creative Suite (CS) business to the Creative Cloud. Another aspect was that we were doubling down on our cloud-based digital-marketing business. We decided to shift $200 million in operating expenses toward these high-growth opportunities. After we announced our plans, the stock price dropped by 6 percent, which actually was less than we had anticipated. It fully recovered within three months. We launched Creative Cloud and Creative Suite 6 (CS6), under the traditional perpetual-licensing model, in May 2012. So there was a period in which we were doing things in parallel. But after about a year, we felt ready to step on the accelerator and move everything to the cloud. In May 2013, we said we would no longer add new capabilities to the CS line, although we would continue to sell and support CS6.

We gave them “markers”—for instance, we said we were going to reach 4 million subscribers in 2015 and build up ARR. As the switch-over progressed, toward the end of 2013, investors became intrigued and started asking about longer-term objectives. So we projected the compound annual growth rate and earnings per share out three years and shared those metrics.

This was new for us; previously we had only given guidance one year out. The point is, we were transparent. We over-communicated. When we did that, and when Wall Street saw the traction we were getting with the initial release, the stock started to move.”

After being stuck at three million units under the perpetual licensing model, Adobe blew past its guidance of 4 million subscribers for 2015. Adobe exited 2015 fiscal year with more than 6 million subscribers. In my estimates, Adobe had more than 24 million subscribers to its Digital Media business (which is mostly Creative Cloud) in 2021, implying they indeed served just a fraction of the market under their old business model. Moreover, even though operating margin took an immediate hit following the switch to subscription as it went down from ~27% in 2012 to ~10% in 2014, it quickly recovered to ~26% in 2016, and in 2021, the operating margin (remember, this is GAAP, so I’m not ignoring SBC here) reached an envious 37%.

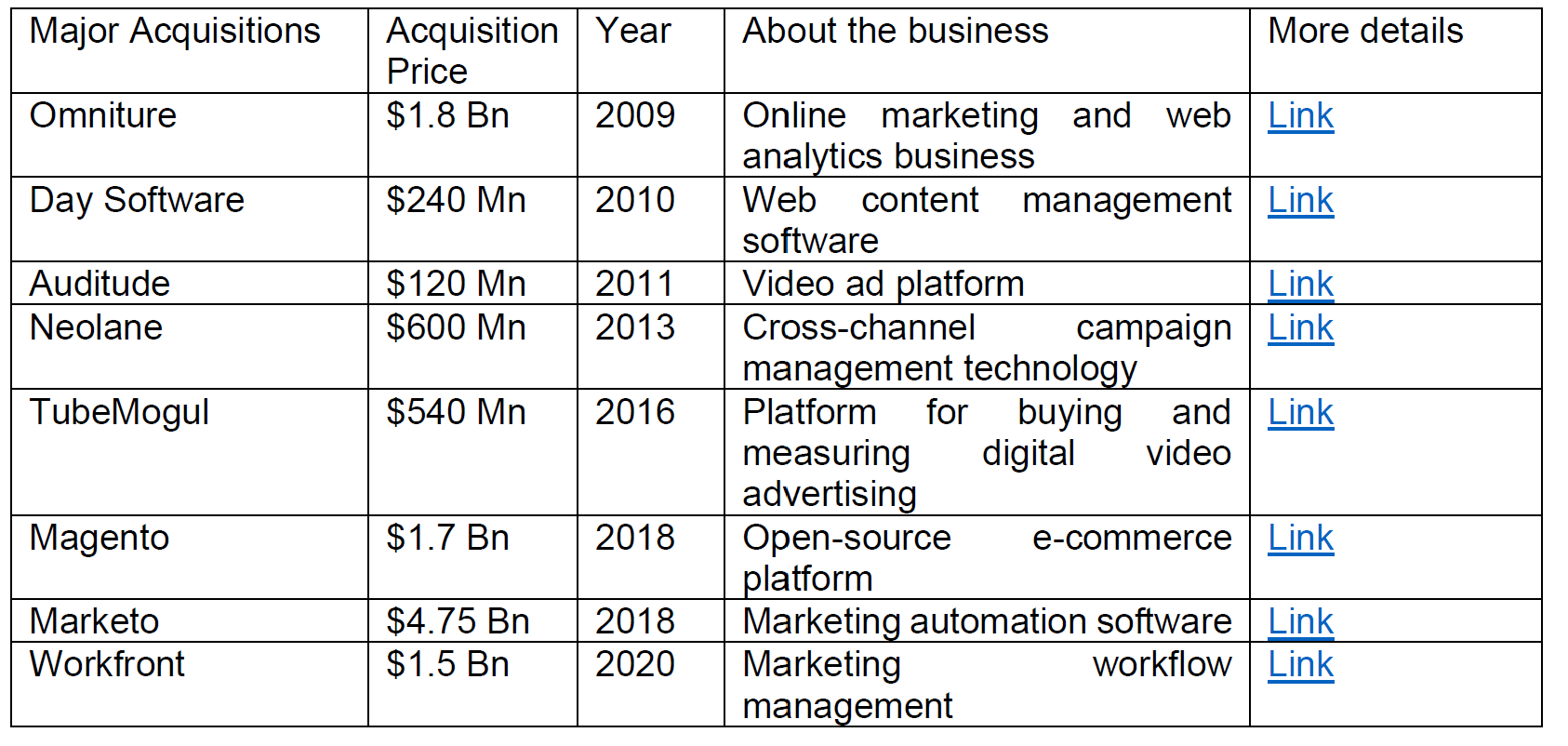

What made this transition perhaps even more impressive is not only Adobe continued its dominance in creative cloud but also expanded its business to a new segment over the last decade: Experience Cloud which Adobe got into via its acquisition of Omniture in 2009 for $1.8 Bn. Then in 2012, Adobe launched Adobe Marketing Cloud which was later renamed to be “Adobe Experience Cloud”.

Now that we have a good grasp on the history of Adobe, let’s get into the present in more detail.

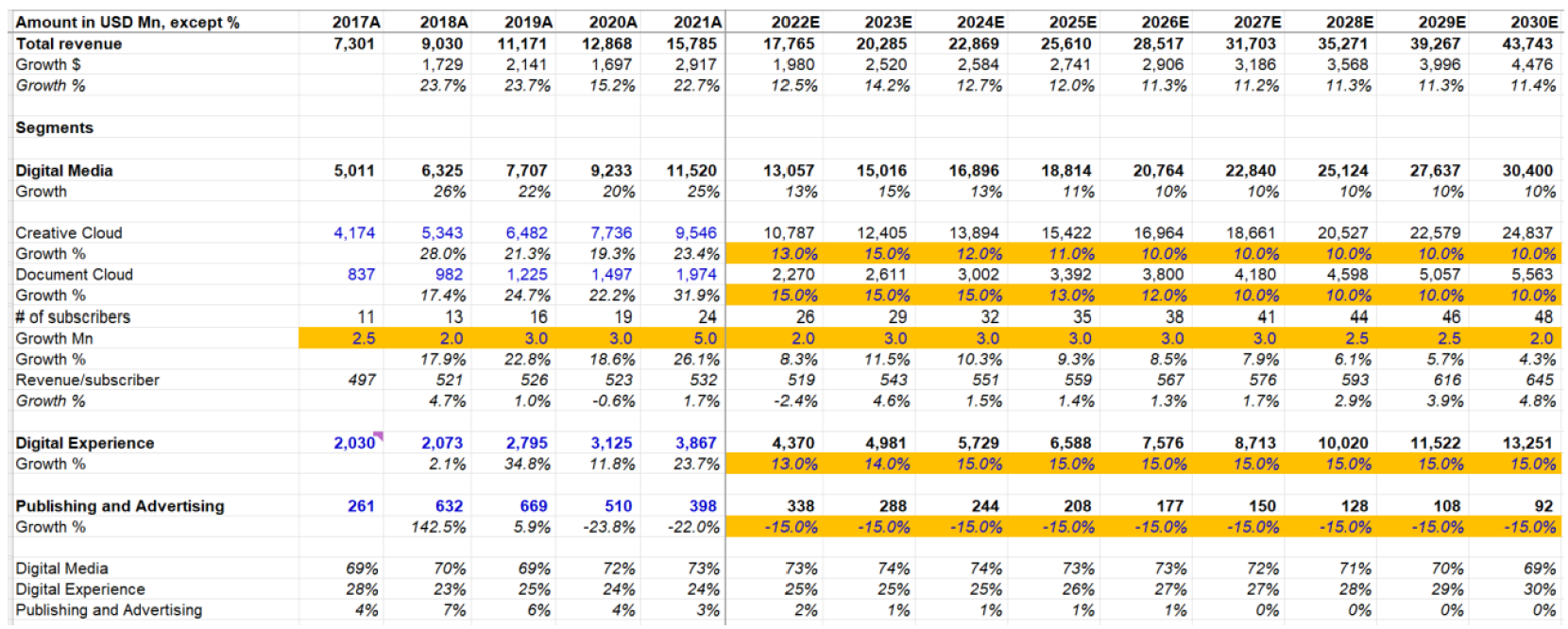

Section 1 Adobe’s Economics: I discussed Digital Media (including Creative Cloud, and Document Cloud), and Digital Experience segments and their economics and cost structure by segment.

Section 2 Total Addressable Market: Adobe’s Total Addressable Market (TAM) by segment as well as its penetration in these segments was highlighted in this section.

Section 3 Competitive Dynamics: Adobe’s competitive dynamics varies greatly depending on the segment. While Adobe absolutely dominates Digital Media segment today, Digital Experience’s dynamic is somewhat different. The durability of Digital Media’s “monopoly” is the focus on this section, but I also briefly touched on Document Cloud and Digital Experience as well.

Section 4 Capital Allocation and Incentives: Adobe’s capital allocation history under Shantanu Narayen (Adobe’s CEO since 2007) and management incentives are discussed in this section.

Section 5 Valuation and Model Assumptions: Model/implied expectations are discussed here.

Section 6 Final Words: Concluding remarks on Adobe, and disclosure of my overall portfolio.

Section 1 Adobe’s Economics

The vast majority of Adobe’s current revenue comes from subscriptions. While subscription as % of total revenue was only 15% in 2012, it was 84% of total revenue in 2017 and it gradually kept increasing in the revenue mix to reach 92% in 2021.

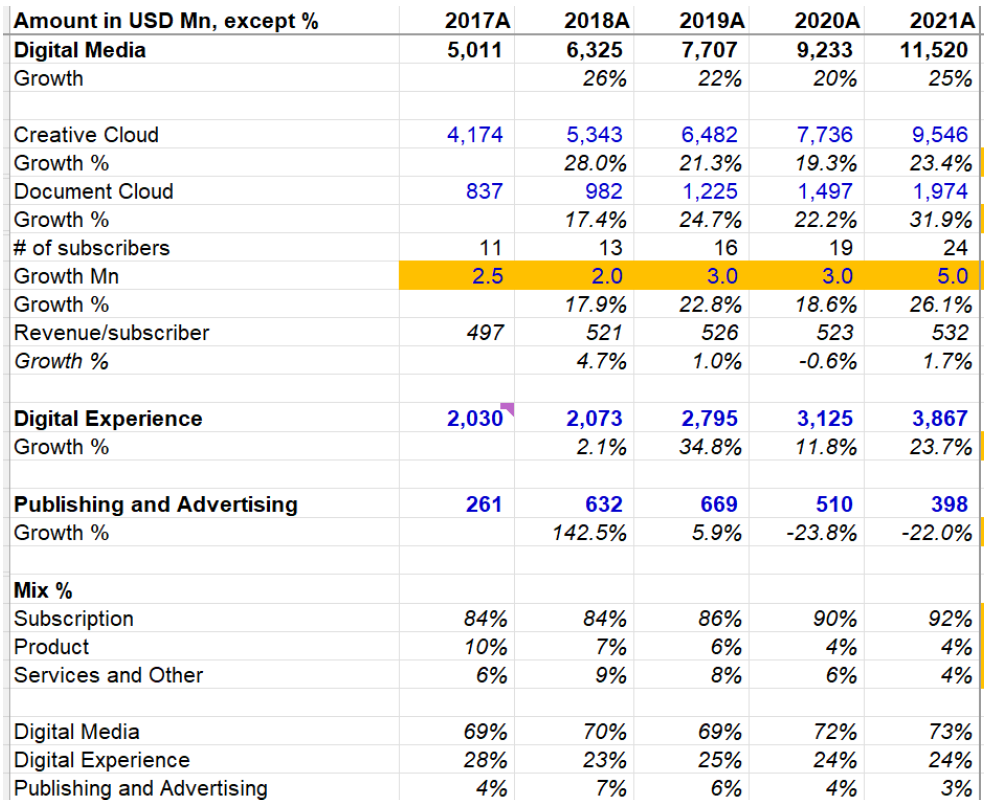

Adobe breaks down its revenue in broadly three segments: Digital Media, Digital Experience, and Publishing & Advertising which contributed 73%, 24%, and 3% to overall revenue respectively in 2021. Let me briefly discuss these segments separately.

Digital Media

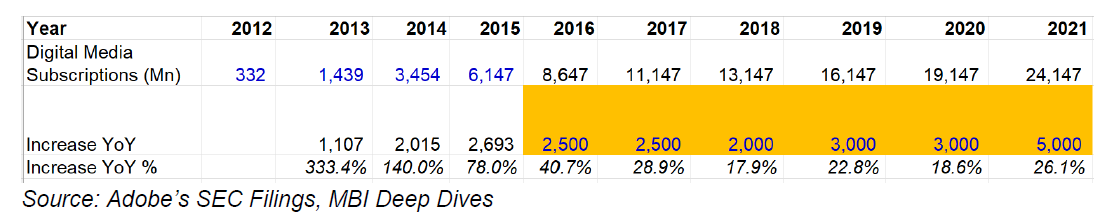

Adobe reports Digital Media in two categories: Creative Cloud (CC), and Document Cloud (DC). Adobe used to disclose subscriber numbers for Digital Media segment until 2015. However, since Adobe kept its prices fixed after moving to subscription model until 2018, we can make some educated assumptions (which I’ll discuss later) to estimate that Digital Media’s subscribers increased by almost four-fold in the last 6 years i.e. ~6 mn in 2015 to ~24 mn in 2021.

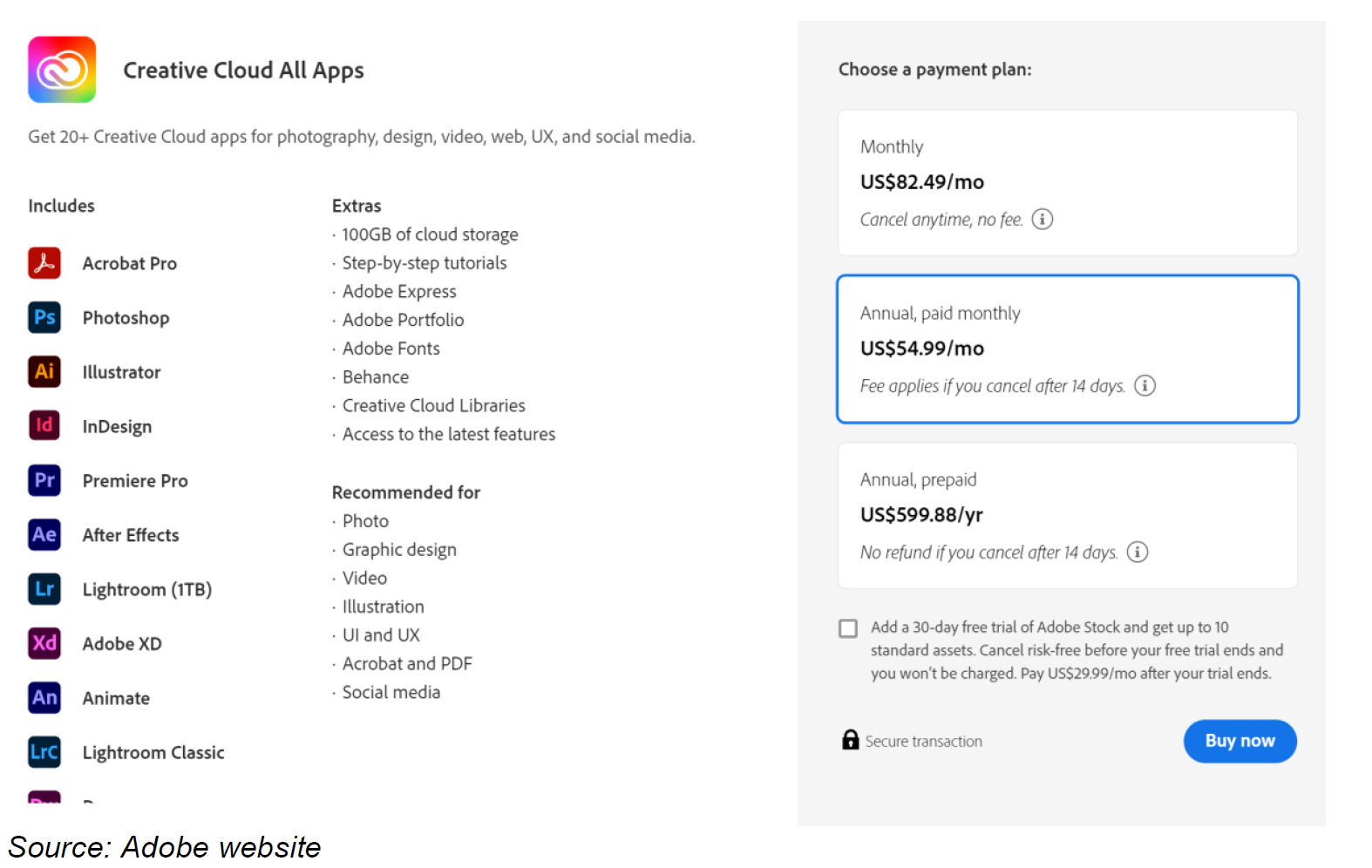

Creative Cloud: Creative cloud is cloud-based subscription solution for creative professionals and enthusiasts related to photography, design, video etc. While you can buy each of these apps a la carte, the whole creative cloud apps cost $54.99/month (which was recently increased from $52.99/month in March this year) for individual subscription. Please note that businesses, students & teachers, and schools & universities have separate pricing plans which you can explore on Adobe’s website. Since individual apps such as Photoshop and Illustrator cost $20.99/month each, any creative professional/enthusiast who needs at least three apps is better off just buying the whole creative cloud apps.

For context, the whole creative suite used to cost $2,599/year under the traditional perpetual licensing model back in 2012 compared to ~$600 per year under the subscription model. A typical customer under the licensing model used to buy a new license approximately every four years to access all the new features/updates, Adobe needs to keep a subscriber ~4.3 years to make the two models breakeven. The truth is most creative professionals who stop using Adobe are perhaps the ones who end up leaving the profession altogether. Therefore, the retention ratio, especially for enterprise customers, is likely to be extremely high. Moreover, as discussed earlier, because of the low upfront costs, Adobe’s products were able to reach a much wider creative enthusiasts who would probably not be willing to pay a few hundreds or thousands of dollars to edit a photo or video for non or semi-professional reasons. With the rise of social media and digital content, Adobe’s products reached an audience much bigger than it perhaps could imagine in 2010. If you want to have a quick understanding of these products, I suggest this 9-minute video which quickly summarizes 60+ Adobe products and what it is used for. Even though there are 60+ products, my guess is Photoshop (digital imaging and design app with editing and effects tools), Illustrator (vector graphics app to create digital graphics and illustrations for all kinds of media), Premiere Pro (video editing app) generate majority of revenue/usage in Creative Cloud.

Creative Cloud contributes 83% of total Digital Media and 61% of Adobe’s total revenue. As I will discuss later, it likely has even more outsized contribution to Adobe’s overall operating profit.

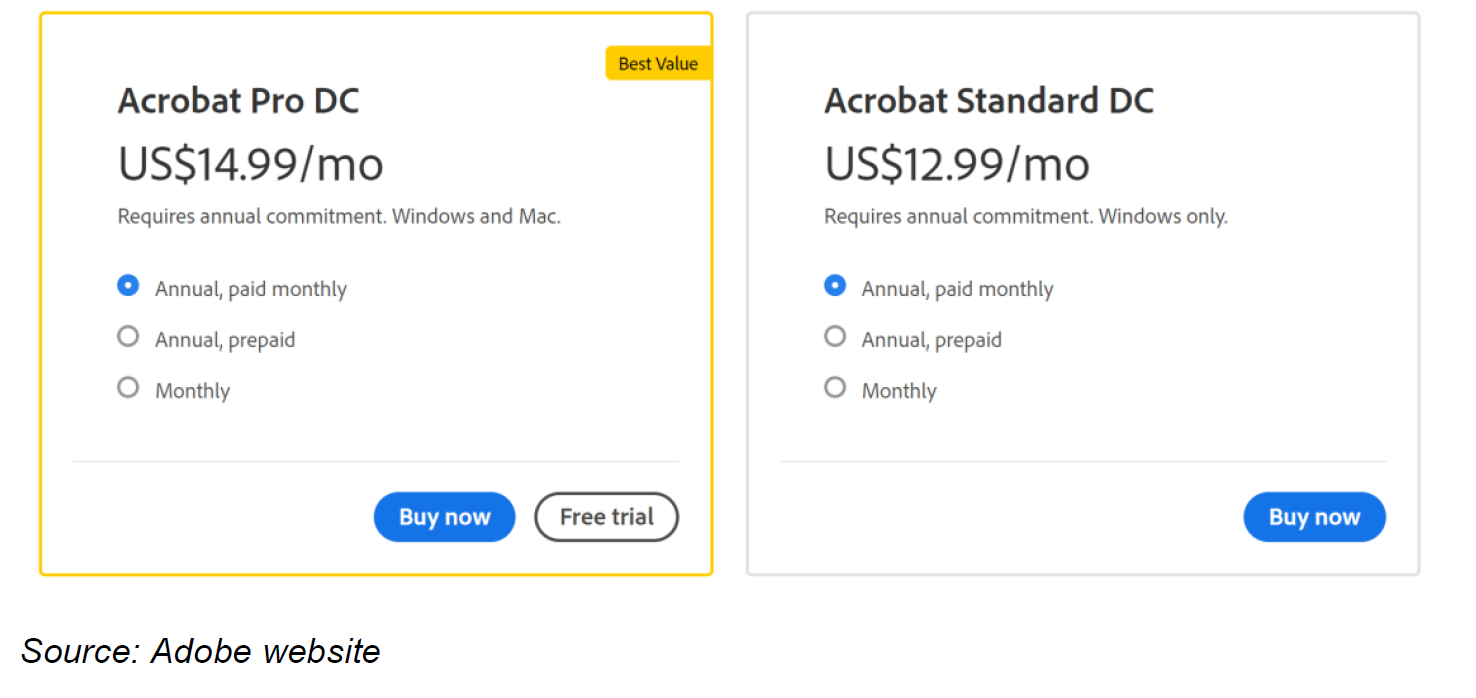

Document Cloud: Document Cloud business consists of Acrobat branded products which allow you to create, edit, export, combine, share, and collaborate on PDF documents. If you buy the whole Creative Cloud subscription, it already includes Acrobat Pro subscription, but you can also buy just Acrobat subscription for $14.99/month (individual pricing; different pricing available for businesses and students). Adobe Sign, which allows users to send and sign any document from any device, and Adobe Scan are also included in the Document Cloud segment. Unlike Creative Cloud, you cannot choose a la carte in Document Cloud, and everything is bundled together in Acrobat Pro/Standard subscription.

Document Cloud generated ~$2 Bn revenue in 2021 which contributed ~17% of total Digital Media and ~13% of Adobe’s total revenue.

Digital Experience/Experience Cloud: With its Omniture acquisition back in 2009 for $1.8 Bn, Adobe first showed real intent in building Digital Experience business, which was formerly known as “Digital Marketing” segment. Adobe explained the thinking behind building this business:

“Inside the company, we had this fundamental belief that there were broader market opportunities for us. Where content was being created and managed, when it was being consumed, and where it was going to be monetized—all of that was changing. We also believed that data were going to become more important. We already had a strong presence in content creation, and we saw an opportunity to broaden our presence in these areas.”

Adobe’s CEO Shantanu Narayen also expressed similar rationale later in an interview with Barron’s:

“We said (at the time of the first Experience Cloud acquisition), instead of just focusing on enabling people at the front end of [the] creation process, why don’t we really look at what role we can play in the management, monetization, and mobilization of all of this content.”

Digital Experience focuses on four key categories: content and commerce; data insights and audiences; customer journeys and marketing workflow which are all delivered on a common platform called Adobe Experience Platform.

Since 2009, I estimate Adobe spent at least $11.3 Bn in various acquisitions to build its offerings on Digital Experience; the actual amount spent on acquisitions related to Digital Experience is likely to be slightly higher since many of the purchase prices were undisclosed. Since 2009, Adobe spent $13.5 Bn in acquisitions which was ~38% of FCF Adobe generated during this period; therefore, Adobe spent almost the entire last decade spending ~$12 Bn (the only major acquisition related to Creative Cloud in the last decade was Frame.io for $1.3 Bn in 2021) to build Digital Experience business. For context, Digital Experience generated $3.9 Bn revenue in 2021 which contributed to almost quarter of Adobe’s overall revenue. However, as I will show later, Digital Experience segment is likely run close to breakeven or at loss from operating margin perspective.

One way to think about Adobe’s business is Adobe has an effective monopoly in Digital Media segment, especially Creative Cloud business and it deploys its monopoly derived cash flow to build another business in Digital Experience segment which tends to be oligopolistic in order to gain exposure to broader profit pool of the content/creativity value chain.

Let’s take a closer look at the economics of Digital Media and Digital experience to understand Adobe’s strategy. First of all, Adobe does not disclose segment wise operating margin, so I tried to estimate it myself. Before we delve into the margin related discussion, let me talk about the revenue breakdown. As mentioned earlier, Adobe does not disclose subscriber numbers anymore. I estimated they added 2.5 mn subscribers to Digital Media in 2017 (similar to their actual disclosed numbers in 2015), but then assumed net adds decelerated to 2 mn subscribers in 2018 as Adobe increased its Creative Cloud subscription price for the first time in that year since 2012. Then in 2019, the net add cadence was assumed to improve and finally in 2021, Adobe was materially benefited by Covid as digital content creation likely received significant boost in 2020-21. Given there was no pricing change, Creative Cloud’s growth in 2020-21 was driven by volume/subscriber numbers. Again, I don’t know the accuracy of the estimates; I’m just explaining my thought process behind the estimates, and you are free to change these estimates as you see fit. Based on these estimates, the average Creative Cloud subscriber spends ~$530/year. Although an individual subscription costs $600/year, I’m guessing the overall lower ARPU indicates some a la carte subscription for particular apps such as Photoshop.

One interesting fact is even though Digital Media business is ~3x the size of Digital Experience segment and grew almost entirely organically as opposed to acquisition driven growth in Digital Experience, Digital Media segment grew at 23% CAGR vs 17.5% CAGR for Digital Experience in 2017-2021. Adobe management perhaps wants to diversify their business, but the core business is doing so well that they’re not being able to diversify much despite spending a lot of money on acquiring companies related to Digital Experience segment.

Now let’s talk about margins.

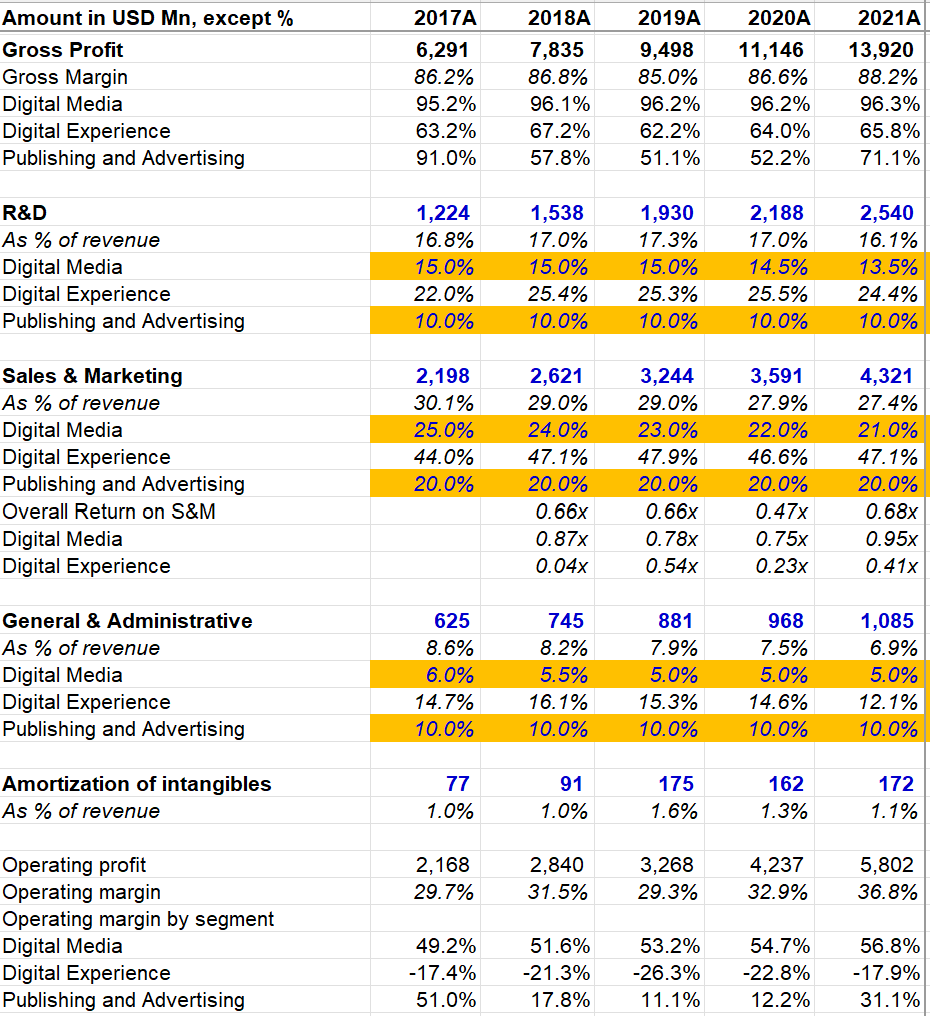

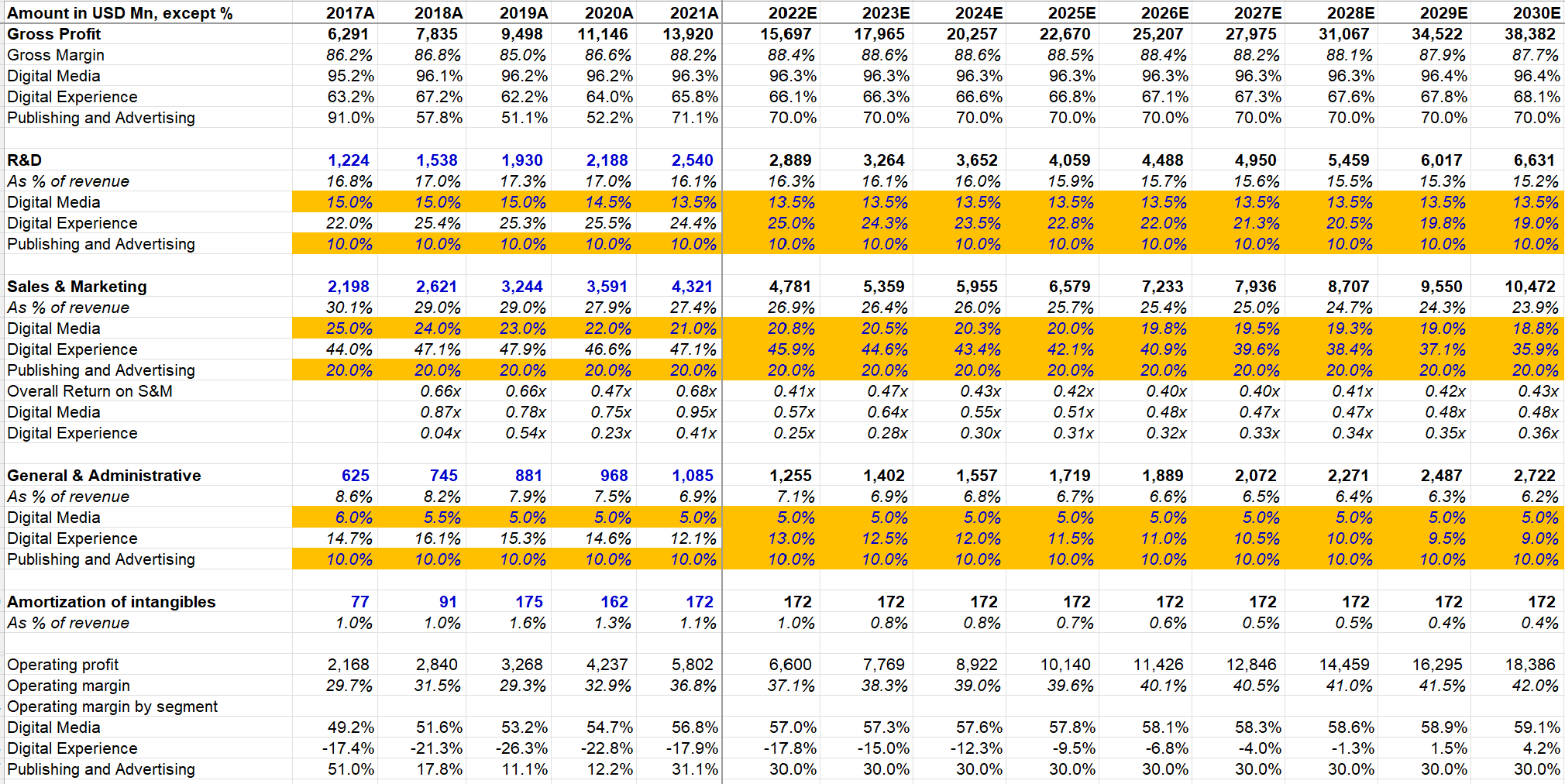

Adobe’s gross margin hovered between 85%-88% in the last five years. However, while Digital Media posted an incredible ~95-96% Gross Margin in the last 5 years, Digital Experience’s Gross Margin hovered around low-to-mid 60s. Since Salesforce is generally considered a close comp for the Digital Experience segment and Salesforce posted mid-70s gross margin in the last five years, it may give a good indication what long-term scaled gross margin can potentially be in Digital Experience.

The rest of the cost structure is a little tricky, but I made an attempt to segregate the margin of Digital Media and Digital Experience. Again, readers should remember that these are my estimates and actual numbers may differ from my estimates.

R&D as % of overall sales hovered around ~16-17% in the last five years. Most R&D in Digital Media is likely to be maintenance and I assumed ~13-15% of Digital Media revenue is spent on R&D. The implied R&D expense as % of Digital Experience revenue came out to be mid-20s. Salesforce’s R&D as % of revenue was ~17% last year, but Salesforce’s topline is ~7x the size of Digital Experience’s topline and hence it is likely that Salesforce’s R&D has better scale. Nonetheless, it is possible that Digital Media’s R&D is a little higher and Digital Experience’s R&D is little lower than assumed.

What about Sales & Marketing (S&M)? If your product has become verb (Photoshop) or de-facto file standard in the digital world (Acrobat PDF), I imagine most of Adobe’s Digital Media business almost sells itself at this point, especially individual consumers and SMB segment. Enterprise customers definitely require more sales effort. But given the self-serve nature of consumers and SMB segments, my guess is Digital Media’s S&M spending is much lower compared to the overall number reported by Adobe. While Adobe reported S&M as % of revenue in the high 20s, I assumed Digital Media segment spent mid-to-low 20s of its revenue in S&M. The implied S&M spending as % of revenue for Digital Experience came out to be in the mid-40s. While at first glance that may seem too high, looking at Salesforce which averaged 45.5% S&M as % of sales in the last three years, the number seems quite likely (or potentially conservative given the scale difference between the two companies).

When I added it all up, I came to the inference that Digital Media likely generates more than 100% of Adobe’s operating profit and the Digital Experience segment is likely to be run at an operating loss. Even Salesforce reported ~1-4% GAAP EBIT margin in 2016-2022. At 15% of Salesforce’s size, it is perhaps not so outlandish after all to think Digital Experience segment may have -5% or worse operating margin. For context, when Salesforce had $4 Bn revenue in 2013, it had -15% EBIT margin. Considering SBC for R&D and S&M professionals in today’s tech industry, it would not surprise me for Adobe to have worse margin than Salesforce at comparable topline.

Section 2 Total Addressable Market

Let me discuss TAM for Digital Media and Digital Experience separately.

Digital Media

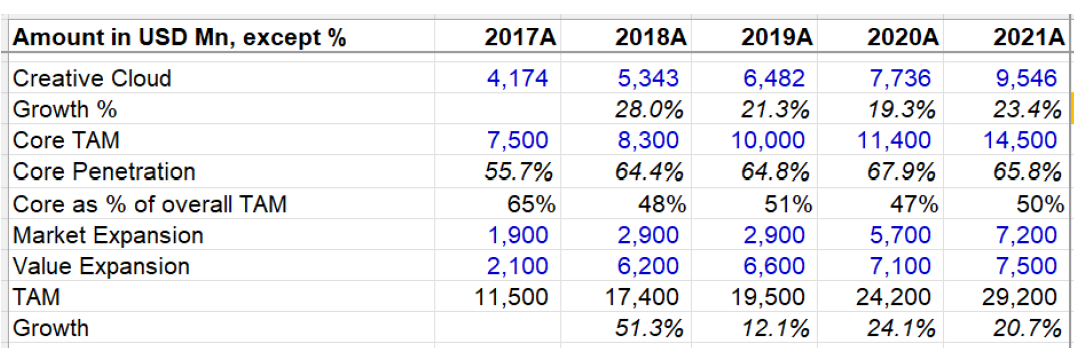

Creative Cloud: Up until November 2019 Analyst Day, Adobe used to breakdown the overall Creative Cloud TAM in three sub-categories: Core, Market Expansion, and Value Expansion. Core TAM is driven by growth of creative professionals, conversion from piracy, migration from perpetual licensing to subscription, free-to-paid conversion, SMB/enterprise seat expansion etc. Market expansion happened via broader interest among consumers on creativity tools, thanks to the rise of social media as well as the introduction of next generation apps such as Adobe XD, Adobe Express (formerly known as Spark), Adobe Scan etc. Finally, Value expansion happened by document cloud related services being integrated with creative cloud such as Adobe Sign.

Adobe used to report its own estimated TAM three year into the future on Analyst Meetings. For example, in 2018, they mentioned estimated TAM in 2021 to be $29 Bn for Creative Cloud, of which $14.5 Bn was identified as Core, $7.2 Bn as Market Expansion, and the rest $7.5 Bn as Value Expansion. If we ignore Market and Value Expansion estimates to just focus on Core TAM to have a relatively conservative estimate on TAM, Adobe’s penetration was consistently in the mid-60s in the last four years. When I was working for a fund back in 2019-20, I once attended a call with an expert who used to be part of the team responsible for estimating Adobe’s TAM. He provided a bit more context on the core TAM. He felt Adobe’s penetration on its core customer base i.e. Creative Professionals may even be close to 100% in the developed market and any growth in developed market basically needs to come from labor growth in Creative professional and exercise of potential pricing power. In the developing world, piracy is still a concern and subscriber growth may have a longer runway as subscription plans continue to lower the barrier and encourage international subscribers to become paying subscribers. Please note that Adobe’s pricing of creative cloud software, by and large, is uniform across geographies, so as long as Adobe can drive subscriber growth in any country, it will enjoy similar economics. One takeaway from the call was even though he felt Adobe over time became more aggressive in its TAM estimates, Adobe’s results also surprised itself on their more “internal TAM” estimates. Adobe itself likely didn’t quite imagine in 2016 that Creative Cloud revenue would be getting near $10 Bn without exercising much of pricing power.

Adobe on its 2021 Analyst Meeting shared their new TAM estimates for creative cloud in 2024 which expanded from $41 Bn in 2023 to $63 Bn. I wonder whether Adobe has learnt its lesson from previously conservative estimates a little too much. Adobe now thinks there will be 68 Mn Creative Pros and ~900 Mn “Communicators” (who are students, marketers, knowledge workers etc.) who size up to $25 Bn and $31 Bn TAM respectively. My sense is Adobe has effectively a monopoly in the Creative Professionals market, but their position in “Communicators” and “Consumers” segment, relatively speaking, is relatively weaker. If we completely ignore “Communicators” and “Consumers” segment (or Market/Value expansion as per the previous terminologies), that’s perhaps too conservative. The truth is somewhere in between. If we take Core TAM and assume half of Market and Value expansion TAM to be serviceable by Adobe, Adobe is currently ~50% penetrated.

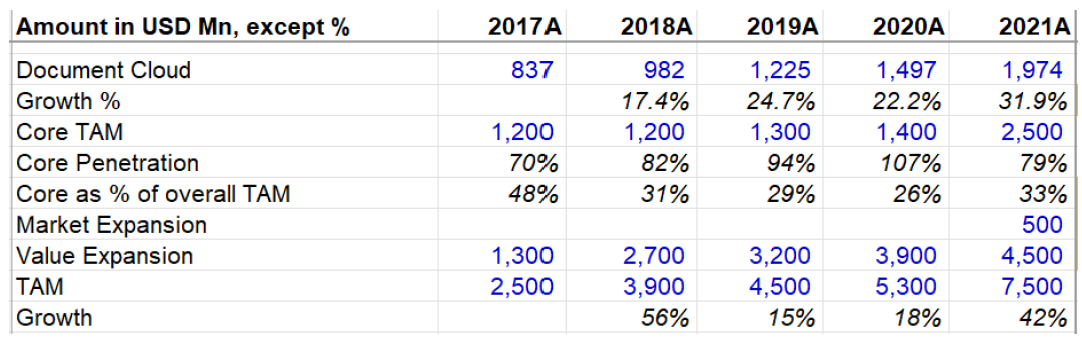

Document Cloud: Just as for Creative Cloud, Adobe used to report its estimates for Document Cloud in three sub-categories: core, market expansion, and value expansion. Core TAM has been driven by the growth of PDF, conversion from piracy, migration to subscription, conversion from free-to-paid, the rise of digital document market, knowledge worker expansion, international growth etc. Value Expansion is largely driven by the migration from paper to digital e-signatures, and document intelligence services such as Form fill and sign, document protection etc. Adobe Scan and Adobe Sign boosted the “Market Expansion”. Using similar method that we used for Creative Cloud i.e. assuming the whole Document Cloud revenue assigned to Core TAM, we can see core penetration increased from ~70% in 2017 to ~80% in 2021. The fact that it was even 107% in 2020 clearly indicates the flawed nature of our assumption here. At least for Document Cloud, Market and Value expansions are pretty real and much clearer revenue opportunities than perhaps Creative Cloud is. Thanks to the pandemic, e-Signature has certainly become a powerful secular theme and Adobe’s increasing focus on that theme indicates material market opportunity for them in this segment.

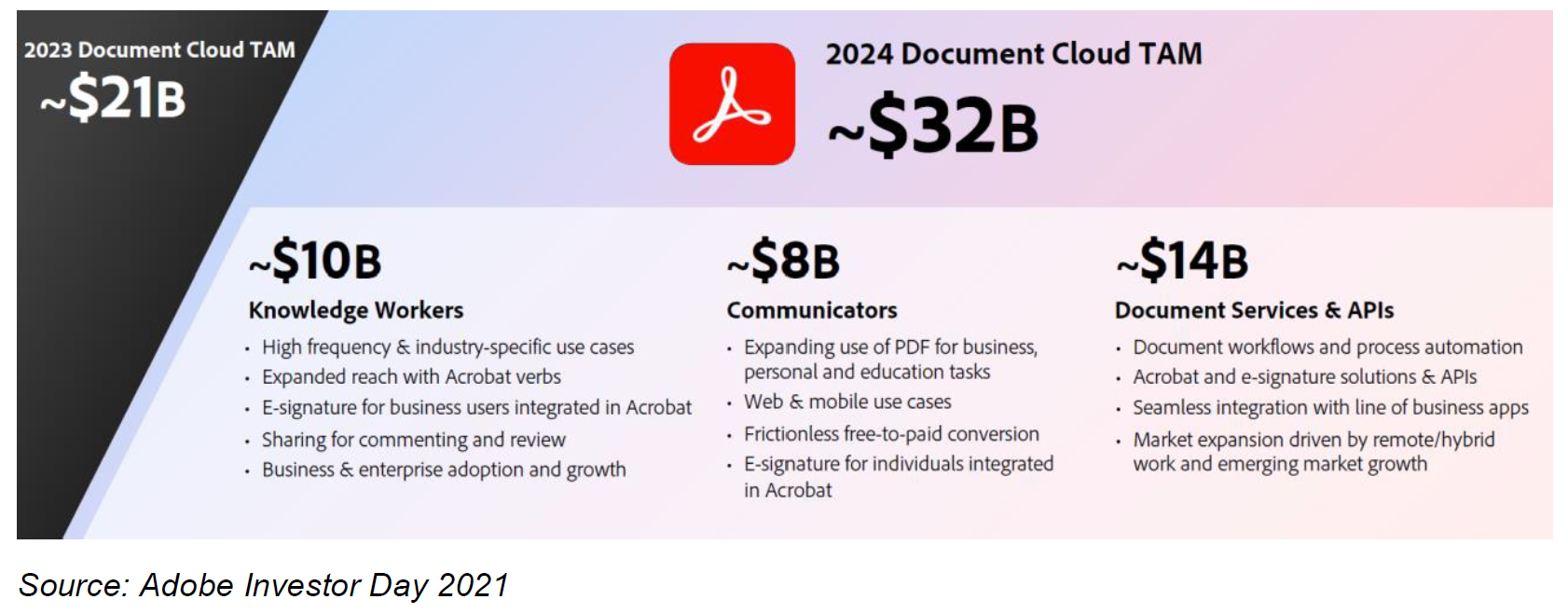

In 2021 Analyst meeting, Adobe significantly expanded its TAM from $7.5 Bn in 2021 to $13 Bn in 2022, $21 Bn in 2023, and $32 Bn in 2024. It is likely that Adobe’s TAM numbers has become too aggressive and hence less meaningful compared to the estimates it shared before. Given the investors’ generosity to massive TAM and narrative premium in the last couple of years, Adobe management may have been tempted to provide such lofty numbers.

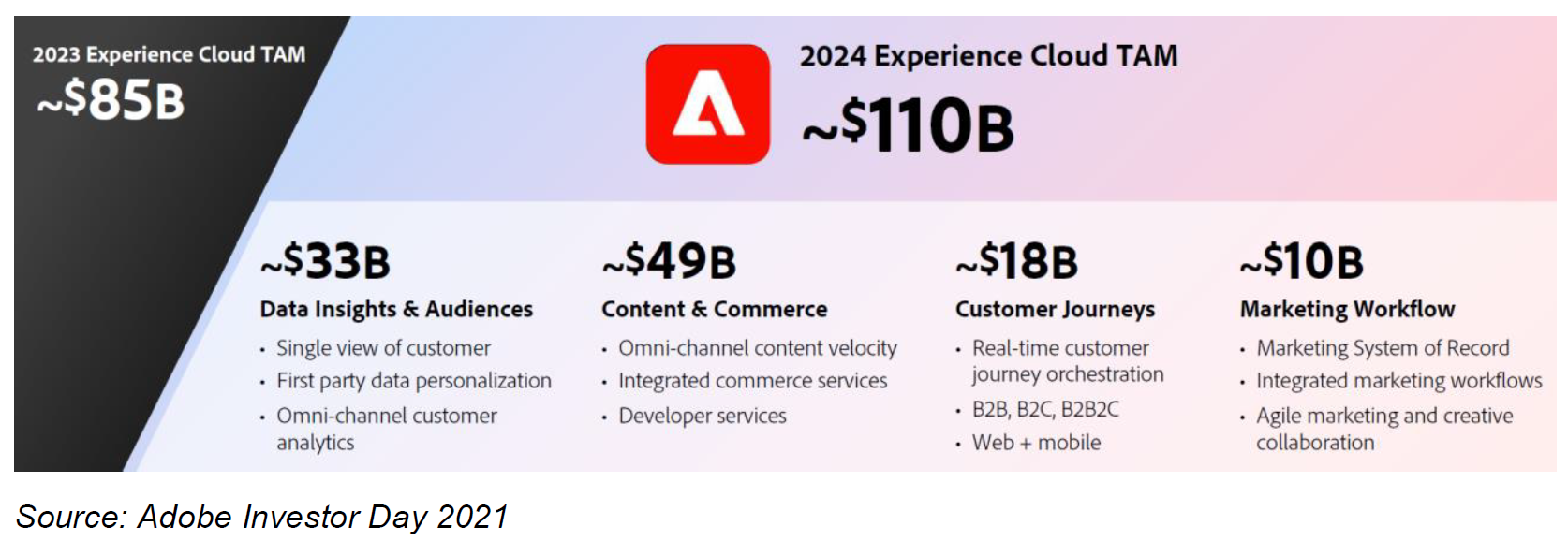

Digital Experience: Given the number of acquisitions Adobe made in this segment over the years, it is difficult to assess Adobe’s prior TAM estimates on Digital Experience. On the most recent investor day, Adobe estimated Experience Cloud’ TAM to increase from $85 Bn in 2023 to $110 Bn in 2024 which consists of Data Insights & Audiences ($33 Bn), Content & Commerce ($49 Bn), Customer Journeys ($18 Bn), and Marketing Workflow ($10 Bn).

Now that we have a sense of the size of the opportunity, let’s get into question of competitive dynamics.

Section 3 Competitive Dynamics

The competitive dynamics are somewhat different in the three segments Adobe operates. While it enjoys more of a monopoly in Creative Cloud, Document Cloud is bit of a duopoly and Experience Cloud is more oligopolistic in nature.

Considering the outsized importance of Creative Cloud for Adobe, I will primarily focus on Creative Cloud’s competitive dynamics, and briefly touch on Document Cloud and Experience Cloud’s competitive dynamics.

Creative Cloud

To understand the power or competitive advantages of any monopoly, it’s usually a good idea to study any prior case, court ruling, or FTC complaint alleging monopolistic behavior of a company. I did find a case from 2012: “Free Freehand Corp. v. Adobe Systems Inc.” In 2005, Adobe acquired Macromedia for $3.4 Bn which included assets such as Dreamweaver, Fireworks, Flash, FreeHand etc. FreeHand was a professional vector graphic illustration software and used to compete against Illustrator. Following the Macromedia acquisition, plaintiff alleged Adobe ended up having 100% share of professional vector graphic illustration software in the Mac OS Market and 80% in the Windows OS market. Let me quote some excerpts from the case to explain Adobe’s competitive advantage in Creative Cloud segment, and even though this case was only directed at Illustrator, a lot of these arguments may apply for the Creative Cloud segment:

“Marketing a technically comparable or even an improved software program would be difficult, time consuming, and unlikely because of network externalities associated with the current competitors' extensive installed user bases.”

“any new software product would have to simultaneously overcome a second network effect in the commercial printer software market. Commercial printers have their own software, which needs to be compatible with the files the designer sends to be printed. Commercial printers generally accept only Adobe, FreeHand, and, to a lesser extent, Corel files. Designers who want to print commercially cannot use file types that commercial printers cannot accept.”

“Adobe's bundling of Illustrator constitutes a significant entry barrier by limiting the ability of potential rival professional software manufacturers to enter the market without a full array of graphics software.”

“Plaintiffs allege that since acquiring FreeHand, Adobe has continually and significantly increased the price of Illustrator. In 2004, prior to the acquisition, the price for Illustrator was $399. In 2005, presumably after the merger, Adobe raised the price of Illustrator to $499. In 2008, Adobe released a new version of Illustrator and again raised the price of Illustrator to $599.”

It is interesting that while Adobe raised price for Illustrator by ~50% from 2004 to 2008, Creative Cloud’s prices have gone up by ~10% (individual subscription for the whole Creative Cloud apps) over the last 10 years. Why is that? I guess there are multiple factors at play here. On one hand, following the switch to subscription plan, Adobe was perhaps positively surprised how a large part of the market remained untapped for a long time, and with the rise of digital content, Adobe might have chosen a conscious path to grow the installed base instead of maximizing the price for subscription today. Therefore, Adobe perhaps still has a big lever to pull if they ever feel they are reaching near the full penetration level of this larger market of creative professionals/enthusiasts in the next few years. While prices have risen just 10% in the last 10 years, it is perhaps very much possible that prices may rise 50% in the next 10 years. Short-term high inflation may, in fact, give companies such Adobe a very good excuse to raise price and enjoy the benefit of higher price over the long-term even when inflation comes down later. The power of zero marginal cost in software can, of course, only be fully enjoyed as long as you can protect your turf. On the other hand, some skeptics may argue that it will be much more difficult for Adobe to extract supernormal profit from its Creative Cloud software given the rise of compelling alternatives. This tweet, in fact, shows how you can find Adobe alternative products for every app Adobe has.

I came across a good YouTube video titled “Why do I pay Adobe $10k a year” which explored whether his team could build the YouTube video without using any Adobe product. They could, but in the end of the video, he explained why he still prefers Adobe:

“First up, the size of their app library is unparalleled, whether you’re creating videos with effects, audio, image, documents, webpages, there’s an app for that. And in today’s age where many creators are one-man/woman show…a single ecosystem is very attractive, even if its bugs occasionally make the biblical plague of locusts look like not that big of a deal. Second up is inter-compatibility. For better or worse, pretty much everybody else uses Adobe and nobody likes to be that guy who sends the weird file formats that nobody else can open. The thing is you don’t get to pick who you’re doing business with and not everybody out there in the great wider world has the tech savvy or the willingness to deal with your snowflake file format. And guys, it’s creative industry. Collaboration is a big part of it. Finally, the way that Adobe’s app dynamically link with each other drastically cuts down on the time that you would otherwise spend saving, exporting, editing, and then importing files between your apps. So I asked our team how close they think we could get to creative suite levels of efficiency and the highest number that I got back was as much as 90%. On the face of it, that sounds pretty good. But let’s do some napkin math here. The average video editor in the US makes $29/hr. We’ve got 7 of those, so assuming we were paying those rates, our editing staff would cost us ~$420k/year (29740*52; 40 hours/week and 52 weeks/year). If we were to slash their productivity by 10% by taking away their preferred software as a cost-savings measure, we would need to either cut our 17 videos per week production schedule, costing the company revenue, or we would need to hire to cover that difference, costing the company >$40k/year. Plus, the extra space we’d need in the building, extra editing workstation…I think you see where I’m going with this. I mean, we’re not saying that using Vegas or Resolve or even some of the awesome, free editing tools out there, like HitFilm Express aren’t gonna work for you. We’re just saying that even if it does feel a little bit like Stockholm Syndrome, Adobe continues to be our best option.”

While that seems a compelling testimonial for Adobe’s durability in Creative Cloud, there are potential area of concerns. Kevin Kwok, former Investor at Greylock Partners, wrote two very interesting pieces which explored the potential competition for Adobe: a) Why Figma Wins, b) How to Eat an Elephant, One Atomic Concept at a Time. Both are long but very interesting reads, and if you are Adobe shareholder or just currently doing research on Adobe, I strongly encourage you to read those pieces. Please note Kwok worked on Greylock’s investment in Figma.

So, how can startups such as Figma, Canva, and Sketch challenge a monopoly? Kwok explained:

“Changing customer needs are the largest source of entropy in markets. When customer needs rapidly change, there is less advantage in being an incumbent. Instead, legacy companies are left with all the overhead and a product that no longer is what customers want.

There are many causes of changing customer needs. Often there are new and growing segments of customers with different use cases. Existing products may work for them, but they aren’t ideal. The features they care about and how they value them are very different from the customers the legacy company is used to. Companies resist changing core parts of their product for every new use case since it’s costly in work, money, and attention. But every once in a while, what was once a small use case grows into one large enough to support its own company.”

Before going any further, let me borrow from Kwok to introduce Figma, Sketch, and Canva to explain how they are different from each other in building the picks and shovels for creativity:

“Similar companies often have slightly different atomic concepts that end up making them meaningfully distinct. Photoshop is focused on pixels and images. Its focus is on editing images and pictures. And its functions operate by transforming them on a pixel level.

Illustrator is similar, but it operates on vectors, not pixels. This is a higher level abstraction. Neither is better or worse, they are just more suited to different use cases. Photoshop is better for modifying images, while illustrator is built for designs where scale-free vectors are best.

Sketch, like Illustrator, is vector based. But is designed for building digital products which means things like operating at a project level. It is not individual designs, but crafting entire products and user interfaces—and the needs for repeatability and consistency inherent to that.

Figma builds on Sketch’s approach, but also includes a greater focus on not just projects but the entire collaborative process as the relevant scope. Similarly, it also treats higher level abstractions like plugins, community, and more as equally important concepts.

Canva is similar to Photoshop and Illustrator, but its users aren’t designers who care about low level tools. Instead Canva’s core atomic concepts are around the different templates and components to help them easily accomplish the job they are doing. And the designs they are working on are not quite at the project level of making a digital product. They are canvases that include images and design.”

On his piece “Why Figma Wins”, Kwok elaborated how Figma’s approach was unique:

“The core insight of Figma is that design is larger than just designers. Design is all of the conversations between designers and PMs about what to build. It is the mocks and prototypes and the feedback on them. It is the handoff of specs and assets to engineers and how easy it is for them to implement them. Building for this entire process doesn’t take away the importance of designers—it gives them a seat at the table for the core decisions a company makes.

I used to be confused by the Figma’s team consistent framing of Figma as browser-first. What was the distinction between this and cloud-first? Over time I’ve come to see how important this distinction has been. When many creative tools companies talk about the cloud, they seem to view it as an amorphous place that they store files. But the fundamental user experience of creating in their products is done via a standalone app on the desktop. Figma is browser-first, which was made possible (and more importantly performant) by their understanding and usage of new technologies like WebGL, Operational Transforms, and CRDTs.

From a user’s perspective, there are no files and no syncing that needs to be done with others editing a design. The actual experience of designing in Figma is native to the internet. Even today, competitors often talk about cloud, but are torn over how much of the experience to port over to the internet. Hint: “all of it” is the correct answer that they all eventually will converge on.

Designers loved Figma and this drew initial distribution. And with features like team libraries, designers have incentive to pull in other designers on their team into Figma. But a tool designers love, while a prerequisite for success, does not fully capture the root of Figma’s traction so far. While Figma has been building the ideal tool for designers, they’ve actually built something more important: a way for non-designers to be involved in the design process.

Historically it has been very difficult for non-designers to be involved during the design process. If PMs, engineers, or even the CEO wanted to be involved, there were many logistical frictions. If they wanted the full designs, the designer would need to send them the current file. They’d then need to not only download it, but also make sure they had the right Adobe product or Sketch installed on their computer—costly tools that were hard to justify for those who didn’t design regularly. And these tools were large, slow, specialized programs that were unwieldy for those not familiar with using them. It was hard to navigate a project without a designer to walk you through it. Comments were done out of band in separate emails. Even worse, if a designer made an update before viewers had finished looking at the file, the file would be out of date—without the viewer being aware.

The experience was just as bad for designers. Even if they wanted their PMs and engineers to give feedback, they’d need to handhold them through the process. Designers would have to export the designs into images, send the screenshot, and later figure out how to translate the feedback into changes in the actual design. The feedback loop was so slow that they’d need to pause their process while waiting for feedback.

Of course, what really happened is that most of the time non-designers just didn’t engage as much with the design process. The pain of reviewing designs wasn’t the primary problem, but there was enough friction that reviewing often never happened.

Figma fixed this.

Sharing designs with Figma is as easy as sending a link. Anyone can open it directly in their browser. It’s as easy as going to a website, because…well…it literally is going to a website.”

Canva, on the other hand, perhaps attacks Adobe’s “Value Expansion” and “Market Expansion” TAMs. Again, from Kwok’s piece:

“Canva’s distribution is driven in large part by their SEO. Unsurprisingly, the very same use cases people use Canva for are what people looking for design tools want to do and search Google for. With their product and templates built around these use cases, it’s easy for Canva to expose that externally and have lots of templates and examples ready to go for potential new users looking to do a specific design. Everything about their user acquisition and onboarding is built around the specific use cases people have and Canva’s atomic concepts. They are built around the functional workflows people have, whether that’s making a Twitter background photo, a wedding invite, or a keynote presentation. And Canva is committed to making that as easy as possible.

As they’ve grown, Canva has expanded their ecosystem by creating marketplaces and communities around templates, layouts, fonts, and more. Most users don’t want to build from scratch. With Canva’s marketplaces there is an entire ecosystem of pre-built components they can use, both free and paid.

Canva having this strong ecosystem of add-ons is very powerful. Add-ons allow Canva to address the huge scale and varied needs of all its customers, far more that no one company could ever do on its own. This makes it possible for each customer to use Canva in a way that will be personalized for exactly the use case and aesthetic they care about.”

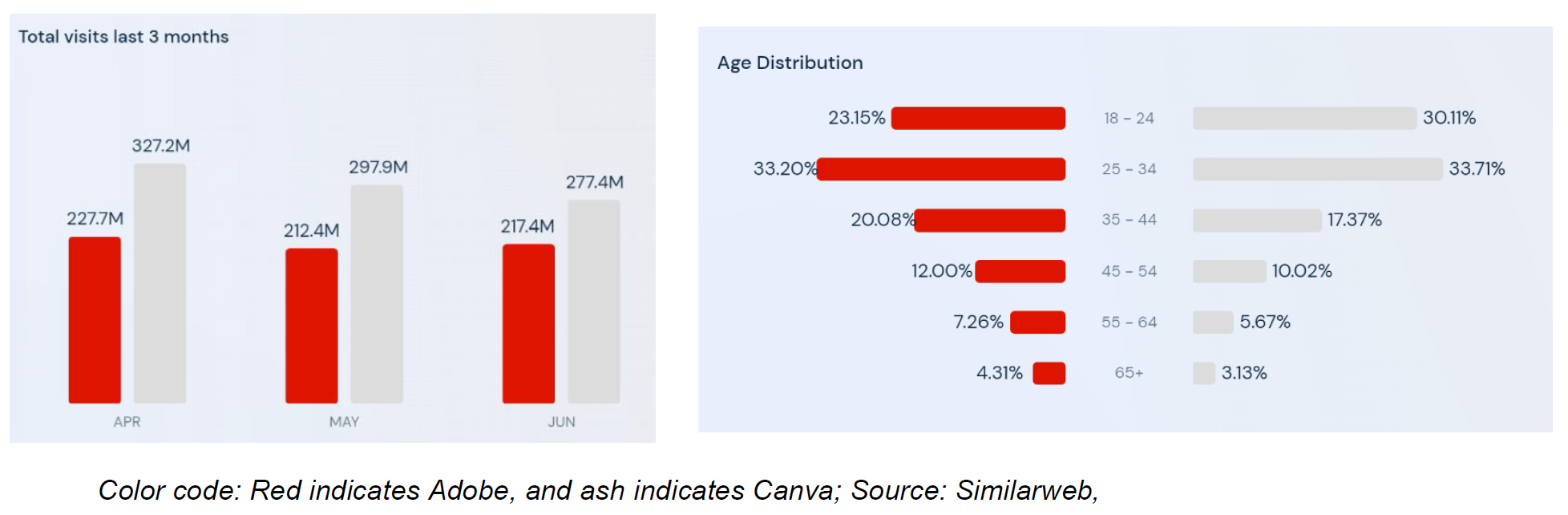

For context, Canva already receives higher traffic than Adobe. While the traffic is largely similar in the US, the traffic delta is significantly higher in the international market. Perhaps not surprisingly, younger people i.e. 18-24 year olds are some of the dominant users of Canva. And it’s not just all SEO game since as per Similarweb data, ~75% of the traffic to Canva is direct vs ~50% for Adobe.

While Kwok’s pieces do a pretty good job at understanding the threat Figma and Canva may pose to Adobe in the long-term, let’s discuss some numbers. Obviously, these are private companies, so keep that limitation in mind.

Figma was launched in 2016. As per a Forbes piece, Figma’s ARR in 2021 was expected to more than double from $75 mn in 2020. Let’s say it was $150 mn ARR in 2021. While the growth % seems impressive, Adobe’s absolute dollar growth in 2021 was ~12x the size of Figma’s estimated topline in 2021. In June 2021, Figma raised $200 million at $10 Bn valuation, so it was valued ~67x 2021 ARR. For context, it took Adobe ~8 years to exceed $150 Mn revenue in the ‘80s which Figma took 5 years to reach. I’m obviously not comparing, and frankly given the size of the market back then (vs now), it makes me think Adobe’s numbers were more impressive (and vice versa for Figma). And while Adobe was growing profitably almost from the very beginning, I don’t think that’s the case for Figma. Nonetheless, I do not think Figma should be taken lightly as a potential threat to Adobe. One of the perhaps most concerning thing I came across is many up and coming designers feel deep affinity to Figma and sort of have this “Figma or bust” mentality. For example, here's what one Senior Design Manager at Dropbox said in an expert call: “I would say that using Figma as a tool is something that I prioritized in my own job search. If a company doesn't use Figma and maybe isn't invested on moving over to Figma, I would likely not work there. It has become that much of a standard in our practice.” This sort of risk may take time to manifest in numbers, but if it is a braoder trend among young and talented designers, that is a serious concern for Adobe.

How about Canva? It was founded in 2012 and launched its first product in 2013. Canva is supposedly profitable since 2017 when it had less than $50 Mn revenue. Just based on numbers, Canva actually appears to be more impressive than Figma. Canva posted sales of $86 Mn in 2018, $291 Mn in 2019, $500 Mn in 2020, and $1 Bn in 2021. For context, Adobe took 17 years to reach $1 Bn revenue whereas Canva took half the time to get there. Again, I’m not comparing since TAM is just so much larger today, but Canva seems to be growing at a breathtaking pace.

Now that both public and private tech market is taking a breather, it may be challenging few quarters/years ahead for unprofitable private tech companies to raise funds or attract topnotch talent vs the cash flow rich incumbents such as Adobe. If Adobe ends up acquiring Figma or Sketch in the scenario that the tech winter lasts longer than we may think today, it will help de-risk Adobe’s creative cloud’s terminal value. I do expect both Canva and Figma to encroach into Adobe’s territory much more aggressively in the next 10 years if they can withstand the current dicey environment. As they evolve more and more from feature to product to platform to full blown ecosystem with a range of products to match Adobe’s capabilities, Adobe’s monopoly may be eroded. It seems difficult to predict now, but it’s something that needs to closely watched, especially given that Creative Cloud likely generates almost all of Adobe’s FCF.

Before wrapping up the competitive dynamics in Creative Cloud, let me mention one more risk and one opportunity.

A big opportunity could be the rise of Metaverse. Adobe (and others) is in the business of providing picks and shovels for creativity and while the range of outcomes is pretty wide for companies building the platform for Metaverse, Adobe (and others) is likely to be in a privileged position to enjoy mostly the upside of such transition to new computing platform without the risk to the downside. It’s possible that tools for digital creativity may maintain its momentum and can even accelerate further in this decade; the pie may become so large that the debate among Figma, Canva, or Adobe may prove to be irrelevant.

A potential risk could be the prevalence of text-to-image GenAI tools such as Dall-E that creates realistic images and art from a description in natural language. If anyone can just create compelling images based on word prompts, I wonder whether that would act as headwinds for creativity tools, especially for creativity enthusiasts market. Meta, Google, and perhaps others are working/have already launched similar tools. It remains to be seen how such innovation would affect Adobe.

Document Cloud

Adobe faces different competitors depending on the segment of the market. At the low end i.e. sole proprietors or SMBs, there are more competitions; it’s not just DocuSign, but HelloSign (acquired by Dropbox for $230 Mn in 2019) and PandaDoc (valued $1 Bn in their last round of fund raising in Sep’21) are competitors in the low end of the market. However, in the mid to enterprise market, Adobe and DocuSign operate in largely a duopoly. DocuSign seems to have owned the e-Signature market and even if the enterprise market is mostly duopoly, DocuSign is a much larger player than Adobe in that segment. While both Adobe’s Document Cloud and DocuSign had ~$2 Bn revenue in 2021, Adobe’s Document Cloud revenue also includes revenue generated from its legacy Acrobat PDF business. Therefore, in the purely e-Signature market, DocuSign is a clear leader.

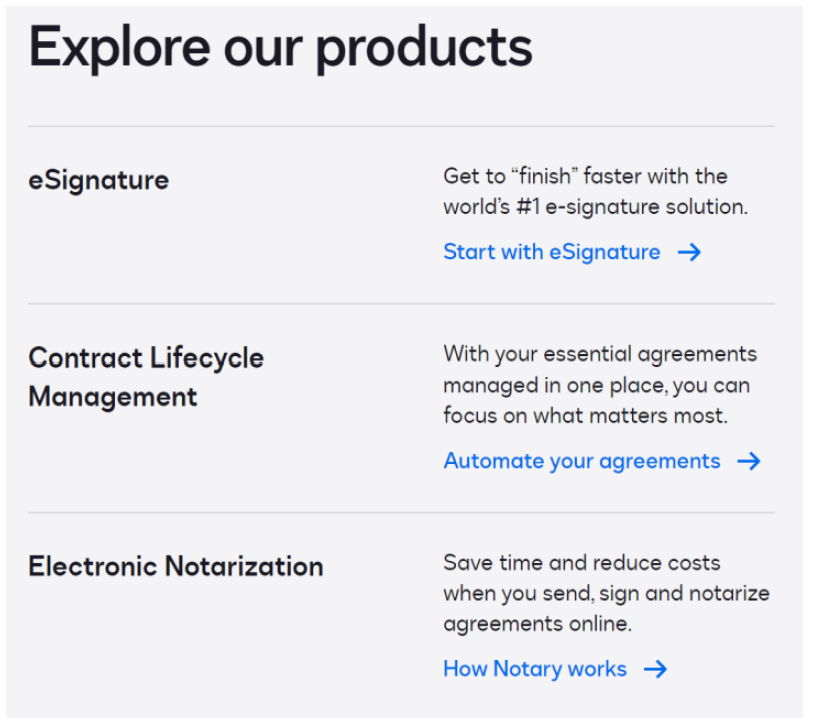

Even though DocuSign’s revenue increased 4x in the last 4 years (vs ~2.4x for Adobe Document Cloud), there is a growing consensus that e-Signature itself is a commodity business. DocuSign is a premium product, and it can be challenging to justify the premium unless they become more than an e-Signature solution. As a result, DocuSign is more focused on establishing “Agreement Cloud” which includes eSignature, contract lifecycle management, and electronic notarization. Instead of being a point solution, DocuSign is trying to build a platform business. When companies have to incorporate automation and workflows into their process, Adobe and DocuSign stand out.

Some investors I spoke with mentioned to me that it is frustrating to see DocuSign leading this market given Adobe’s absolute dominance on PDF, and they should have dominated the eSignature market as well. It does seem, however, that Adobe’s Document Cloud is catching up especially when DocuSign is dealing with post-pandemic hangover as DocuSign’s CEO just recently resigned in June 2022.

One potential risk for both DocuSign and Adobe is if vertical software companies focused in specific industries (manufacturing, banking, legal etc.) embed eSignature solutions in their broader workflow, that may pose threat to long-term growth. Such embeds can allow vertical software companies to control the user experience better and perhaps can make it a more cost-effective solution for specific industries. Adobe itself has been using its enterprise sales team to cross-sell broad range of products. While product is perhaps of paramount importance in consumer software, sales and distribution may be more important to build durability in enterprise software.

Experience Cloud: Salesforce is often talked about as the closest competitor of Adobe’s Experience or Marketing Cloud. Given the number of acquisitions Adobe made to build the Experience Cloud and my own lack of understanding of Salesforce, it is challenging for me to opine on the competitive dynamics of this segment. As I plan on covering Salesforce in December this year, I hope to gain better understanding on the broader landscape.

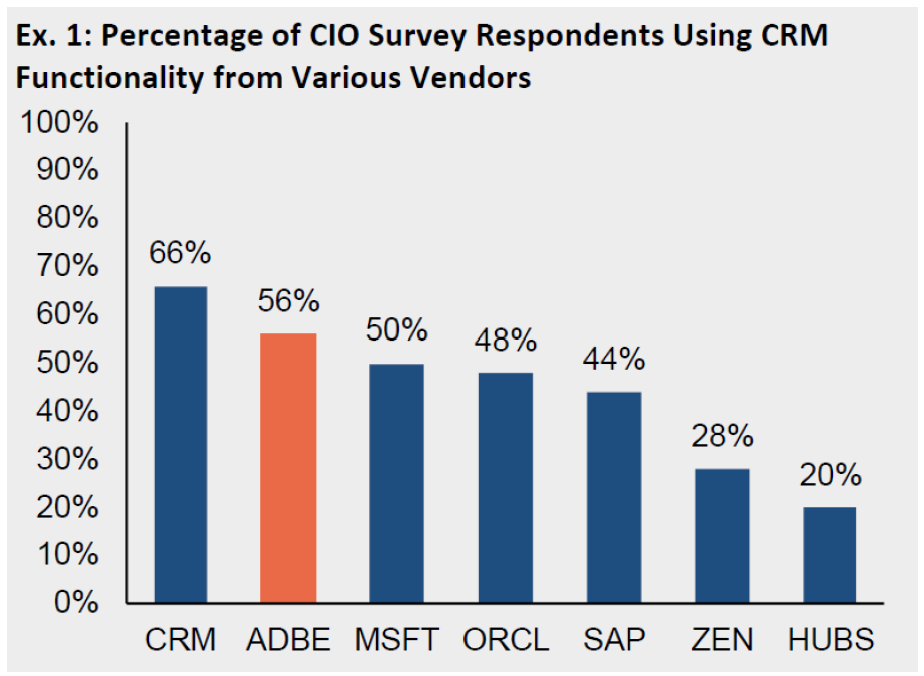

However, when I spoke with a few investors, my sense is that Digital Experience is oligopolistic and while Salesforce and Adobe are competitors in this segment, they are also often used simultaneously in an organization. For example, Wolfe Research did a survey among CIOs in April 2021 in which 66% of CIOs mentioned their companies use CRM from Salesforce whereas 56% mentioned Adobe, followed by 50% for Microsoft and 48% for Oracle. Such data point is evidence that multiple winners may be able to co-exist in this industry.

Section 4: Capital allocation and Incentives

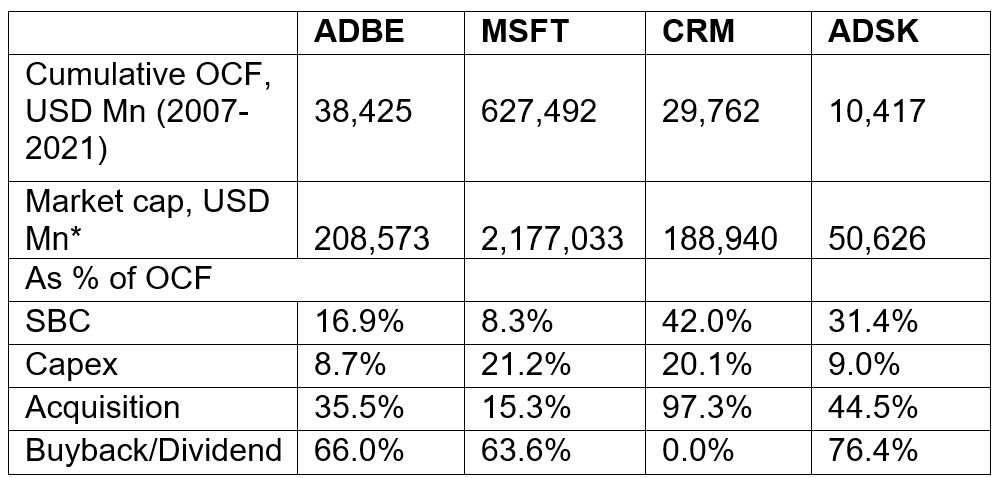

Let’s start with capital allocation. Since Shantanu Narayen became CEO in 2007, I wanted to look at Adobe’s capital allocation history during his entire period. Considering the length of his tenure, it would give me a better sense of how Adobe likes to allocate capital over the course of the whole economic cycle. For reference, I have also shown some peer enterprise software companies who have been around for multiple decades: Microsoft (MSFT), Salesforce (CRM), and Autodesk (ADSK). Adobe generated a cumulative $38 Bn Operating Cash Flow (OCF) from 2007-2021, ~9% of which was spent in Capex, ~36% was in acquisition, and ~66% was spent in buyback or dividends. Please note that Stock Based Compensation (SBC) accounted for ~17% of the OCF.

Like Autodesk, Adobe is capital light business. Microsoft is obviously spending a lot on capex for Azure, but except for Salesforce, all of them spend majority of their operating cash flow on buying back stocks. Adobe and Autodesk are much more acquisitive than Microsoft and Salesforce again is bit extreme as Salesforce spends almost all of their operating cash flow to acquire new companies.

Given Adobe’s heavy spend on acquisitions, it is certainly a relevant question whether such acquisitions have proved to be prudent capital allocation. My sense from speaking with a few investors is shareholders are largely supportive of Adobe’s acquisitive strategy of building out the Digital Experience segment. Based on my margin assumptions that I discussed in section 1, it would not surprise me if Digital Experience segment were yet to post any profit in any single year. Therefore, while it theoretically perhaps makes sense to build Digital Experience segment given the oligopolistic nature of the industry and potentially higher LTV of its customers, it is still bit of an open question for me. I will probably have more answers on this question after doing a deep dive on Salesforce to understand the overall attractiveness of Digital Experience in the long run.

Beyond the economics and long-term profitability of Digital Experience, another question is whether management paid appropriate prices for the acquisitions. Again, it’s hard to answer this question with high conviction, but I somewhat lean towards the view management may have overpaid for some of these acquisitions. Let me briefly discuss two major acquisitions in Digital Experience in the last 5 years: Marketo, and Magento.

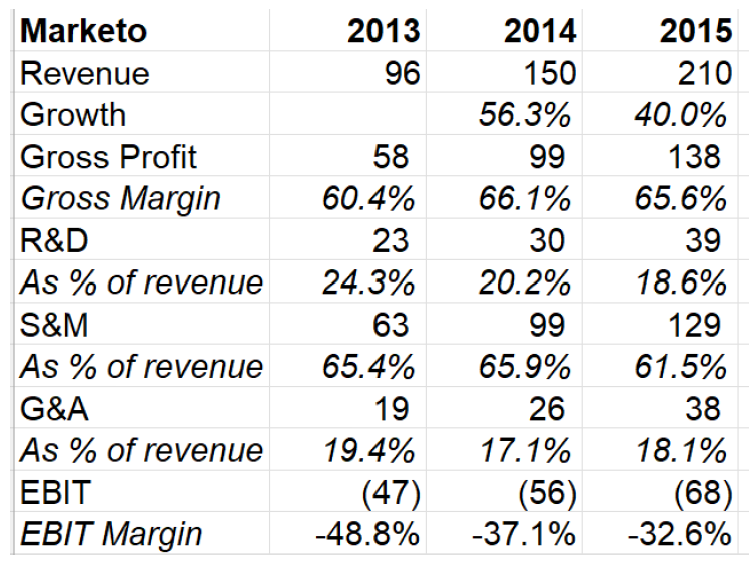

Marketo: Since Marketo went public in 2013, we have their financial statements till 2015 before Vista bought them for $1.8 Bn in 2016. Marketo’s top line grew by 40% in 2015; however, its operating margin was -33%. While operating margin markedly improved from -49% in 2013 to -33% in 2015, it was clearly far from ideal, and Vista perhaps wanted to streamline the operations to right size the cost structure a bit.

Just two years after Vista’s acquisition, Adobe bought Marketo for a whopping $4.75 Bn in 2018, giving Vista almost ~$2 Bn profit on this deal. Adobe clearly missed the opportunity of bidding for Marketo when it was lot cheaper in 2015. In the M&A call with the analysts, Adobe mentioned Marketo posted $320 Mn revenue in 2017 which imply 23.5% 2-year CAGR from its reported topline in 2015. Presumably, while the topline growth had slowed, operating margin supposedly improved (Adobe mentioned this in the call but didn’t explicitly disclose the numbers) in the meantime which perhaps allowed Vista to ask for the hefty multiple.

Let’s imagine a very optimistic case for Marketo. Assuming it grows at 20% CAGR from 2017-2027, it will reach $2 Bn topline in 2027. If we assume 70% gross margin, 15% R&D as % of sales, 35% S&M as % of sales, and 10% G&A as % of sales, it implies 10% GAAP EBIT margin or ~$200 Mn EBIT in 2027. If Adobe wants to generate ~10% IRR from its investment in Marketo, we need to assume ~60x EBIT multiple in 2027. I guess bulls probably believe in ~15-20% GAAP EBIT margin in the long run, but I think such margins are far from inevitable.

Magento: Unlike Marketo, Magento was never public, so we don’t have as much detailed financials. Founded in 2008, Magento was bought by eBay for $180 Mn in 2011. In 2015, eBay sold Magento for $200 Mn to Permira Funds. When Adobe acquired Magento in 2018, they mentioned Magento had ~$150 Mn annual revenue. Given Adobe paid $1.68 Bn for Magento, they paid ~11x LTM revenue for the deal. Shopify is a direct competitor of Magento, and it is perhaps not unfair to say that Magento is not poised to put up a decent fight against Shopify. At the time of the acquisition, Shopify had $760 Million LTM revenue and was trading at ~20x P/S multiple at that time. Shopify currently has ~$5 Bn LTM revenue and trading at ~10x LTM P/S today. My guess is the difference between Magento, and Shopify has grown further over time. If we assume $500 Mn revenue for Magento in 2021 and 5x multiple on that revenue, we get $2.5 Bn valuation today which implies ~10% IRR over 4-year period since acquisition. While that sounds decent, I am skeptical Magento will be a viable and high FCF generating business over the long term.

Overall, with the caveat of I’m still ramping up my learning on Digital Experience, I lean towards the opinion that Adobe may have overpaid for some (maybe most?) of these acquisitions. Given the high margin cash flows coming from Creative Cloud, management has hardly been faced with tough questions on the acquisitions they did or profitability of these acquisitions over the long term.

Having said that, Shantanu Narayen certainly did A+ job in migrating the business model from perpetual licensing to subscription model. As discussed in section 1, while the rationale for migration seems obvious in retrospect, it was quite courageous decision at that time. Moreover, it is hard not to appreciate any software company that’s been able to protect its monopoly (I’m using the term lightly) over multiple decades. The magic of zero marginal cost unfortunately also comes with the baggage of obsolescence risk in software much more than perhaps in other industries.

Although Narayen has been leading Adobe since 2007, he is still just 59 years old, so I wouldn’t be surprised if he continues to be CEO for the next 5 years.

In terms of incentives, annual performance is tracked with two broad metrics: a) Digital Media ARR and Bookings growth in Digital Experience, and b) GAAP revenue and non-GAAP EPS performance against operating plan targets. I would have preferred to see GAAP EPS since that would include SBC component into the management’s performance mix.

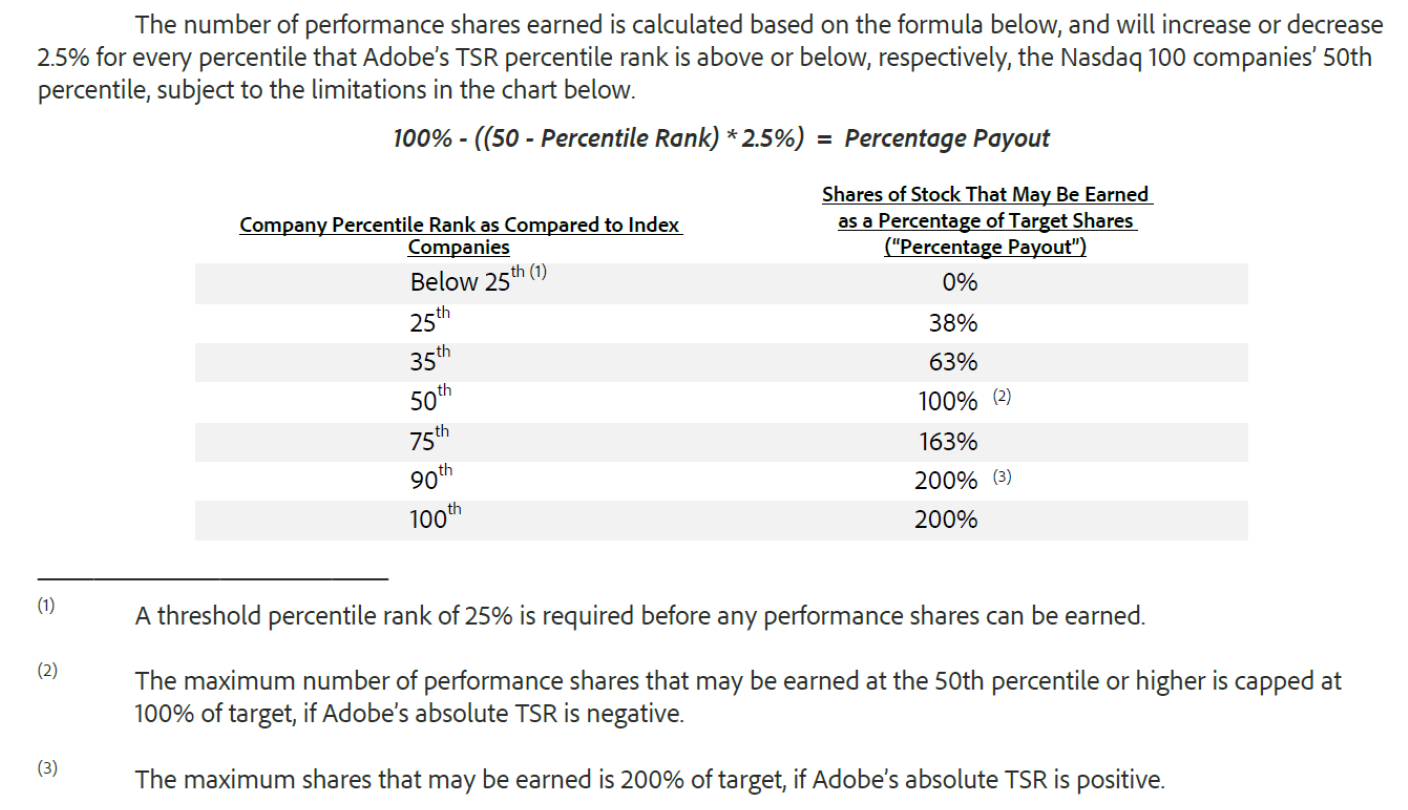

For long-term incentives, like Danaher, Adobe also follows a relative Total Shareholder Return (TSR) approach. While Danaher’s benchmark is S&P 500, Adobe’s benchmark is understandably NASDAQ 100. Again, similar to Danaher, if TSR is negative, the maximum payout is 100% even if relative TSR percentile is above 50 percentiles.

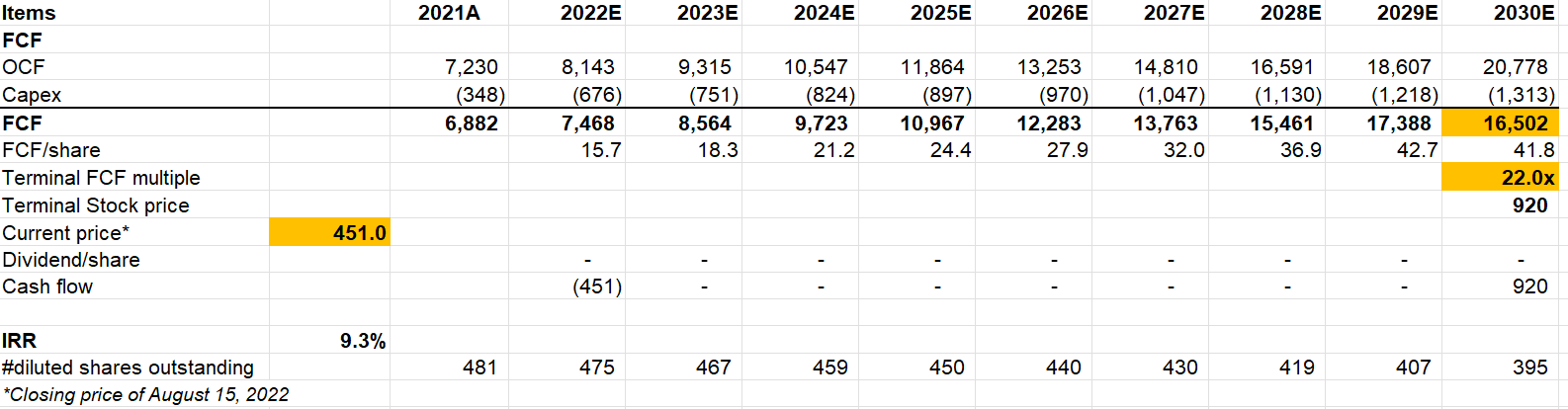

Section 5: Valuation and model assumptions

If you are reading my deep dive for the first time, I strongly encourage you to read my piece on “approach to valuation”. Please read it at least once so that you understand what I am trying to do here. I follow an “expectations investing” or reverse DCF approach as I try to figure out what I need to assume to generate a decent IRR from an investment which in this case is ~9%. Then I glance through the model and ask myself how comfortable I am with these assumptions. As always, I encourage you to download the model and build your own narrative and forecast as you see fit to come to your own conclusion. None of us have the crystal ball to forecast 5-10 years down the line, but it’s always helpful to figure out what we need to assume to generate a decent return.

Revenue Model

As explained before, Digital media has two sub-categories: Creative Cloud, and Document Cloud. My model implies Digital Media subscriber will increase from 24 mn estimated subscribers in 2021 to 48 mn in 2030. While the assumed pace of growth in percentage is lot slower compared to the past (i.e. estimated number of Digital Media subscribers increased from 11 mn in 2017 to 24 mn in 2021), the absolute number of new subscribers in the next 9 years is almost double the subscribers added in the last 4 years. This is probably indeed a good base case although I suspect the probability of posting 5-10 mn more subscribers in 2030 than assumed is lower than the probability posting 5-10 mn fewer subscribers. As I have discussed before, one potential lever to continue to post double digit or mid-teen revenue CAGR in Digital Media for this decade could be price increases. My model does imply revenue per estimated Digital Media subscriber to increase from $532 in 2021 to $645 in 2030. Price increases may come from a combination of adding new apps to Creative Cloud subscription as well as pure exercise of market power. Given the installed base, adding new apps and using that as “excuse” to increase price for Creative Cloud can allow Adobe to continue to post healthy topline growth even if subscriber numbers seem to hit a wall at some point. As you can imagine, maintaining the “monopoly” status is going to be key to be able to exercise such pricing power. Moreover, while I don’t expect Adobe to experience as much revenue volatility as it did in earlier recessions because of the earlier perpetual licensing model, there should be some impact in Adobe’s revenue during economic recession. Adobe may not be nearly as cyclical as advertising industry, but if your customers face the brunt of recession and stop hiring people, Adobe will in turn face similar headwinds. I don’t think my model captures such potential recessionary periods in the projection period.

Cost structure: As I discussed in Section 1, I have made some assumptions on Digital Media margins to calculate the implied margins for Digital Experience. Digital Media’s gross margin is assumed to be slightly above 90% and Digital experience’s gross margin is assumed to hover around mid-70s. R&D as % of revenue for Digital Media was assumed to be low-teens whereas Digital Experience’s R&D as % of revenue is assumed to gradually go down from mid-20s today to high teens/low 20s in 2030. S&M as % of revenue for Digital Media is modeled to be high teens whereas Digital Experience’s S&M as % of revenue is modeled to go down from mid 40s in 2021 to mid-30s in 2030. Overall, operating margin for Digital Media is modeled to increase from estimated 53.0% in 2021 to 54.8% in 2030 and Digital Experience’s operating margin is assumed to increase from -17.9% in 2021 to 4.2% in 2030, a whopping 22 percentage points expansion over the next 9 years. Again, as you can see, Adobe is expected to not only maintain their monopoly status in Digital Media but also make Digital Experience a profitable business in the long run.

Valuation: To generate ~9% IRR, I had to assume 22x FCF multiple in 2030. The multiple is not perhaps onerous if 10-year yield hovers around ~3% and Adobe posts the kind of numbers I have modeled. If in 2030 we find ourselves in a world where Adobe continues to firmly maintain their monopoly in Digital Media and the current crop of challengers such as Canva and Figma prove to be more of standalone products rather than large thriving platforms for creativity tools encroaching more and more into Adobe’s world, investors may be more generous than 22x FCF multiple in 2030 (again, with the caveat of rates). On the other hand, if Adobe’s monopoly gets eroded over the course of this decade, the multiple may be more depressed regardless of what the rates are at that time. Mr. Market is generally not very generous when a company priced like a monopoly finds itself in a competitive market.

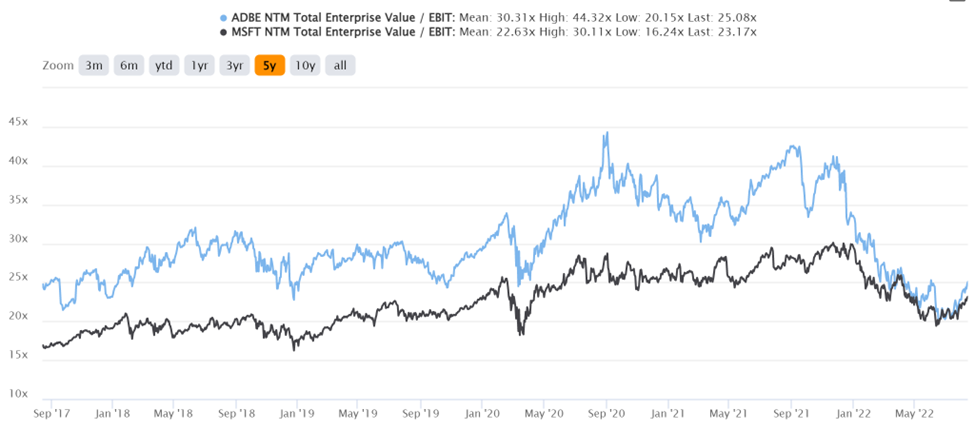

One thing that I noticed is Adobe has consistently traded at a premium to Microsoft in the last 5 years. The premium was really wide in 2020 and 2021 (EV/EBIT multiple of ~25x for MSFT vs ~40x for ADBE), but it has recently come down to trade much more closely with each other even though ADBE still trades at a slight premium. While ADBE’s EBIT grew at 31.2% CAGR over the last 5 years, MSFT’s EBIT grew at 25.1% CAGR. So, the premium is not without justification. But looking at the competitive dynamics, durability, and strength of ADBE’s vs MSFT’s moats, I would be far less enthusiastic to pay any premium for ADBE compared to MSFT.

Section 6: Final Words

There is always a lot to learn from studying a software company that has not only survived but absolutely dominated its industry for four decades. Studying Adobe’s journey for the first couple of decades reminded me that the path to such lofty success is hardly ever a straight line. This deep dive has also made me realize once again that outsized success in tech can be very, very difficult to predict. There is no way I would have assumed Adobe would reinvent itself after its deteriorating operating fundamentals in 1996-2002. Imagine how frustrating the investors must have been during that period and little did they realize Adobe would be showered with outlandish success in the next couple of decades. If I were studying Adobe in 2011, I would almost certainly seriously underestimate what their 2021 topline and bottom-line would be. I’m reiterating this to remind myself and the readers that 2030 is a long way from here. As a long-term investor, I must focus on the company’s long-term fundamentals and as you can see, yet we are awfully equipped to predict the long-term future of these businesses. Adobe’s moat in Digital Media is certainly strong, but that’s no secret. A thornier question is whether it will remain just as strong or weaken significantly by 2030. Your level of comfort in answering that question will perhaps largely dictate whether you want to own a piece of Adobe. Another important question is what the terminal economics in Digital Experience is. I have spoken with bulls who mentioned they believe Digital Experience's operating margins can be as high as 20-25%. I am a little skeptical but hope to have a bit more clarity after studying Salesforce.

Adobe Update (September, 2022) here (read section 6)

Adobe Update (October, 2022) here

Portfolio Discussion: Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up as my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.